Look at any standard Anglo Saxon England map in a textbook. You see those neat, solid colored blocks? Wessex is green. Mercia is red. Northumbria is blue. It looks like a modern game of Risk. But honestly, it’s all a bit of a lie.

The reality was messier.

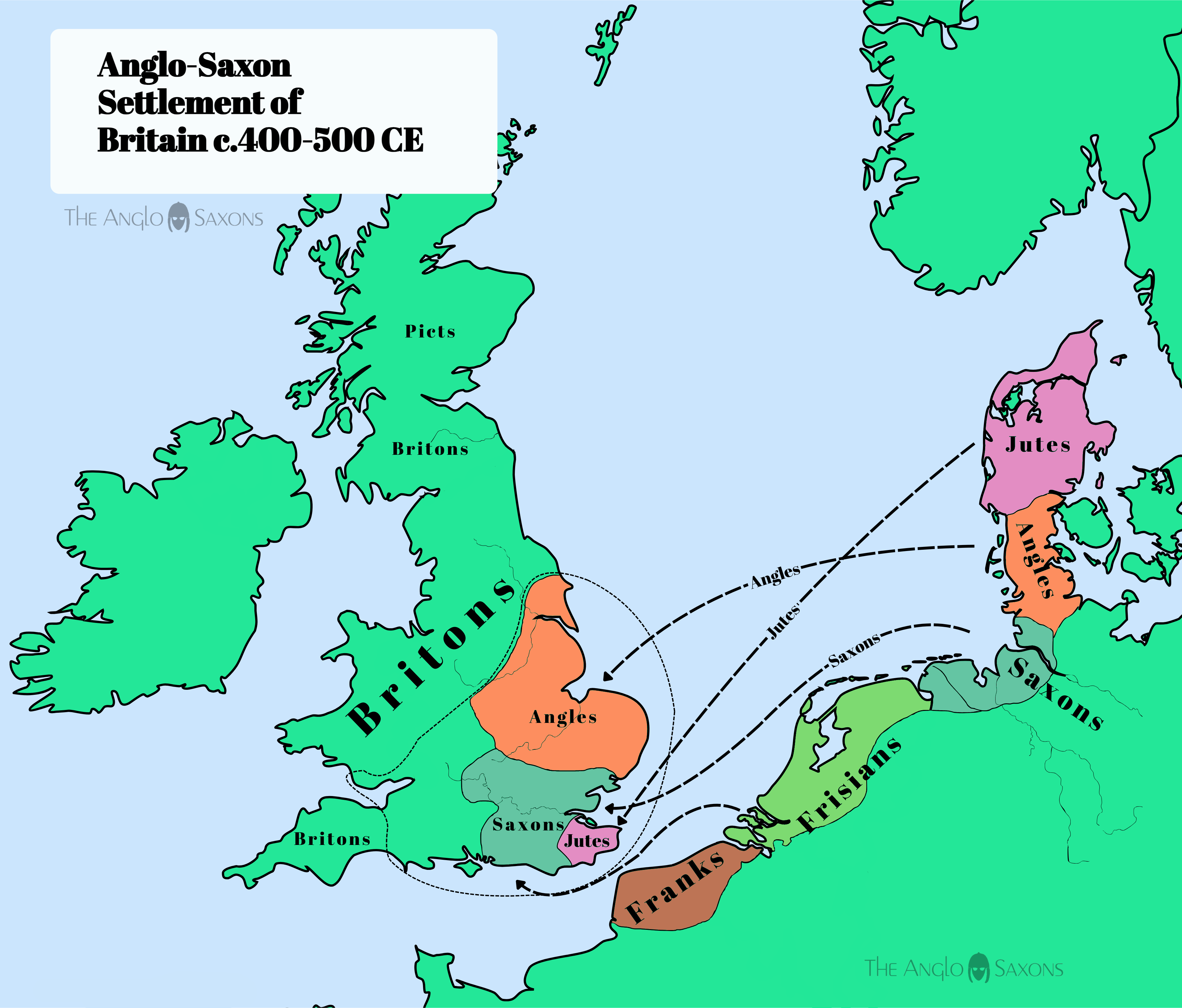

If you could teleport back to the year 750, you wouldn't find border checkpoints or clear-cut lines on the grass. You’d find a shifting, pulsing landscape of "tribal hidage," swampy marshlands that acted as natural barriers, and local warlords who changed their mind about who they worked for every time a new king swung a bigger sword. Mapping this era isn't about drawing lines; it's about tracking power.

The Heptarchy Myth and Why It Fails

We’ve all heard the term "Heptarchy." It’s that neat idea that there were seven distinct kingdoms: Northumbria, Mercia, East Anglia, Essex, Kent, Sussex, and Wessex. Historians like William of Malmesbury helped cement this idea, but it’s way too simple. It’s basically the "cliff notes" version of 600 years of history.

🔗 Read more: Traffic in Hampton Roads: Why Your Commute Still Feels Like a Part-Time Job

In the early days, the map was a swarm of smaller groups. Have you ever heard of the Haestingas? Or the Magonsæte? Probably not, unless you’re a total dark ages nerd. These were sub-kingdoms. They existed in the gaps between the "Big Seven." Over time, the big guys just ate the little guys. When you look at an Anglo Saxon England map from the 7th century versus the 9th, you’re watching a slow-motion consolidation of corporate takeovers, just with more chainmail and fewer spreadsheets.

The borders moved. Constantly.

Take the Trent Valley. One year it was the heart of Mercian power, the next it was a contested zone between the northern lords and the midland kings. If you’re trying to use a map to understand this period, you have to treat it like weather—it’s a snapshot of a storm, not a permanent fixture of the land.

Water Was the Only Real Border

In a world without paved highways (the Roman ones were crumbling by then), water dictated where people lived and where they died. If you look closely at a topographical Anglo Saxon England map, you’ll notice the kingdoms are defined by rivers and marshes.

The Fens in East Anglia were basically an inland sea. They weren't just "wet ground." They were a massive, impenetrable barrier that kept the East Angles safe from Mercian expansion for decades. You couldn't march an army through a swamp. Likewise, the Thames wasn't just a river; it was a massive political divide.

The Importance of the Danelaw Line

By the late 800s, the map changed forever. This is where the "Viking Age" kicks in. After Alfred the Great stopped the Great Heathen Army at Edington, he signed a treaty with the Viking leader Guthrum. This created the Danelaw.

This wasn't just a vibe; it was a literal line on the map. It followed the River Thames, then up the River Lea to its source, then straight to Bedford, then up the River Ouse to Watling Street. If you lived north and east of that line, you were under Norse law. You paid different taxes. You spoke a slightly different version of Germanic slang. You looked toward York or Scandinavia for leadership, not Winchester.

- The Five Boroughs: Derby, Leicester, Lincoln, Nottingham, and Stamford. These were the fortified hubs of the Danelaw.

- Wessex: The holdout. The south-west corner that eventually clawed back the rest of the country.

- The Burhs: Alfred’s "anti-Viking" network. He didn't just fight; he built. He created a system where no one in Wessex was more than 20 miles from a fortified town.

Tracking the "Bretwalda" Power Shifts

The map also tells the story of the Bretwalda—the "Britain-ruler." This wasn't an official title you inherited like a modern King; it was a status you took by force.

Early on, the power was in the south. Kent was the big player because they were closest to trade with the Franks. Then it swung north to Northumbria. Think of the massive monastic centers like Lindisfarne and Jarrow. For a century, the intellectual and political center of the Anglo Saxon England map was way up near the Scottish border.

Then came the Mercian Supremacy. Under King Offa, Mercia was the powerhouse. Offa was so confident he actually built a giant dirt wall—Offa’s Dyke—along the border with Wales. It’s still there. You can go hike it. It’s a literal scar on the map that shows exactly where one man decided his world ended and the "wild" West began.

How to Read an Anglo-Saxon Map Today

If you're looking at a map and it doesn't show the physical geography, close the tab. You need to see the forests. The Weald in the south-east was so thick it was almost uninhabited, acting as a buffer between the South Saxons and the Men of Kent.

You also need to look at place names. They are the "ghost maps" of the Anglo-Saxon world.

- Any town ending in -by or -thorpe? That’s Viking territory. Look at a map of Yorkshire vs. a map of Devon. The "by"s vanish as you go south-west.

- Towns ending in -ing? Those were the early settlements, the "people of" a specific leader.

- -chester or -caster? That’s where the Saxons moved into old Roman ruins.

Basically, the map is a graveyard of languages and lost tribes.

Putting the Map into Practice: A Real-World Itinerary

If you actually want to see this history on the ground, don't just go to London. London was often a contested, weirdly empty ruin for parts of this era. Instead, follow the power shifts.

- Sutton Hoo (East Anglia): This is where the map starts to make sense. You see the wealth of the early kings—gold from Byzantium, garnets from India. It shows that even "isolated" England was plugged into a global network.

- Tamworth (Staffordshire): The capital of Mercia. It doesn't look like much now, but this was the "Washington D.C." of the 8th century.

- Winchester (Hampshire): The heart of Alfred’s dream for a united England. The street layout today is still largely what Alfred laid out to defend against the Danes.

- Bamburgh (Northumberland): The "Capital of the North." When you stand on those cliffs, you realize why Northumbria felt like a different world compared to the soft rolling hills of Wessex.

The map of Anglo-Saxon England isn't just a historical curiosity. It explains why England looks the way it does today. It explains why a person from Liverpool sounds different than a person from London. It explains why "the North" still feels like a distinct entity.

Actionable Steps for the Amateur Historian

Stop looking at static images and start using interactive layers.

First, find a map that overlays the Roman Roads onto the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. You’ll notice the Saxons often avoided the roads for their homes but used them for their wars. It’s a fascinating disconnect.

🔗 Read more: Temperature in Germany Munich: Why Local Weather Logic Often Fails

Second, check out the Electronic Sawyer. It’s an online catalogue of Anglo-Saxon charters. If you find a charter for a piece of land near you, you can see who owned it in 900 AD. It turns a boring map into a personal connection.

Third, use the Open Domesday tool. While it’s technically from 1086 (just after the Anglo-Saxon period ended), it is the most complete record of what the Anglo-Saxon map actually looked like before the Normans paved over it. It lists every mill, every pig, and every peasant.

Don't settle for the "Seven Kingdom" myth. The real map was a chaotic, beautiful, and violent patchwork of people trying to figure out what it meant to be "English" for the very first time.

Next Steps for Your Research:

- Locate your nearest "Burh": Use the Burghal Hidage list to see if your local town was part of Alfred the Great's national defense strategy.

- Examine Toponymy: Use a local ordnance survey map to identify town suffixes (like -ham, -ton, or -by) to determine if your area was Mercian, West Saxon, or part of the Danelaw.

- Visit the Ashmolean or British Museum: View the physical artifacts, like the Alfred Jewel, to understand the craftsmanship that funded the political expansion shown on these maps.