Look at a wall. Any classroom, any office, any dusty library. You’ll likely see a continents and oceans map pinned up, looking all authoritative and final. But here is the thing: that map is basically a massive lie.

Not because of some conspiracy, but because of math. You can't peel an orange and lay the skin perfectly flat without tearing it. Mapmakers have been struggling with this "orange peel" problem for centuries, and honestly, we’ve just sort of accepted some weird distortions as gospel. We look at Greenland and think it’s the size of Africa. It isn't. Not even close. Africa is actually fourteen times larger.

Understanding the world requires unlearning the rectangular bias of the Mercator projection. It means looking at the 71% of our planet that is blue and realizing we often treat it like empty space when it’s actually the engine of our entire climate.

The Big Seven: More Than Just Shapes on a Page

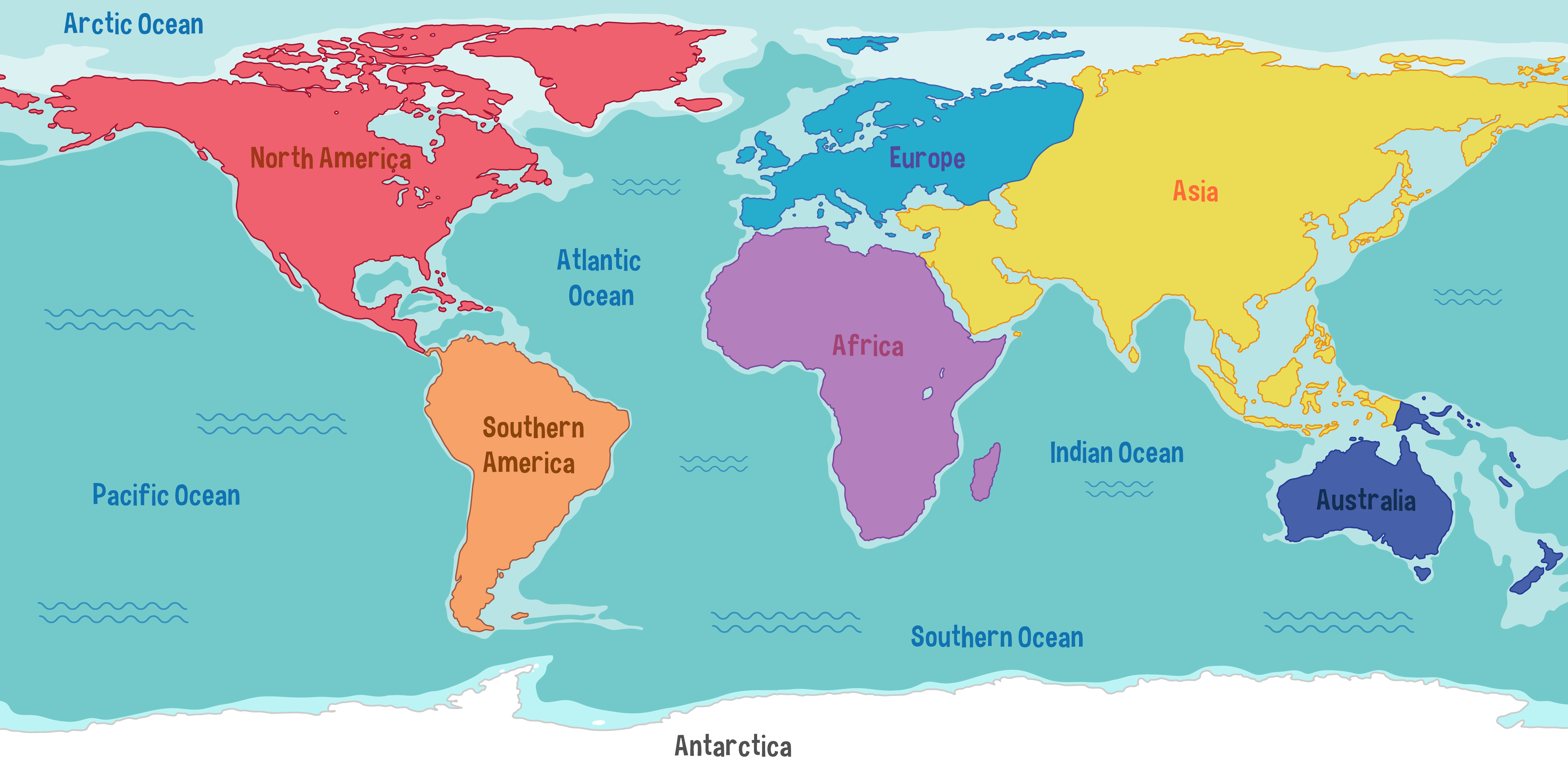

We’re taught there are seven continents. It feels like a solid, unshakeable fact. But if you grew up in Russia or parts of Europe, you might have learned there are six. If you’re a geologist, you might argue there are only two or three "true" tectonic masses.

Take Asia. It’s the undisputed heavyweight. It covers about 30% of Earth’s land area. When you look at a continents and oceans map, Asia is so massive it stretches from the freezing Arctic circles down to the tropical equator. It’s home to over 4.7 billion people. That’s a number so big it’s hard to wrap your head around. Basically, if you randomly picked a human being off the street, there’s a better than 50% chance they live in Asia.

Then you’ve got Africa. This is where maps usually fail us. Because of the way maps are flattened, Africa often looks "squashed." In reality, you could fit the United States, China, India, and most of Europe inside Africa’s borders and still have room for dessert. It contains the Nile, the world’s longest river, and the Sahara, a desert that is actually growing.

North America and South America are often lumped together in casual conversation, but they couldn't be more different. North America is home to the world’s largest island, Greenland—which, again, isn't as big as it looks on your screen. South America is dominated by the Amazon Basin. It’s the lungs of the planet. If you've ever seen a satellite view of the Amazon, the sheer density of green is staggering.

Antarctica is the one everyone forgets until they need to win at trivia. It’s a desert. Seriously. A polar desert. It holds about 70% of the world’s fresh water, but it’s all locked in ice. If it all melted? Say goodbye to Florida.

Europe is technically just a giant peninsula sticking off the side of Asia. We call it a continent for historical and cultural reasons, but geographically, it’s Eurasia. It’s densely packed, highly developed, and has more coastline per square mile than almost anywhere else.

Finally, there’s Australia. Or Oceania, depending on who you ask. It’s the only continent that is also its own country (mostly). It’s old. Geologically, it’s one of the most stable and ancient landmasses on the planet, which is why the wildlife there looks like it was designed by a committee on psychedelics.

The Five Oceans: Not Just "Water"

Most people can name the Atlantic and the Pacific. Some might remember the Indian. But the continents and oceans map has evolved. In 2021, the National Geographic Society officially recognized the Southern Ocean. That’s the cold, choppy water surrounding Antarctica.

The Pacific Ocean is the king. It’s larger than all the landmasses on Earth combined. Think about that for a second. You could take every continent, every island, every bit of dirt, and sink it into the Pacific, and you’d still have room to boat around. It contains the Mariana Trench, which is deeper than Mount Everest is tall. If you dropped Everest into the trench, there would still be over a mile of water above the peak.

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest. It’s getting bigger, too. Every year, the Mid-Atlantic Ridge pushes the Americas away from Europe and Africa by about an inch. It’s a slow-motion breakup. The Atlantic is crucial for the "Global Conveyor Belt"—the current system that keeps Europe from freezing solid in the winter.

The Indian Ocean is the warmest. It’s also a massive trade hub. A huge chunk of the world’s oil passes through these waters. It’s bounded by Africa, Asia, and Australia, making it a bit of a "closed" ocean compared to the others.

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest. It’s mostly covered by ice, but that’s changing fast. As the ice melts, new shipping routes are opening up, which is turning the Arctic into a bit of a geopolitical chessboard.

The Southern Ocean is unique because it’s defined by a current—the Antarctic Circumpolar Current—rather than landmasses. It’s where the cold, dense water of the south meets the warmer northern waters. It’s wild, it’s windy, and it’s vital for sequestering carbon.

Why Scale Matters (And Why Most Maps Fail)

If you use a standard continents and oceans map based on the Mercator projection, you are seeing a version of the world designed for 16th-century sailors. It’s great for navigation because straight lines represent constant compass bearings. But for understanding the actual size of things? It sucks.

- The Greenland Problem: On a Mercator map, Greenland looks roughly the same size as Africa. Africa is 11.7 million square miles. Greenland is 836,300 square miles.

- The Alaska-Brazil Comparison: Alaska looks like it could swallow Brazil. In reality, Brazil is five times larger than Alaska.

- The Center of the World: Most maps produced in the West put Europe and Africa in the center. But go to China, and you’ll find maps that center the Pacific. There is no "top" or "bottom" in space. We just decided North is up because of the people who made the first widely used globes.

To see the world accurately, you should look at the Gall-Peters projection or the Winkel Tripel projection. The Winkel Tripel is what National Geographic uses because it strikes the best balance between size and shape. It looks a bit "curvy" at the edges, but it’s much closer to reality.

The Hidden Continent: Zealandia

Here is a fun fact to pull out at dinner: there might actually be eight continents. In 2017, geologists confirmed the existence of Zealandia. It’s a massive landmass that is 94% underwater. New Zealand is just the highest peaks of this sunken continent.

It fits all the criteria for being a continent: it’s elevated above the surrounding ocean floor, it has distinct geology, and it’s much thicker than the oceanic crust. We just don't see it on most maps because, well, we can't see through two miles of water very easily. It’s a reminder that our continents and oceans map is just a snapshot of a changing planet.

Practical Ways to Use This Knowledge

Geography isn't just about memorizing names for a test. It’s about context. If you’re looking at a map for travel, business, or just to understand the news, keep these tips in mind.

📖 Related: July 23rd Zodiac: The Leo-Cancer Cusp is More Than Just a Vibe

Check the Projection

Always look at the bottom of a map to see which projection it uses. If it’s Mercator, take the sizes of countries near the poles with a huge grain of salt. If you’re trying to compare land mass, find an "Equal Area" map.

Follow the Currents

Don't just look at the blue space as empty. The oceans are the world's thermal regulator. When you see news about "El Niño," that's a direct result of temperature changes in the Pacific that affect weather in London and New York. The connection between the continents and oceans map and your local weather is absolute.

Think Three-Dimensionally

Remember that the world is a sphere. If you want to fly from San Francisco to Tokyo, the shortest route isn't a straight line across the map. It’s a curve that goes up toward Alaska. This is called a "Great Circle" route.

Acknowledge the Shifts

Earth is dynamic. Plate tectonics are constantly moving. Millions of years from now, the map will be unrecognizable. Africa is slowly splitting along the East African Rift. Eventually, a new ocean will form there. The map you see today is just one frame in a very long movie.

To really get a feel for the world, stop looking at flat maps for a while. Buy a globe. Or better yet, use digital tools like Google Earth that allow you to rotate the planet without the distortion of a flat plane. You’ll realize that the Pacific is even bigger than you thought, and that the "top" of the world is actually just a tiny, frozen ocean surrounded by massive landmasses.

👉 See also: How Many Days Till March 9th: The Countdown and Why This Date Hits Different

Understanding the true layout of our planet changes how you see everything from climate change to international trade. It makes the world feel both smaller and infinitely more complex. Don't let a 500-year-old navigation shortcut dictate how you perceive the home we all share. Look closer at the edges. That’s where the real story is.