Numbers are weird. Not just "math is hard" weird, but fundamentally broken once you get past a certain amount of zeros. You’ve probably seen a chart of million billion trillion floating around the internet, maybe in a textbook or a viral infographic about billionaire wealth. But here’s the thing: depending on where you grew up, those words might mean totally different things. It’s called the "Scale Problem," and if you’re doing international business or just trying to understand the national debt, it matters.

Ever tried to visualize a billion? Most people can’t.

If I gave you a million seconds, you’d be done in about 11 days. Easy. But if I gave you a billion seconds? You wouldn't finish for 31 years. That jump is massive. Now, try a trillion. A trillion seconds is roughly 31,700 years. We went from a long vacation to the entire history of human civilization just by adding a few more zeros to the chart of million billion trillion.

The Great Divide: Short Scale vs. Long Scale

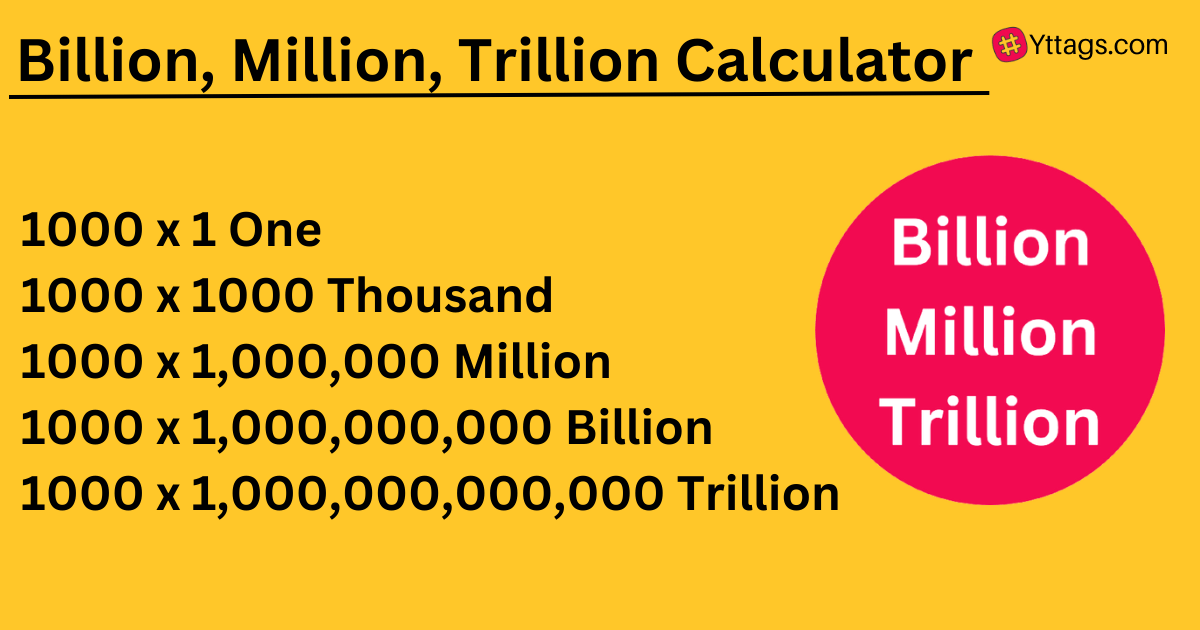

Most of us in the US, UK, and modern financial hubs use what’s called the "Short Scale." In this system, every new "illion" name is 1,000 times larger than the one before it. A billion is a thousand millions ($10^9$). A trillion is a thousand billions ($10^{12}$). Simple, right?

Well, not for much of Continental Europe or Latin America.

They often use the "Long Scale." In that system, a billion is actually a million millions ($10^{12}$). What we call a trillion, they might call a billion. It sounds like a pedantic trivia point until you realize that a business contract written in one country might mean something a thousand times larger in another. Imagine the legal nightmare. Historically, the UK actually used the long scale until the 1970s when Harold Wilson’s government officially swapped to the US version to keep things consistent in global finance.

Basically, your chart of million billion trillion needs a "Location" header to be factually accurate.

Visualizing the Zeros

Let's look at the actual progression. If you’re building a reference for yourself, you need to see the "steps" of 1,000.

A Million is 1,000,000. Six zeros. Think of it as a small pile of cash that fits in a briefcase.

A Billion is 1,000,000,000. Nine zeros. This is where it gets heavy. If you had a billion dollars in $100 bills, it would weigh about 10 tons. You’d need a literal semi-truck to move it.

A Trillion is 1,000,000,000,000. Twelve zeros. This is the realm of national GDPs and the total value of companies like Apple or Microsoft. If you spent a million dollars every single day since the day Jesus was born, you still wouldn't have spent a trillion dollars today. Not even close. You’d be less than halfway there.

The list keeps going, though we rarely use these names in daily life:

- Quadrillion (15 zeros)

- Quintillion (18 zeros)

- Sextillion (21 zeros)

- Septillion (24 zeros)

In the scientific community, they usually ditch the names and go for "Scientific Notation." It’s just cleaner. Writing $10^{24}$ is way easier than trying to remember if "Septillion" comes before or after "Sextillion." Honestly, once you hit a quadrillion, the human brain stops being able to distinguish the scale anyway. It all just becomes "unthinkably huge."

Why This Math Actually Hits Your Wallet

You might think, "I'm never going to have a trillion dollars, so why do I care about a chart of million billion trillion?"

Inflation.

👉 See also: Pillars of Wall Street: Why This Training Still Matters for Breaking Into High Finance

In the 1920s, being a "Millionaire" was the pinnacle of human wealth. Today, in cities like San Francisco or New York, a million dollars buys you a nice two-bedroom condo and maybe a parking spot. It’s still a lot of money, but it’s no longer "never work again" money for a 30-year-old.

We are seeing the "Billionaire" become the new standard for extreme influence. Policy debates now revolve around "Trillion-dollar infrastructure bills." When we lose sight of the scale, we lose the ability to judge whether spending is efficient or wasteful. If a government wastes a million dollars, it’s a rounding error. If they waste a trillion, it’s a generational catastrophe. Without a firm grasp of this chart, those headlines just blur into "big numbers."

Misconceptions That Mess People Up

One big mistake people make is thinking that "zillions" or "gazillions" are real numbers. They aren't. They’re just placeholders for "I don't know how to count this high."

Another one? The "M" vs "MM" confusion in finance. In some accounting circles, "M" stands for a thousand (from the Latin mille) and "MM" stands for a million (a thousand thousands). But in social media and general use, "M" means million and "K" means thousand. If you're reading a financial statement and see "10MM," don't assume it's a typo for "10 Million." It’s actually a very old-school way of saying exactly that.

The Indian Numbering System

We can't talk about a chart of million billion trillion without mentioning the Indian system, which is used by over a billion people. They don't jump by thousands after the first thousand. They use Lakhs and Crores.

- 1 Lakh is 100,000 (one hundred thousand).

- 1 Crore is 10,000,000 (ten million).

If you’re watching a Bollywood movie or reading the news in Delhi, you’ll see "10,00,000" instead of "1,000,000." The comma placement is different. It’s not a typo. It’s a different way of grouping the world. This is why global financial software has to be incredibly robust—one comma in the wrong place and you’ve just sent someone 10 times more money than you intended.

Putting the Scale to Work

If you're trying to explain these numbers to kids, or maybe just trying to wrap your own head around the federal budget, use time or distance.

Distance is great. A million inches is about 15 miles. A billion inches? That’s nearly 16,000 miles—more than halfway around the Earth. A trillion inches takes you past the moon, around it, and back.

It's also helpful for understanding data. We used to talk about Megabytes (millions). Then Gigabytes (billions). Now we buy hard drives in Terabytes (trillions). The next step is Petabytes. We are living through a period where the average person is interacting with trillions of bits of data every single day. We are all technically "Trillionaires" of data, even if our bank accounts don't reflect it.

Your Actionable Summary for Large Numbers

To keep your head straight when looking at a chart of million billion trillion, follow these three rules:

📖 Related: Is Aunt Jemima back on bottles? The Truth Behind the Pearl Milling Company Rebrand

- Verify the Scale: If you are dealing with an international client (especially in Europe or South America), clarify if "billion" means $10^9$ or $10^{12}$. It sounds awkward to ask, but it's better than a multi-billion dollar misunderstanding.

- Use the "Rule of Three": Every three zeros is a new name in the short scale. 3 = thousand, 6 = million, 9 = billion, 12 = trillion. If you can count the comma groups, you can name the number.

- Contextualize with Time: Always convert a large number to seconds if you want to feel the weight of it. It’s the only way to shock the brain into realizing how much bigger a billion is than a million.

The best way to master this is to stop looking at the names and start looking at the groups of zeros. Names change by language and culture, but the math is universal. Whether you call it a milliard or a billion, a nine-zero number is always going to be a thousand times bigger than a six-zero one.

Keep a simple cheat sheet in your notes:

- Million: 6 zeros (10^6)

- Billion: 9 zeros (10^9)

- Trillion: 12 zeros (10^{12})

- Quadrillion: 15 zeros (10^{15})

Next time you see a headline about a "trillion-dollar" valuation, remember the seconds. 31,700 years. That’s the kind of scale we’re actually dealing with in the modern economy. It’s not just a big number; it’s an astronomical one.