Ever stood in a sterile hospital hallway and wondered why the nurses are so obsessed with checking your wristband five times before a transfusion? It’s not just red tape. Honestly, it’s because your immune system is basically a high-security bouncer at an exclusive club. If the wrong blood type tries to get in, that bouncer doesn't just ask them to leave—he starts a riot. This is where the blood type donor and recipient chart comes into play, and it’s way more than a simple grid you memorized in high school biology. It’s a literal map of biological compatibility that keeps you from having a catastrophic hemolytic reaction.

Blood is weird.

We think of it as just "red stuff," but it’s a complex soup of antigens and antibodies. If you’re Type A, your red cells have A-shaped proteins on them. Your body sees these as "self." But it also carries "Anti-B" antibodies that are constantly on the lookout for Type B invaders. If a doctor accidentally gives you Type B blood, your antibodies will latch onto those new cells and literally pop them. It’s messy, it’s dangerous, and it’s why understanding who can give to whom is the backbone of modern emergency medicine.

The ABO System: More Than Just Letters

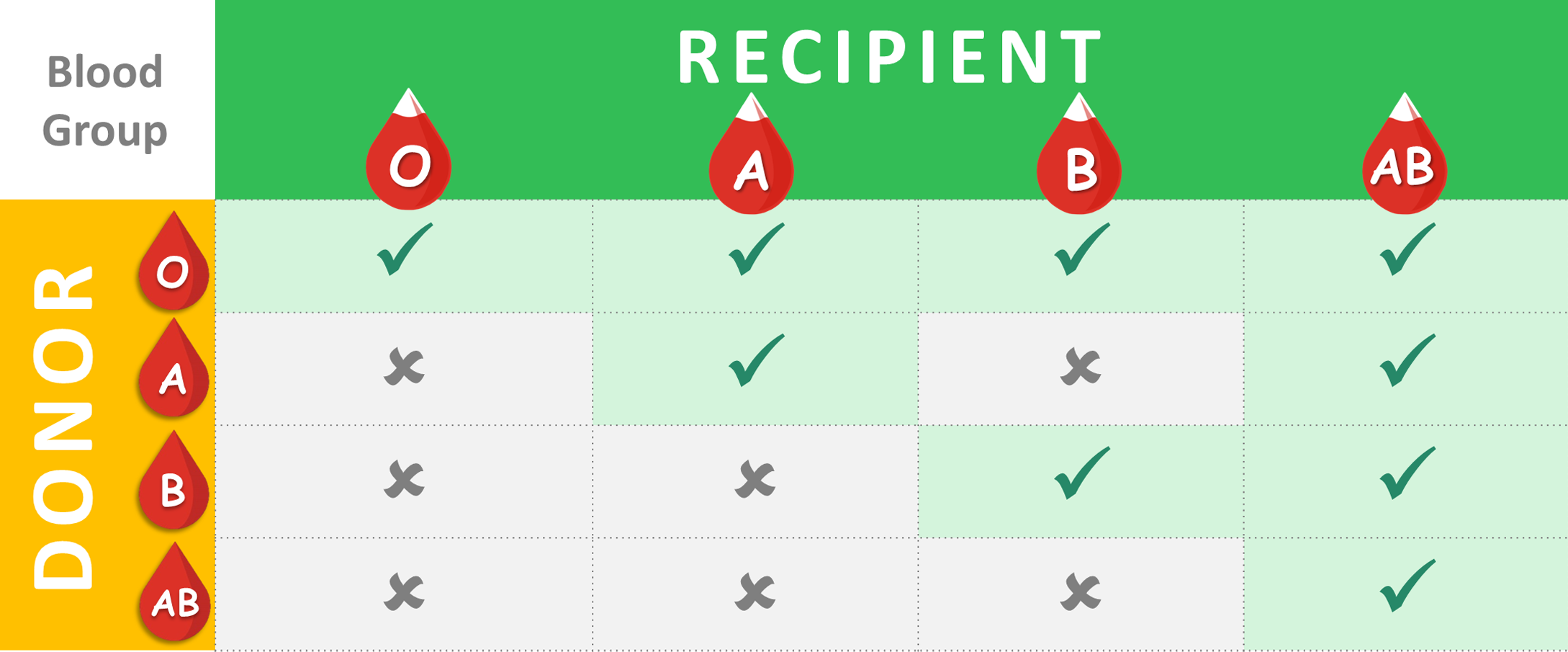

Most people think there are just four blood types, but that’s a bit of a simplification. You've got A, B, AB, and O. These are determined by the presence or absence of specific antigens. Type A has the A antigen. Type B has the B antigen. AB is the lucky one with both, and Type O is the "naked" one with neither. This is the foundation of any blood type donor and recipient chart.

Think about Type O for a second. Because it lacks A or B antigens, the recipient’s immune system doesn't see anything to attack. That makes Type O negative the "Universal Donor." In a trauma bay where a patient is bleeding out and there’s no time to test their blood, the doctors reach for the O-neg. It’s the "break glass in case of emergency" blood. But here is the kicker: Type O people can only receive Type O blood. They are the ultimate givers but the most restricted receivers. It’s a bit of a biological irony.

On the flip side, we have Type AB positive. These people are the "Universal Recipients." Since their blood already recognizes both A and B antigens, and they have the Rh factor, they can take blood from literally anyone. If you're AB+, you’re basically the human equivalent of a multi-tool. You can accept A, B, AB, or O without your body throwing a fit. However, your blood is only useful to other AB+ folks.

The Rh Factor: That Pesky Plus or Minus

You’ve probably noticed that people don't just say "I'm Type A." They say "A positive" or "O negative." That "positive" or "negative" refers to the Rhesus (Rh) factor, specifically the D antigen. It was named after the Rhesus macaque monkeys where it was first discovered, which is a bit of a fun trivia fact for your next dinner party.

✨ Don't miss: Horizon Treadmill 7.0 AT: What Most People Get Wrong

If you have the Rh protein, you're positive. If you don't, you're negative. This adds a whole other layer to the blood type donor and recipient chart. A positive person can usually receive both positive and negative blood of their type. But a negative person? They generally shouldn't receive positive blood. If an Rh-negative person is exposed to Rh-positive blood, their body creates antibodies against it. This might not be a huge deal the first time, but the next time it happens, the immune system is primed and ready to attack. This is especially critical in pregnancy, a condition known as Rh incompatibility, where an Rh-negative mother’s body might attack the blood cells of an Rh-positive fetus. Thankfully, we have RhoGAM shots for that now, which is a massive win for modern science.

Breaking Down the Donor-Recipient Logic

Let's get into the weeds of how these interactions actually look in practice.

If you are Type A+, you can give to other A+ people and AB+ people. You can receive from A+, A-, O+, and O-. It’s a decent range of options.

Type A- is a bit rarer. You can give to A-, A+, AB-, and AB+. But you can only receive from A- and O-.

Type B+ follows a similar logic. You can give to B+ and AB+, and receive from B+, B-, O+, and O-.

Type B- can give to B-, B+, AB-, and AB+, but they are limited to receiving from B- and O-.

🔗 Read more: How to Treat Uneven Skin Tone Without Wasting a Fortune on TikTok Trends

Then we have the AB+ "super-receivers" we mentioned earlier. They can give only to other AB+ people, but they can take from everyone. AB- is the "Universal Plasma Donor," which is a nuance many people miss. While their red blood cells aren't universally compatible, their plasma is, because it lacks both Anti-A and Anti-B antibodies.

Finally, Type O+. This is the most common blood type in the world. About 37% to 38% of the population has it. They can give to A+, B+, AB+, and O+. They can receive from O+ and O-.

And the rarest of the rare in terms of emergency utility: Type O-. Only about 7% of people have it. They can give to every single person on this list. But they can only receive from other O- donors. This is why blood banks are constantly calling O- donors. They are the backbone of the entire transfusion system.

Why the "Universal" Labels Can Be Misleading

I should probably mention that "universal" is a bit of a "kinda-sorta" term. In a perfect world, doctors always prefer an identical match. Giving O-negative to an A-positive person is a life-saving measure, but it's not the first choice. Why? Because blood is more than just ABO and Rh. There are over 300 minor antigens, like Kell, Kidd, and Duffy.

Most of the time, these don't cause issues. But for people who need frequent transfusions—like those with Sickle Cell Disease or Thalassemia—these minor antigens start to matter a lot. Their bodies can become "sensitized" to these tiny differences, making it harder and harder to find a match. This is why donor diversity is so huge. A patient with Sickle Cell often needs blood from a donor with a similar ethnic background to ensure the best possible match of those minor antigens. It’s not just about the big letters on the blood type donor and recipient chart; it’s about the subtle biological nuances that make us who we are.

The Logistics of Giving: What Actually Happens?

When you donate, your blood doesn't just go straight into someone else's arm. It gets spun down in a centrifuge. You get red cells, plasma, and platelets. This is why one donation can "save three lives."

💡 You might also like: My eye keeps twitching for days: When to ignore it and when to actually worry

The red cells are what we usually talk about regarding the blood type donor and recipient chart. They carry oxygen. Plasma, the yellowish liquid, carries proteins and clotting factors. Platelets help stop bleeding. Interestingly, the compatibility rules for plasma are the exact opposite of red cells. For plasma, AB is the universal donor because it has no antibodies. O is the universal recipient for plasma. It’s like a mirror image of the red cell rules.

Real-World Impact: The "Golden Blood" Mystery

If you think O-negative is rare, let's talk about Rh-null. This is often called "Golden Blood" because it lacks all 61 possible antigens in the Rh system. There are fewer than 50 people in the entire world known to have it.

For these individuals, a blood type donor and recipient chart is basically a map of "No." They can give to anyone with a rare Rh-system blood type, but they can only receive from other Rh-null people. If you have Golden Blood, you're encouraged to donate for yourself—essentially banking your own blood in case you ever need it—because finding a random donor is nearly impossible. It highlights how much we take for granted when we walk into a hospital and expect a bag of blood to be ready for us.

The Future of Transfusions

We’re getting better at this. Researchers are currently working on "enzymatic conversion," which is basically using enzymes to "strip" the antigens off Type A or Type B blood to turn it into Type O. Imagine a world where we don't have to worry about the blood type donor and recipient chart because we can just make any blood universal. We aren't quite there for wide clinical use yet, but the trials are promising.

Until then, we rely on the generosity of human beings. Blood cannot be manufactured in a lab. Every drop on that chart comes from a person sitting in a chair, squeezing a stress ball, and eating a post-donation cookie.

Practical Steps for You

So, what do you actually do with this information?

- Find out your type. If you don't know it, look at your birth records or ask your doctor. Better yet, go donate. They’ll tell you for free.

- Understand your utility. If you are O-negative, you are a literal hero in waiting. If you are AB+, your plasma and platelets are gold.

- Register for emergencies. Hospitals often have "walking blood banks" in rural areas or specialized registries for rare types.

- Don't ignore the minor antigens. If you have a chronic condition requiring transfusions, talk to your hematologist about "phenotype matching" rather than just basic ABO matching.

- Keep your "Blood Card" handy. Many people keep a card in their wallet or have it listed in their phone’s Medical ID. In a crash, this saves precious minutes for the trauma team.

The blood type donor and recipient chart isn't just a clinical document. It’s a testament to how interconnected we are. Your "type" might be exactly what a stranger three towns over needs to survive a surgery or an accident. It’s a simple system, but it’s the thin red line between a successful recovery and a fatal mistake. Check your type, know your match, and if you're able, get out there and donate. It’s the most basic way to be a part of the human safety net.