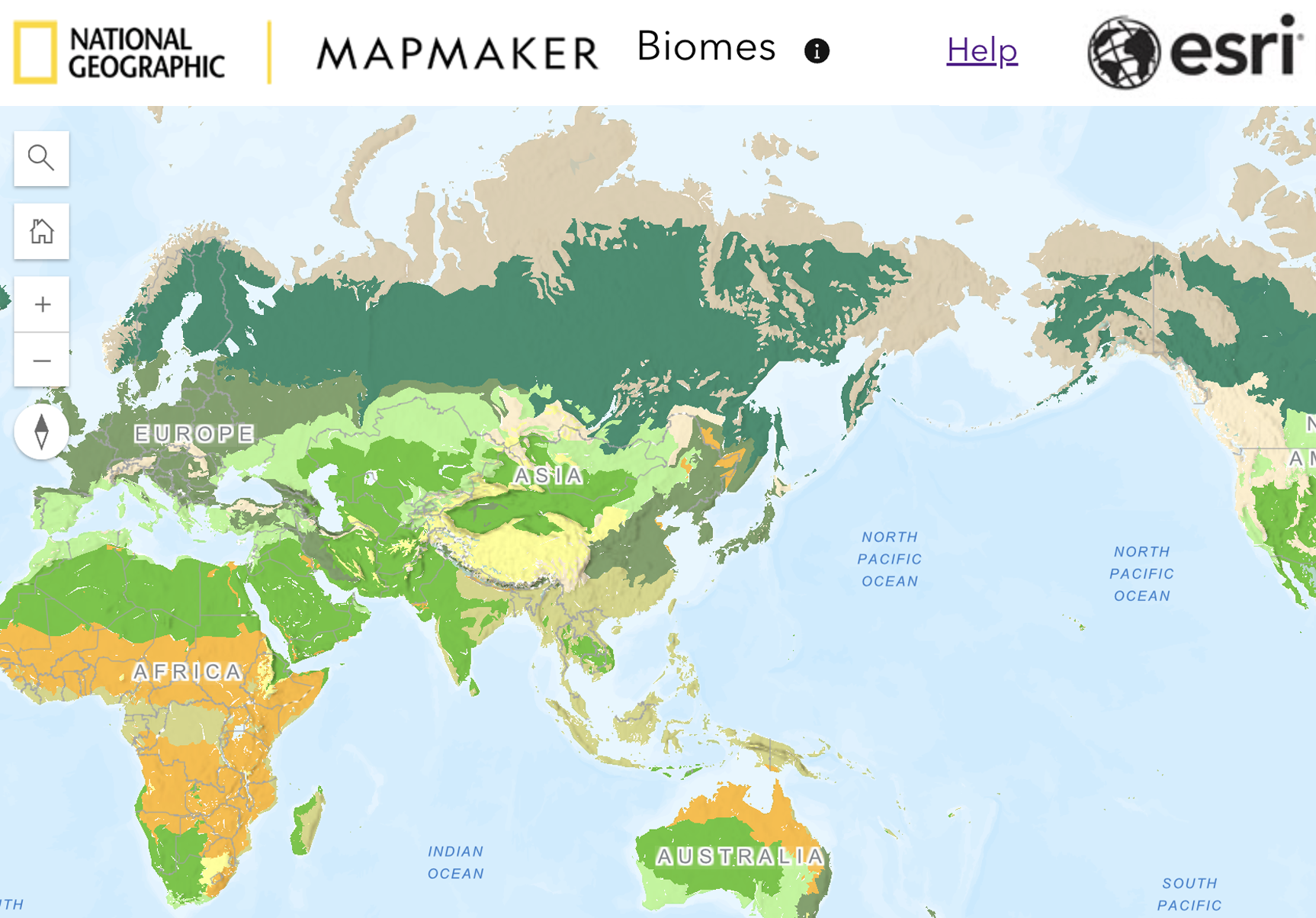

Africa is massive. You probably know that already, but seeing a biome map of Africa spread out across a screen or a textbook page doesn't quite prepare you for the reality of standing in the middle of the Okavango Delta or watching the red dunes of the Namib bleed into the Atlantic. Most people look at these maps and see big, clean blocks of color—green for rainforest, yellow for desert, orange for savanna. It looks simple. It looks settled. Honestly, though? It’s a mess. A beautiful, shifting, ecological mess that defies the neat lines cartographers love to draw.

When you dive into the geography of this continent, you’re looking at more than 30 million square kilometers. That is a lot of ground to cover. If you tried to drive from the Mediterranean coast down to the Cape of Good Hope, you’d cross roughly eight distinct major biomes, though scientists like those at the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) often break these down into hundreds of smaller ecoregions. The map is alive. It’s changing as we speak because of shifting rainfall patterns and human encroachment.

Understanding the biome map of Africa isn't just an academic exercise for geography nerds. It’s the blueprint for how life survives in some of the most extreme conditions on Earth. From the afro-alpine zones that get frost in the morning to the sweltering humid jungles of the Congo Basin, the diversity is staggering.

The Big Green Heart: The Tropical Rainforest

Everyone looks at the center of the map first. That’s the Congo Basin. It’s the second-largest tropical rainforest on the planet, trailing only the Amazon. But here’s the thing people get wrong: it isn’t just one giant, uniform wall of broccoli-looking trees.

It's layered. You’ve got the Guinean Forests of West Africa, which are critically fragmented now, and then the massive Congolian forests. This biome stays wet almost all year. We’re talking over 2,000 mm of rain annually in some spots. If you’re looking at a biome map of Africa, this is the deep, dark green. It’s the home of the lowland gorilla and the okapi—that weird "forest giraffe" that looks like a glitch in the Matrix.

The soil here is surprisingly poor. That’s a paradox of the rainforest; all the nutrients are locked up in the living vegetation. When a tree falls, it’s recycled almost instantly. This is why deforestation is so devastating here. Once the trees are gone, the ground turns to hard, useless clay pretty quickly.

The Savanna: It’s Not Just The Lion King

If you ask a random person to draw Africa, they’re drawing the savanna. This is the "typical" African landscape. High grass, scattered acacia trees, and a horizon that never ends. On any decent biome map of Africa, the savanna (or tropical grasslands) takes up the most real estate. It wraps around the central rainforest like a giant horseshoe.

👉 See also: Finding Your Way: What the Lake Placid Town Map Doesn’t Tell You

But "savanna" is a broad term. You have the Sahel in the north, which is a transition zone between the Sahara and the wetter grasslands. It’s harsh. It’s dusty. It’s where the fight against desertification is being lost and won every single day. Then you have the moist savannas of East Africa, the Serengeti-Mara ecosystem where the Great Migration happens.

Why aren't there more trees? Fire and elephants. Seriously. Fire keeps the woody plants from taking over, and elephants act like giant biological bulldozers. They knock down trees, which allows grass to grow, which feeds the grazers. It’s a self-sustaining cycle. If you ever visit the Kruger National Park or the Serengeti, you’re seeing a biome maintained by the very animals that live in it. It’s sort of a "landscape of fear" and "landscape of hunger" all rolled into one.

The Sahara and the Myth of the "Empty" Desert

Look at the top third of the biome map of Africa. It’s almost entirely yellow or tan. The Sahara. It’s roughly the size of the United States.

People think it’s just sand dunes. Sand (or "ergs") actually only makes up about 25% of the Sahara. The rest is hamada—barren, rocky plateaus—and salt flats. It’s an extreme biome, obviously. Some parts don’t see rain for years. But it isn't dead. There are Saharan cheetahs, addax antelopes that never need to drink water, and even crocodiles in tiny, hidden oases in the Ennedi Plateau of Chad.

The Sahara is also expanding. The "Great Green Wall" project is an ambitious attempt by African nations to plant a 15km-wide strip of trees across the entire width of the continent to stop the desert from pushing south. It’s a battle of biomes.

The Mediterranean Fringe and the Cape Floral Kingdom

At the very top and very bottom of the continent, the map changes again. You get these Mediterranean biomes. Mild, wet winters and hot, dry summers. In the north, it’s the Maghreb—Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia. It feels more like Southern Europe than sub-Saharan Africa.

✨ Don't miss: Why Presidio La Bahia Goliad Is The Most Intense History Trip In Texas

But the real superstar is at the bottom: the Fynbos.

South Africa’s Cape Floral Region is its own entire floral kingdom. That is a massive deal in the scientific community. To put it in perspective, there are six floral kingdoms in the world. Five of them cover entire continents or hemispheres. The sixth one? It’s just this tiny tip of South Africa. It has more plant diversity than the entire United Kingdom. If you look at a detailed biome map of Africa, this area is a tiny sliver, but ecologically, it’s a heavyweight. It’s fire-dependent. The plants here actually need to burn every few years to release their seeds. Nature is metal like that.

The Namib and the Kalahari: Not All Deserts Are Equal

Down south, you have another splash of desert and xeric shrubland. The Namib is widely considered the oldest desert in the world. It’s famous for those towering red dunes at Sossusvlei. It’s a coastal desert, which sounds like an oxymoron. The cold Benguela current off the coast keeps rain from forming, but it creates a thick fog. The life here—like the Welwitschia plant, which can live for over 1,000 years—literally drinks the fog to stay alive.

Then there’s the Kalahari. It’s often called a desert, but technically it’s a fossil desert or a "semi-desert." It gets too much rain to be a true desert. It’s covered in red sand, but it also has trees and enough grass to support huge herds of gemsbok and lions.

The Afro-Alpine: Islands in the Sky

This is the part of the biome map of Africa that most people ignore. Scattered across East Africa and Ethiopia are high-altitude montane grasslands and shrublands.

Think of Mount Kilimanjaro or the Simien Mountains. As you go up, you pass through different biomes like you’re traveling from the equator to the poles. At the top, you have "giant lobelias" and "giant groundsels"—plants that look like they belong on another planet. They have developed "nightly fur" (thick leaves that fold up) to protect their buds from freezing every single night. It’s "summer every day and winter every night."

🔗 Read more: London to Canterbury Train: What Most People Get Wrong About the Trip

The Ethiopian Highlands are often called the "Roof of Africa." It’s a rugged, high-altitude biome that is home to the Gelada monkey and the Ethiopian wolf, the rarest canid in the world.

Why the Lines on the Map are Lying to You

Maps are static. Nature isn't. The biome map of Africa is currently being rewritten by climate change and human activity.

- Ecological Overlap: There are no walls in nature. The transition between the savanna and the rainforest is a "mosaic" of both. These transition zones, or ecotones, are often the most biodiverse because they host species from both sides.

- The Human Factor: We’ve turned huge swaths of savanna into farmland. We’ve dammed rivers, changing wetlands into dry plains. When you look at a map from 1950 versus 2024, the biomes have physically shifted.

- The Role of Livestock: In many parts of the Sahel, overgrazing is turning semi-arid biomes into true deserts. It’s a process called desertification, and it's one of the biggest challenges facing the continent.

How to Actually Use This Information

If you’re planning to travel, work, or study the continent, don’t just look at a general map. Look at rainfall charts and elevation profiles.

- For the Adventurer: If you want to see the "Green Sahara," you head to Northern Chad during the brief rainy season. If you want the Fynbos in bloom, you hit the Western Cape in August or September.

- For the Conservationist: Understand that protecting a "biome" isn't enough. You have to protect the corridors between them. Animals like elephants and wild dogs need to move between these zones to survive.

- For the Student: Don't just memorize "Africa has five biomes." It doesn't. It has hundreds of micro-climates that intersect in ways we're still figuring out.

The real biome map of Africa is a messy, beautiful, high-stakes puzzle. It’s a story of survival, adaptation, and a lot of dust. Whether it’s the freezing peaks of the High Atlas or the steaming swamps of the Sudd in South Sudan, the continent refuses to be put into a neat little box.

Next Steps for Your Research

To get a better grip on these regions, start by looking into the "African Great Lakes" system. This isn't just water; it's a series of rift valley biomes that dictate the weather and ecology for the entire eastern side of the continent. You should also check out the Koppen-Geiger climate classification maps. They offer a much more granular look at temperature and precipitation than a standard colorful biome map will ever show you.

Dive into the specific "Ecoregions" defined by the WWF if you want to see the real complexity. It’s the difference between seeing a pixelated image and a 4K video. Once you see the nuance, you can’t go back to the basic yellow-and-green school maps.