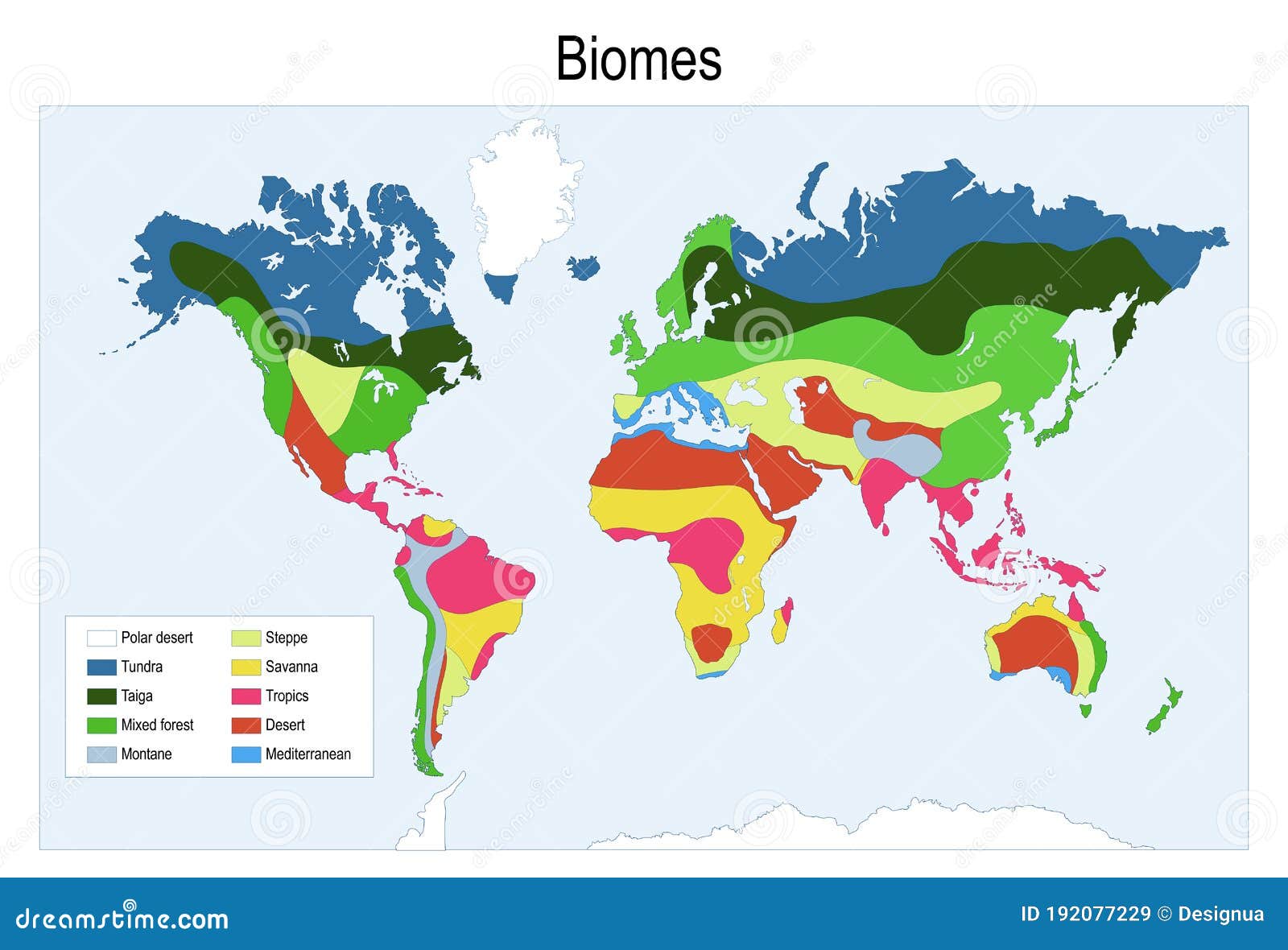

Walk into any middle school science classroom and you’ll see it. A bright, color-coded poster hanging on the wall showing the biomes of United States map. It looks clean. It looks simple. Green for forests, yellow for deserts, maybe a splash of purple for the alpine heights.

But nature doesn't actually work in straight lines or tidy boxes.

Honestly, those maps are kinda lying to you. They treat the transition from a Great Plains grassland to a Rocky Mountain forest like a border crossing where you show your passport. In reality, it’s a messy, blurry, chaotic "ecotone" where plants and animals are constantly fighting for a foothold. If you really want to understand the American landscape, you have to look past the primary colors. You have to see the struggle.

The Massive Scale of the Biomes of United States Map

The U.S. is huge. Obviously.

Because the country spans from the subtropics of Florida to the arctic gates of Alaska, it contains almost every major biome type on Earth. We are talking about a massive range of temperature and precipitation. This variety is what makes a biomes of United States map so complex to draw. If you look at the work of Robert Bailey, a legendary geographer for the U.S. Forest Service, he didn't just see "forest." He saw ecoregions layered like an onion.

He broke things down by climate, then landform, then vegetation.

🔗 Read more: Why the 2016 Toyota Tacoma TRD Sport Still Costs So Much

Why the 100th Meridian Changes Everything

If you take a pen and draw a vertical line right down the center of a U.S. map—roughly along the 100th meridian—you've just found the most important ecological divide in the country. To the east, you have a surplus of water. To the west, you have a deficit.

East of this line, the biomes of United States map is dominated by the Temperate Broadleaf Deciduous Forest. This is the classic American woods. Think oak, hickory, and maple trees that drop their leaves in the winter to survive the cold. It’s lush. It’s humid. It’s why Virginia looks nothing like Nevada.

West of that line? Everything changes. The shadows of the Rocky Mountains create rain shadows that suck the moisture out of the air. This is where the Great Plains begin, transition into shortgrass prairies, and eventually tumble into the true deserts of the Southwest.

The Temperate Rainforest: An Overlooked Giant

Most people think of rainforests and immediately picture the Amazon. They think of monkeys and macaws. But the biomes of United States map features a massive temperate rainforest that hugs the Pacific Northwest coast.

It’s different.

Instead of heat, you get "cool" moisture. It’s a land of giants—Sitka spruce, Western redcedar, and the iconic Douglas fir. These trees can grow over 250 feet tall because it basically never stops drizzling. This biome is a carbon-sequestering powerhouse. According to data from the Ecotrust organization, these forests store more carbon per acre than almost any other terrestrial ecosystem on the planet.

But here’s the kicker: it's disappearing. Or rather, it's being fragmented. When you look at a map, it looks like a solid block of green. On the ground? It's a patchwork of old growth, second-growth timber lands, and suburban sprawl. A map tells you what should be there, not necessarily what is actually left.

The Desert South: More Than Just Sand

People get the desert wrong. All the time.

They think it’s a wasteland. Actually, the Sonoran Desert in Arizona is one of the most biodiverse places in North America. When you look at a biomes of United States map, the Southwest is often colored a sandy tan. But that tan covers three very different worlds: the Mojave, the Sonoran, and the Chihuahuan.

- The Mojave: This is the high desert. It’s home to the Joshua Tree, which isn't even a tree—it’s a yucca. It’s dry, windy, and harsh.

- The Sonoran: This is the "lush" desert. It gets two rainy seasons. Because of that, you get the Saguaro cactus, those tall, multi-armed giants that look like they’re waving at you.

- The Chihuahuan: This is a shrub desert. It’s higher in elevation and dominated by creosote bushes and agave.

If you’re hiking in the Southwest, you’ll notice that as you go up in elevation, the biome shifts. You can start in a desert scrub and end up in a Ponderosa pine forest in a single afternoon. This is called "Vertical Zonation." It makes a 2D biomes of United States map look incredibly 3D if you know what to look for.

The Grasslands: The Forgotten Middle

The Great Plains are the "Big Empty" to many travelers. But biologically, they are a battlefield.

🔗 Read more: 1 8 cup equals how many teaspoons: The Simple Math for Every Kitchen

Historically, this biome was maintained by two things: fire and bison. Without regular fires, the forests of the East would have marched westward and swallowed the plains. The grasses here are tough. They have massive root systems—sometimes six feet deep—that allow them to survive drought and grazing.

There are three main "flavors" of prairie on the biomes of United States map:

- Tallgrass Prairie: The eastern edge. Lush, 8-foot-tall bluestem grass. Almost all of it has been converted to corn and soy.

- Mixed-grass Prairie: The middle ground.

- Shortgrass Prairie: The western edge. Think buffalo grass. It's shorter, hardier, and handles the dry air near the Rockies.

Moving Toward the Tundra

You can't talk about a biomes of United States map without mentioning Alaska. It’s the only place in the country where you find the Tundra.

It’s a world of permafrost. The ground stays frozen year-round just a few inches below the surface. Trees can’t grow because their roots hit a literal wall of ice. Instead, you get mosses, lichens, and tiny shrubs. It's a "cold desert" in many ways. It receives very little actual precipitation, but because it’s so cold, the water doesn’t evaporate. It just sits there, creating bogs and mosquitoes that could carry away a small dog.

The Problem with Static Maps

Climate change is making the biomes of United States map look like it was drawn in disappearing ink.

The "USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map" was recently updated, and you can see the shift. Heat zones are moving north. Trees that used to thrive in Georgia are struggling, while species typically found in the Carolinas are starting to migrate upward.

Biomes aren't permanent.

They are snapshots of a climate in a specific moment. If the West continues to get drier and the East gets stormier, those colors on your map are going to start bleeding into each other. We're seeing "savannification" in parts of the Amazon, and in the U.S., we are seeing the "desertification" of the Great Basin.

🔗 Read more: Old Farmhouse Living Room Ideas That Actually Feel Authentic (And Not Like a Set)

How to Actually Use This Info

If you’re looking at a biomes of United States map for a school project, a road trip, or just because you’re a nerd for geography, don't just look at the colors.

Look at the rivers. Look at the mountain ranges.

Biomes follow the water and the wind. If you want to see these transitions in real life, drive from Denver, Colorado, to St. Louis, Missouri. You will watch the world turn from brown to yellow to light green to deep, dark forest green. You’ll see the trees get taller and the air get heavier with humidity.

Actionable Steps for the Amateur Naturalist

- Download an Ecoregion App: Use tools like iNaturalist to see what plants are actually growing in your "biome." You might find that your backyard is a micro-climate that doesn't match the map at all.

- Check the 100th Meridian: If you live near it, visit a local state park and look for "indicator species." Are you seeing more cacti or more oaks?

- Support Local Land Trusts: Biomes only stay healthy if they are connected. Fragmented biomes lead to species loss.

- Observe the "Edge Effect": Go to the place where a forest meets a field. That’s where the most action happens. That’s where the deer, hawks, and foxes hang out.

The biomes of United States map is a great starting point, but it's just the table of contents. To get the whole story, you have to get out there and smell the pine needles or feel the dry desert wind for yourself. Nature doesn't care about our lines on a map; it only cares about where it can find a drink of water and enough sun to keep going.