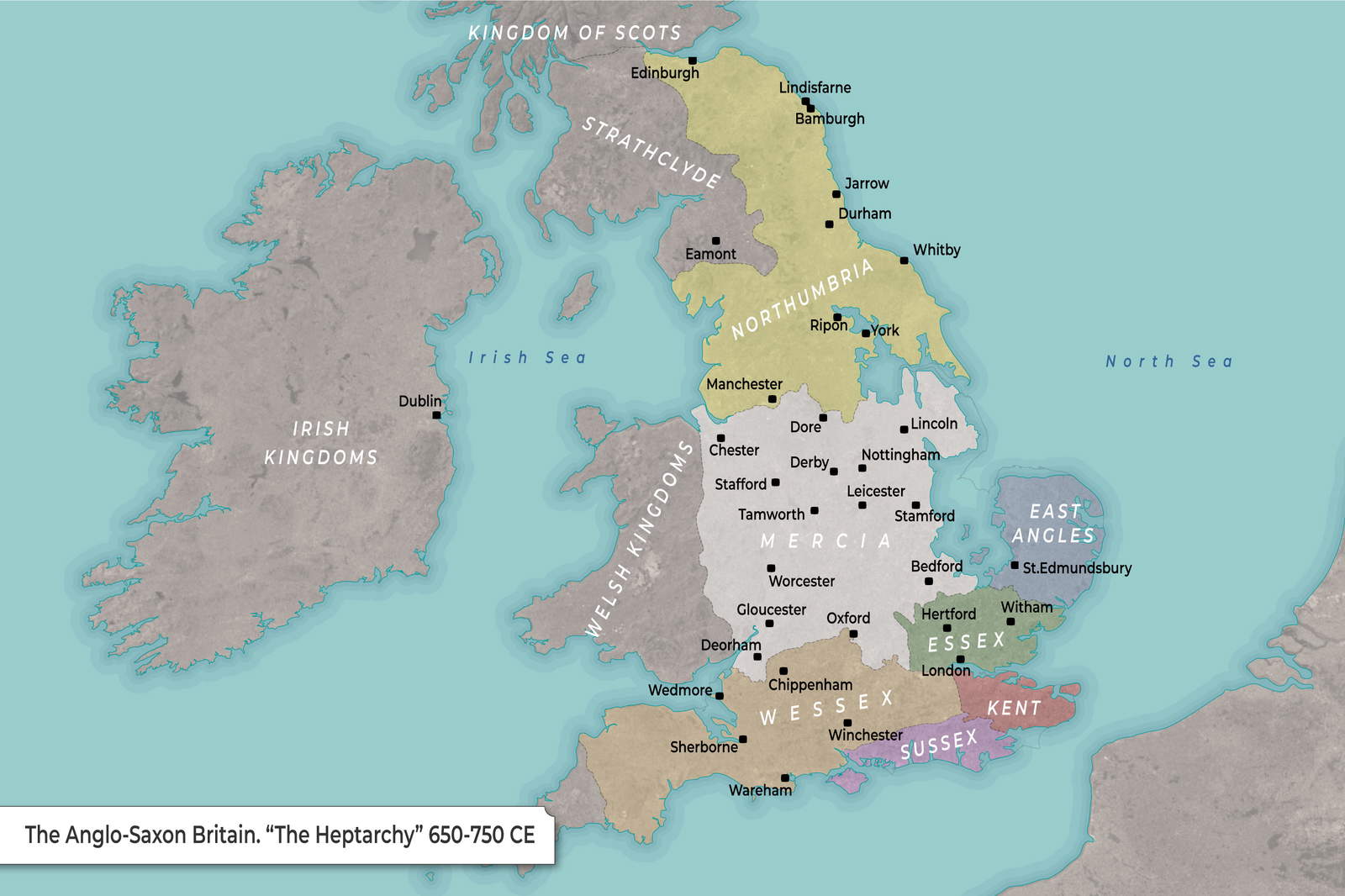

If you open a standard history textbook, you’ll likely see a very tidy anglo saxon britain map. It usually features seven neat blocks of color labeled Wessex, Mercia, Northumbria, and so on. Historians call this the Heptarchy. It looks organized. It looks like a plan.

It’s also mostly a fantasy.

The reality on the ground between 450 AD and 1066 AD was a chaotic, shifting mess of tribal boundaries that changed every time a local warlord got a lucky swing with a seax. Mapping this era isn't about drawing lines; it's about tracking a slow-motion car crash of cultures, languages, and power dynamics. You've got to stop thinking about "countries" and start thinking about "influence zones."

The Myth of the Seven Kingdoms

We love the number seven. It feels complete. But the idea that Britain was neatly divided into seven stable kingdoms—Northumbria, Mercia, East Anglia, Essex, Kent, Sussex, and Wessex—was largely popularized by later chroniclers like Henry of Huntingdon in the 12th century. He wanted to make sense of a messy past.

In reality, the anglo saxon britain map of the 6th or 7th century would have been a honeycomb of dozens of smaller territories. Have you ever heard of the Magonsæte? Probably not. What about the Haestingas? These were distinct tribal groups with their own leadership. They were eventually swallowed up by the "Big Seven," but for centuries, the map was granular.

Geography dictated the power. The fens of East Anglia acted as a massive soggy shield. The thick forests of the Weald kept Sussex isolated. If you look at a topographical map alongside a political one, you suddenly see why certain kingdoms grew and others withered. Power followed the Roman roads that still existed, but it also followed the rivers. If you controlled the Trent or the Thames, you controlled the tax man.

Blood and Soil: How the Borders Actually Moved

Imagine a border that moves ten miles every time a king dies. That was the life of a farmer in the Midlands.

Mercia is the best example of this. Under kings like Penda and later Offa, Mercia was the heavyweight champion of the 8th century. Their "map" wasn't a static border; it was a protection racket. Offa’s Dyke, that massive earthwork running along the Welsh border, is one of the few times an Anglo-Saxon ruler actually tried to draw a physical line on the dirt. It’s a 150-mile-long statement of "stay on your side."

But even then, the map was porous.

Trade didn't stop at the border of the Hwicce. People moved. Salt from Droitwich traveled across "international" lines because everyone needed to preserve meat. When we look at a anglo saxon britain map, we see hard colors, but we should be seeing gradients. The culture in northern Northumbria was heavily influenced by the Picts and Scots, while Kent was basically a cultural suburb of Frankish Gaul.

The Viking Sledgehammer

Everything changed in 865 AD.

🔗 Read more: Why the quorum of twelve apostles ages actually matter more than you think

The Great Heathen Army didn't care about the Heptarchy. Within a few decades, the traditional map was shredded. If you look at a map from 878 AD, you’ll see a diagonal line cutting Britain in half. This was the Danelaw.

To the east and north: Viking rule, Old Norse law, and different farming habits.

To the west and south: Alfred the Great’s Wessex.

This is where the anglo saxon britain map becomes most recognizable to us today. Alfred began building burhs—fortified towns. If you look at a map of modern England and see "bury" or "borough" in a town name (like Shrewsbury or Canterbury), you’re looking at a dot on Alfred’s old defense map. These weren't just forts; they were economic hubs designed to keep the Vikings out and the tax revenue in. It was a brilliant, desperate strategy that eventually allowed Alfred's grandson, Athelstan, to claim he was the King of all Britain.

Why the Geography of Religion Matters

You can't talk about these maps without talking about the Church. While kings were fighting over muddy fields, the Church was drawing its own map of dioceses.

Sometimes these overlapped. Often they didn't.

The Synod of Whitby in 664 AD is a massive turning point that maps don't show well. It decided whether Britain would follow the "Celtic" traditions of Iona or the "Roman" traditions of... well, Rome. Rome won. This meant that suddenly, the map of Britain was plugged into a European network. Monasteries like Jarrow and Lindisfarne became the Silicon Valleys of their day. They were centers of data (manuscripts) and wealth. If you want to understand why a king would march his army 200 miles north, look for the nearest wealthy abbey on the map. That's your "why."

Language as a Border

Ever wonder why people in the North of England say "beck" for a stream and people in the South say "brook"?

Your anglo saxon britain map is also a linguistic map. The "Danelaw line" I mentioned earlier is still visible in our accents today. The places ending in -by (like Derby or Grimsby) or -thorpe are Viking imprints. The places ending in -ingas (like Reading or Hastings) are pure Anglo-Saxon.

When you look at a map of these place names, you see the ghosts of the 9th century. You see where the settlers actually dug in and where they were just passing through. It's a layer of history that hasn't been erased by 1,000 years of progress.

How to Read a "Real" Anglo-Saxon Map Today

If you're looking at a map and it looks too clean, it's lying. To get a true sense of the era, you need to look for a few specific things that most "educational" maps skip.

- The Tribal Hidage: This is a 7th-century list of territories. It measures land in "hides" (the amount of land needed to support one family). A map based on the Tribal Hidage looks like a crazy quilt, not a structured empire.

- The Ridgeway and Ancient Tracks: The Anglo-Saxons used what was already there. The Icknield Way and the Fosse Way were the highways of the era. A map without these is like a map of the US without Interstates.

- Seasonal Water: Many areas that are dry land now (like the Somerset Levels) were essentially inland seas or marshes back then. Athelstan’s Britain had a lot more coastline than we do now.

Basically, the map was a living thing. It breathed. It expanded in the summer when the kings went "a-viking" or raiding, and it contracted in the winter when everyone huddled in their longhalls trying not to starve.

Actionable Steps for History Enthusiasts

If you want to go beyond just looking at a static image and actually understand the landscape of Anglo-Saxon Britain, start with these steps:

- Use the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) database: Instead of looking at political borders, search for where coins and brooches are found. A cluster of "Mercian" coins in a "Wessex" town tells you more about the real map than a line in a textbook.

- Overlay Topography: Get a physical map of the UK and layer a transparent Anglo-Saxon map over it. You will see instantly why the Kingdom of Elmet survived as a British/Celtic pocket—it was stuck in the rugged Pennines.

- Visit the "Burhs": Go to places like Wallingford or Wareham. You can still see the earthwork banks Alfred’s men built. Walking the perimeter gives you a physical sense of the scale of these "map dots."

- Look at Parish Boundaries: Surprisingly, many modern parish boundaries in England still follow the old estate lines of Anglo-Saxon thegns. They are the most enduring lines on the map.

The anglo saxon britain map isn't a finished document. Every time a metal detectorist finds a new hoard or an archaeologist digs up a previously unknown "great hall," the lines shift again. We are still drawing this map.

Don't trust the clean lines. The truth is in the mud, the rivers, and the weird names of the small towns you’ve never heard of. That’s where the real Britain lived.