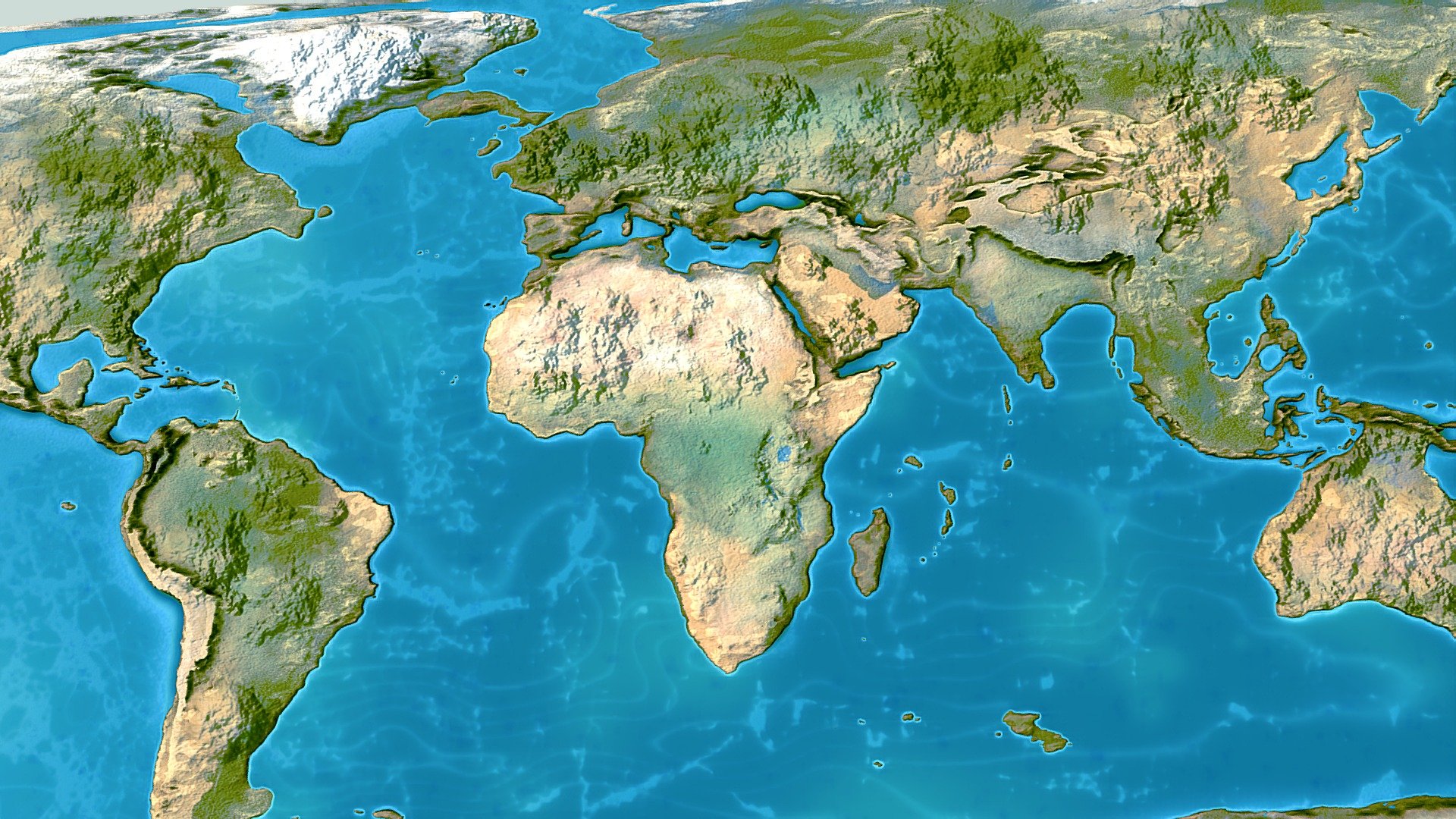

Ever get that weird feeling of vertigo when you zoom into a digital city and for a split second, you actually feel like you're falling? That’s the magic of a high-fidelity 3d map of the earth. It’s not just a gimmick for real estate anymore.

For a long time, these maps were kinda clunky. You’d see a digital version of the Eiffel Tower that looked like it was melting in the sun. Or a mountain range that felt more like a crumpled piece of grey paper than actual geography. But things changed. Fast.

We’re now living in an era where "digital twins" of our entire planet aren't just sci-fi concepts from Ready Player One. They are active, breathing data sets. If you’ve used Google Earth lately, you’ve seen the photogrammetry. It’s wild. They stitch together millions of images to recreate the world in three dimensions. But here’s the thing: most people think 3D mapping is just about making things look "cool" or "realistic." Honestly? That’s the least interesting part of it.

The tech behind the depth

How do we actually build a 3d map of the earth without just guessing what buildings look like from the side? It’s a mix of three specific technologies that finally learned to play nice together.

First, you’ve got LiDAR. Light Detection and Ranging. It’s basically hitting the ground with millions of laser pulses every second and measuring how long they take to bounce back. It’s how archeologists found those massive "lost" Mayan cities under the jungle canopy in Guatemala back in 2018. The lasers just slipped right through the trees and hit the stone ruins below.

👉 See also: The Real Story Behind the Numbers Station Cast: Why These Ghost Signals Never Went Away

Then there’s photogrammetry. This is more common. It’s what Google uses for most of its 3D cities. It takes overlapping photos from different angles—planes, drones, satellites—and uses math to calculate the distance between points. It’s why your house looks 3D, but if you zoom in too close to a tree, it looks like a green blob. Foliage is the ultimate enemy of photogrammetry.

Why satellites aren't enough

People assume satellites do all the heavy lifting. They don't. Satellites are great for flat imagery, but for a true 3D experience, you need "oblique" imagery. That’s photos taken at a 45-degree angle. Satellites are usually too high up to get that crisp, side-view detail consistently across the whole globe.

That’s where companies like Maxar and Vricon come in. They’re doing the "The Big Map" stuff. They use high-resolution satellite constellations to create what’s called a Digital Elevation Model (DEM). It captures the literal height of the terrain. If a volcano grows by three feet, they know.

More than just a pretty picture

Think about urban planning. If you want to put a new skyscraper in downtown Tokyo, you can’t just wing it. You need to know how the shadows will fall on the park next door at 3 PM in mid-October. A high-res 3d map of the earth lets planners simulate sun paths, wind tunnels, and even flood risks.

Flood modeling is probably the most "life or death" use case for this tech. Organizations like the IPCC and various national weather services use 3D terrain data to predict exactly which street corner will be underwater if a levee breaks. If your map is off by just six inches in elevation, your flood model is garbage.

Then there’s the military side of things. It's a bit grim, but the "Synthetic Training Environment" (STE) used by the US Army relies on a 1:1 scale 3D model of the globe. Pilots can fly missions in a simulator over a digital recreation of terrain they’ve never actually visited. It’s eerily accurate.

The gaming crossover

You can’t talk about 3D maps without mentioning Microsoft Flight Simulator. When that dropped in 2020, it was a watershed moment. They used Bing Maps data—about two petabytes of it—and processed it through Azure AI to generate trees, buildings, and water.

It wasn't perfect. I remember seeing a 100-story "monolith" in Australia that turned out to be a typo in OpenStreetMap data. But it proved that we can stream a 3d map of the earth in real-time to a home PC. That’s insane. We went from Flight Simulator 95 (which looked like Legos) to "I can see my actual car in my driveway" in a few decades.

The challenges: Why isn't everything 3D yet?

Money. Mostly.

Mapping the world in 3D is incredibly expensive. You need planes. You need massive server farms. You need humans to go in and fix the "melts" where the AI got confused by a glass building or a reflection on a river.

- Privacy issues: If a 3D map is too good, you can see into people's backyards or identify security features on private property.

- Data bloat: Storing a 3D model of a single city block takes up more space than a 2D map of an entire state.

- Updates: The world changes. A 3D map from 2022 is already a historical document in a fast-growing city like Dubai or Austin.

Real players in the 3D space

If you want to go beyond Google, look at Cesium. They are the open-source heavyweights. They use "3D Tiles" to stream massive geospatial datasets. If you see a high-end 3D map on a news site or a government portal, there's a good chance it's running on Cesium.

Then there's Esri. They are the "Excel" of the mapping world. Their ArcGIS Pro software is what actual scientists and city planners use. It’s not as "gamey" as Google Earth, but it’s where the real work happens.

What’s coming next?

We are moving toward "Live" 3D maps. Imagine a 3d map of the earth that isn't just a static snapshot from last year, but a live feed.

Combining IoT (Internet of Things) sensors with 3D models means we could see real-time traffic flow as moving pulses of light on a 3D grid. We could see the actual air quality levels as colored clouds hovering over specific neighborhoods. It turns the map from a reference tool into a dashboard for the planet.

💡 You might also like: Type With Russian Letters: Why Your Keyboard Is Lying To You

And don't even get me started on AR. Once glasses replace phones, the 3D map will just be... the world. You'll walk down a street and the "map" will be overlaid directly onto the buildings, showing you where the subway entrance is through a solid wall.

Practical ways to use 3D maps today

If you’re just a hobbyist or someone curious about the tech, you don’t need a billion-dollar budget to play with this.

- Google Earth Pro (Desktop): It's free. Use the "historical imagery" tool alongside the 3D view to see how a mountain or city has changed over twenty years. It's the best time machine we have.

- OpenStreetMap (OSM): Contribute to it. A lot of 3D maps rely on the "tags" users put on OSM. If you add the height of a building in your hometown, you’re helping build the global 3D model.

- EarthExplorer (USGS): If you want the raw data. You can download actual LiDAR point clouds and elevation models for free. It’s a bit of a learning curve, but seeing the "naked" earth without trees or buildings is fascinating.

- Unreal Engine / Unity: If you're a creator, you can now import real-world 3D terrain data directly into these game engines. You can literally build a game level that is a perfect replica of your own neighborhood.

The shift from flat maps to a 3d map of the earth is basically the jump from radio to television. We are finally seeing the world as it actually is—messy, vertical, and incredibly complex. It’s not just about navigation anymore. It’s about building a digital mirror of our existence that we can analyze, protect, and explore without leaving our desks.

Next time you're bored, open up a 3D view of the Grand Canyon or the Swiss Alps. Look at the shadows. Look at the way the light hits the ridges. We’ve managed to put the entire physical world into a pocket-sized screen. That’s pretty wild when you actually think about it.

To get started, download Google Earth Pro on a desktop rather than using the mobile app; the advanced measurement tools and historical layers offer far more insight into how 3D data is structured. If you're feeling more technical, head over to the CesiumJS website and check out their "Sandcastle" demos to see how 3D geospatial data is being integrated into modern web apps.