You’ve seen them. Those viral photos of a butterfly face under microscope that look less like a delicate garden visitor and more like a rejected extra from a 1980s sci-fi horror flick. It’s a weird bait-and-switch. We grow up thinking butterflies are the "pretty" insects—the ones we actually like having land on us—but zoom in enough and the illusion totally breaks.

The truth is, a butterfly's face is a masterpiece of specialized engineering, but it's also incredibly alien.

When you get up close, the first thing that hits you isn't the color. It’s the texture. It’s hairy. Like, surprisingly hairy. What we think of as smooth skin or simple "bug shell" is actually covered in sensory hairs and scales that serve very specific biological purposes. If you’re looking at a butterfly face under microscope, you aren't just looking at a bug; you're looking at a high-tech sensory array designed for one thing: finding sugar.

The multi-lens madness of compound eyes

The eyes are usually what freak people out first. Most insects have compound eyes, but butterflies take it to a different level. Under a scanning electron microscope (SEM), those big bulging orbs turn into a grid of thousands of tiny hexagonal lenses called ommatidia.

It’s literally a mosaic.

A butterfly doesn't see a single clear image like we do. Instead, each of those thousands of lenses captures a tiny piece of the world. Their brains then stitch it all together. It's low resolution compared to our vision, but it's incredible at detecting motion. Try sneaking up on one. You can't. They see you coming from almost a 360-degree angle because of how those eyes wrap around the sides of the head.

But here’s the kicker: they see colors we literally cannot imagine. While we’re stuck with red, green, and blue, many butterflies see ultraviolet (UV) light. Under the microscope, you might see "eye caps" or specialized structures that help filter this light. This UV vision allows them to see "nectar guides" on flowers—basically landing lights that are invisible to humans but look like a glowing bullseye to a butterfly.

That giant "tongue" is actually two pipes

If you look at the butterfly face under microscope near the bottom of the head, you’ll see the proboscis. Most people call it a tongue. It’s not. It’s actually two separate semi-cylindrical tubes that are joined together by tiny interlocking hooks. Think of it like a biological zipper.

When a butterfly emerges from its chrysalis, the first thing it has to do is "zip" its mouth together. If it fails, it starves.

Under high magnification, the proboscis looks like a coiled spring or a heavy-duty garden hose. It’s covered in "sensilla," which are tiny hair-like structures that can actually "taste" things. Imagine if your tongue was six feet long and you could taste a cupcake just by tapping it with the tip of your shoe. That’s basically the life of a butterfly.

👉 See also: The San Onofre Nuclear Plant Mess: What’s Actually Happening Right Now

They don't just use the proboscis for nectar, either. You’ll often see them around muddy puddles—a behavior called "puddling." They’re sucking up minerals and salts that they can't get from flowers. Under the microscope, you can sometimes see the wear and tear on the proboscis from these minerals, showing that even a butterfly's life is a bit of a grind.

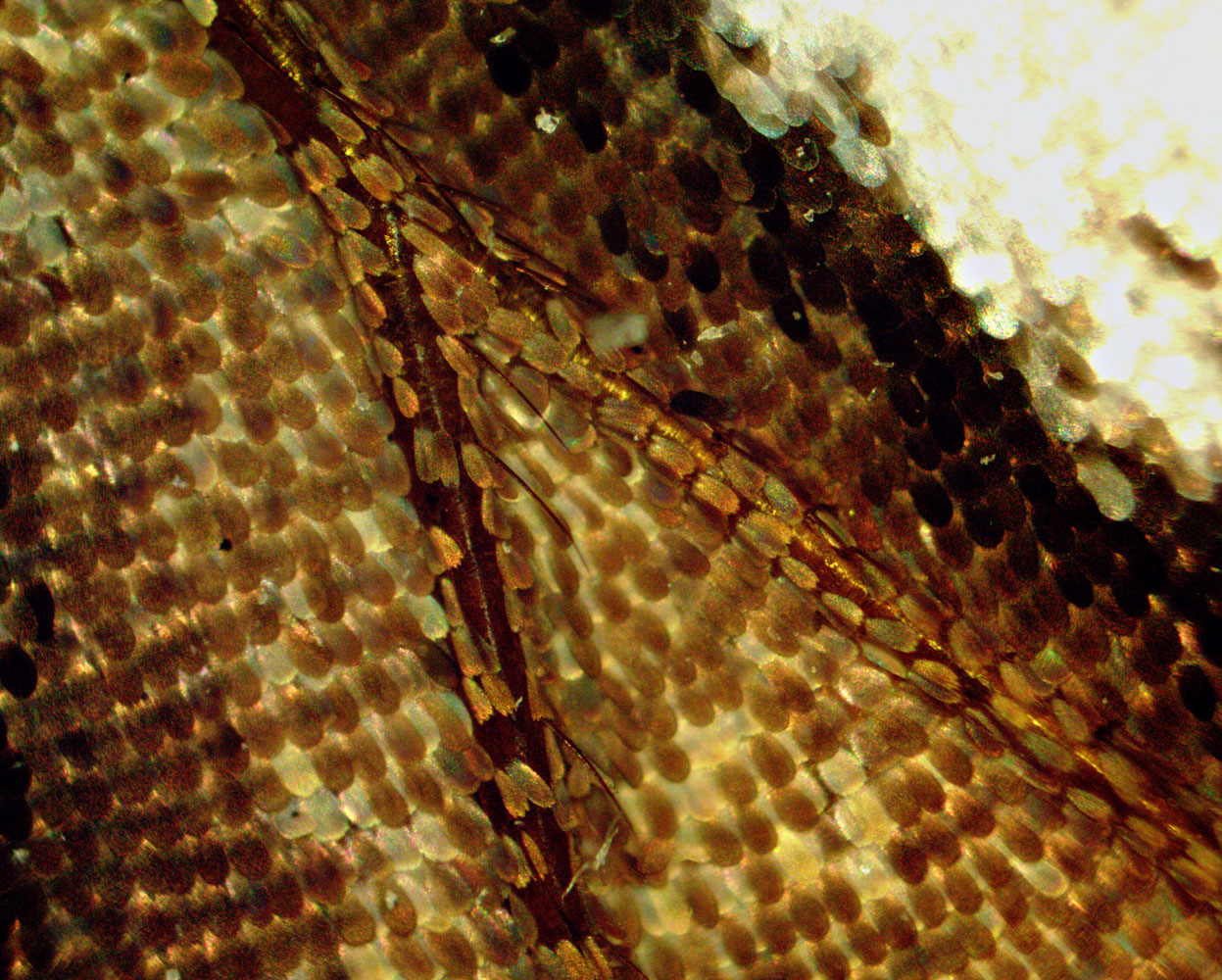

Scales are the secret to the shimmer

The "powder" that comes off on your fingers if you accidentally touch a butterfly? Those are scales. This is what separates the order Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths) from everything else. The name literally means "scale wing," but the scales cover the face too.

At 1000x magnification, these scales look like shingles on a roof. Or maybe rows of tiny, flat feathers.

Why the colors look different up close

There are two ways butterflies get their color:

- Pigment: Actual chemical colors (whites, oranges, browns).

- Structural Color: This is the cool part. The scales have microscopic ridges that trap and bounce light.

When you look at a Blue Morpho butterfly face under microscope, you aren't seeing blue "paint." You're seeing physics. The scales are shaped in a way that cancels out all light except for the blue wavelength. If you were to pour alcohol on the scales, the blue would disappear because you’ve changed how the light bends. Once the alcohol dries, the blue comes right back. It’s a trick of the light that’s been perfected over millions of years.

The "Hairy" truth about palps

See those two fuzzy things sticking out next to the proboscis? Those are the labial palps. Honestly, they look like a mustache gone wrong.

These are densely packed with scent receptors. While the antennae do the heavy lifting for long-distance smelling, the palps are for close-range work. They help the butterfly "sense" the flower once they've landed. Under the microscope, these palps are thick with "setae" (stiff hairs). They protect the eyes and the proboscis from pollen and debris.

They also act as a sort of "sheath" for the proboscis when it's coiled up. It’s a very compact, efficient storage system. Evolution doesn't waste space. Every single hair you see under that lens has a job, whether it's detecting wind speed, sensing humidity, or tasting the air for predators.

Why we find it so unsettling

There’s a psychological reason why a butterfly face under microscope feels so jarring. It’s the "Uncanny Valley" of the insect world. We associate butterflies with grace and beauty. When the microscope reveals the "monster" underneath—the jagged mandibles, the bristly hairs, the repetitive geometric eyes—it creates a sense of cognitive dissonance.

Biologist and photographer Levon Biss has spent years documenting insects in this way. His work shows that insects aren't "gross"; they’re just incredibly complex. When you see a butterfly at 5x or 10x magnification, it still looks like a butterfly. At 100x, it starts looking like a machine. At 1000x, it looks like another planet.

It reminds us that our human perspective is just one way of seeing the world. To a butterfly, a "face" isn't for expressions or smiles. It's a cockpit. It’s a centralized hub for data processing. Every millisecond, the butterfly is processing UV light patterns, wind resistance on its palps, and chemical signals from the flowers below.

How to see it for yourself

You don't need a $50,000 electron microscope to appreciate this. A decent digital USB microscope or even a "macro" lens for your smartphone can get you close enough to see the scale structure and the coiling of the proboscis.

If you want to dive deeper into the world of micro-photography, here is how you should actually approach it.

Find a "found" specimen. Don't go out and kill butterflies for a hobby. Look on windowsills or in gardens for butterflies that have naturally reached the end of their life cycle. Their bodies are remarkably preserved.

Lighting is everything. Because butterfly scales are so reflective, direct flash will wash everything out. Use "diffused" light. A piece of tissue paper over a desk lamp works wonders. It softens the shadows and lets the structural colors pop.

Focus stacking is the pro secret. If you wonder why professional photos of a butterfly face under microscope look so sharp, it's because they aren't just one photo. They take 50 or 100 photos at slightly different focus points and "stack" them using software like Helicon Focus. This gives you that "deep" focus where the eyes and the antennae are both perfectly crisp.

Look for the "Scent Patches." On some species, you can find specialized scales that release pheromones to attract mates. These look different from the "shingle" scales. They're often more plume-like or clustered in specific areas of the head and wings.

The next time you see a Monarch or a Painted Lady fluttering by, remember the "monster" underneath. It's not actually scary. It's just a level of detail that our eyes weren't built to see. The "hair" is a sensor, the "eyes" are a computer, and the "face" is a masterpiece of natural engineering that makes our best technology look like a child's toy.

Explore the world of macro-photography by starting with common garden finds. You can find high-quality macro clip-on lenses for under $30 that will turn your phone into a gateway to this microscopic world. Once you see the individual scales on a wing or the hexagons in an eye, you'll never look at a "pretty" butterfly the same way again. It's way more interesting than just a colorful bug.