You’re staring at a dead dash, the smell of burnt insulation is lingering in the cab, and your multimeter is telling you there’s zero continuity between the battery and the starter relay. Most people assume it's a blown fuse. They check the plastic blocks in the cabin. Nothing. Then they look at the battery cable and see that weird, rubbery section of wire that looks slightly bubbled or charred. That’s your 12 gauge fusible link, and honestly, it just did its job by sacrificing its life so your entire wiring harness didn't turn into a Roman candle.

It’s a crude technology. Basically, it’s a short piece of wire, usually four gauges smaller than the circuit it protects, designed to melt before the rest of your electrical system does. In a world of high-speed circuit breakers and smart power distribution modules, the 12 gauge fusible link feels like a relic from the disco era. But even in 2026, you'll find them buried in the engine bays of trucks, classic restorations, and heavy machinery because they handle massive current spikes that would trip a standard fuse in a heartbeat.

What Actually Happens When a 12 Gauge Fusible Link Melts?

Physics doesn't care about your commute. When a dead short occurs—maybe your alternator internal regulator failed or a power wire rubbed raw against the frame—the amperage skyrockets. A standard 12 AWG wire might be rated for 20 to 40 amps depending on the insulation type and length, but a 12 gauge fusible link is designed to act as the "weakest link" in a system usually powered by an 8 gauge or 6 gauge main feed.

The insulation is the secret sauce here. Unlike standard primary wire (GPT or SXL), which might catch fire or drip molten plastic, a genuine fusible link uses Hypalon or a similar high-temp silicone-based jacket. It’s meant to contain the heat. When the conductor inside reaches its melting point, the wire disintegrates, but the jacket usually stays intact, albeit looking a bit charred or "stretchy." If you pull on a suspected bad link and it feels like a rubber band, the copper inside is gone.

Why You Can't Just Use Regular Wire

I’ve seen it a thousand times in forums and "backyard mechanic" groups. Someone says, "Just crimp a piece of 12 AWG primary wire in there, it’s the same thickness."

Don't do that.

💡 You might also like: Silicon Valley on US Map: Where the Tech Magic Actually Happens

Regular wire has PVC insulation. If a short happens again, that PVC will ignite. It will travel up the wire like a fuse on a stick of dynamite, melting every other wire it’s bundled with. You’ll go from a $10 repair to a $3,000 harness replacement—or a total loss vehicle fire. Fusible link wire is specifically engineered to be non-flammable. It’s the difference between a controlled burn and a wildfire.

Identifying the 12 Gauge Spec

In the American Wire Gauge (AWG) world, the 12 gauge fusible link is typically used to protect 8-gauge circuits. The rule of thumb has always been to go four gauges smaller than the wire you are protecting.

- Protecting an 8 AWG main line? Use a 12 gauge link.

- Protecting a 10 AWG line? Use a 14 gauge link.

- Protecting a 12 AWG line? Use a 16 gauge link.

Most OEM manufacturers, like General Motors or Ford, color-code these. For a long time, GM used a rust-orange or brown jacket for their 12-gauge links, while others might use a heavy gray. But don't trust the color alone. Check the printing on the wire jacket. It should explicitly say "Fusible Link." If it doesn't, it's just wire.

The Problem With Modern "High-Output" Upgrades

Here is where people get into real trouble. You decide to upgrade your old 60-amp alternator to a high-output 160-amp unit because you installed a winch or a massive stereo. You leave the factory 12 gauge fusible link in place.

What happens?

📖 Related: Finding the Best Wallpaper 4k for PC Without Getting Scammed

The link is now the bottleneck. It’s not necessarily "shorting," but it’s running right at its thermal limit. Over time, this heat cycles the copper, making it brittle. Eventually, you’ll get intermittent power loss. You’ll be driving down the highway, hit a bump, and the whole truck dies. Then it starts back up. That’s the internal strands of the link touching and moving as they degrade. If you upgrade your charging system, you must rethink your circuit protection. Usually, that means moving away from links and toward Mega-fuses or ANL fuses.

Installation: The "Do's" and "Hell No's"

If you're replacing a 12 gauge fusible link, your connection method is more important than the wire itself. A bad crimp creates resistance. Resistance creates heat. Heat blows the link when there isn't even a short.

- Crimp, then Solder: Use a non-insulated butt connector. Crimp it tight with a real ratcheting tool, not those $5 pliers from the grocery store. Then, flow some solder into the joint.

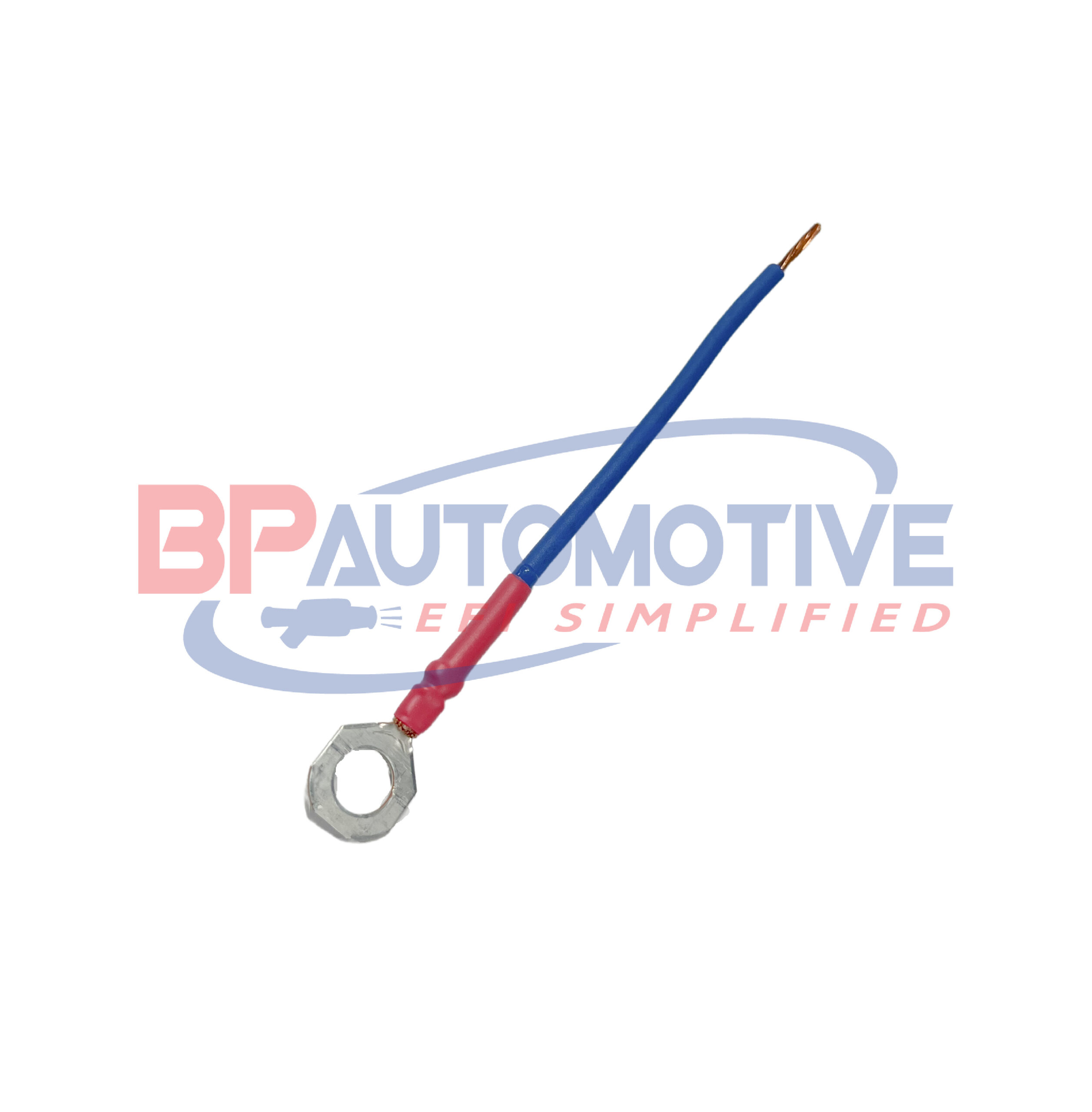

- Heat Shrink is Mandatory: Use the adhesive-lined stuff (marine grade). This seals out oxygen and moisture, preventing the copper from turning green and rotting inside the connection.

- Length Matters: A fusible link should generally be between 6 and 9 inches long. Too short, and it won't have enough "buffer" to handle its thermal properties. Too long, and you're adding unnecessary resistance to the main power feed.

- No Electrical Tape: Never just wrap the ends in black tape and call it a day. The engine bay is a violent environment of vibration and chemicals. Tape will fail in six months.

Real-World Failure: A Case Study

I remember a 1994 K1500 Silverado that kept "eating" alternators. The owner had replaced the alternator three times in a month. Each time, the parts store bench-tested the "dead" unit and said it was fine.

The culprit? A 12 gauge fusible link near the starter solenoid. It hadn't fully melted through, but it had "blown" internally just enough that it could only pass about 5 amps. When the truck was idling, everything looked okay. As soon as the headlights and A/C were turned on, the voltage would drop to 10V because the link couldn't handle the load. The owner thought the alternator was weak; in reality, the "pipe" was clogged.

Testing this requires a voltage drop test. You check the voltage at the alternator output post and then check it at the battery positive terminal. If there’s a difference of more than 0.5V, your fusible link or its connections are likely toasted.

👉 See also: Finding an OS X El Capitan Download DMG That Actually Works in 2026

Is It Time to Kill the Fusible Link?

A lot of electrical engineers argue that fusible links are obsolete. In many ways, they are. A MIDI or MEGA fuse is much more predictable. If a 100-amp MIDI fuse blows, you know exactly why. It blew at 100 amps. A 12 gauge fusible link is a bit more "analog"—it blows based on heat and time.

However, links are incredibly vibration-resistant. A fuse has a thin element that can eventually fatigue and break in a high-vibration environment (like a diesel engine or a tractor). A wire link doesn't have that problem. That's why they still persist in specific industrial and automotive niches.

Practical Steps for Repair and Prevention

If you find yourself with a melted 12 gauge fusible link, don't just replace it and drive off. A link rarely dies of old age. It dies because something went wrong.

- Scrub the Grounds: 90% of "weird" electrical issues that blow links are actually caused by bad grounds. If the electricity can't get back to the battery easily, it finds "creative" paths that spike the amperage.

- Check the Starter: On many older vehicles, the 12 gauge fusible link is hooked directly to the starter's "BAT" terminal. If the starter solenoid is dragging or the heat shield is missing, the link gets baked from the outside and the inside simultaneously.

- Buy the Right Stuff: Don't buy "fusible link wire" from a random seller on a discount site. Go to a reputable auto parts store or a dedicated wiring house like Waytek or Del City. You need to be 100% sure the insulation is the correct chemical compound.

- Keep a Spare: If your vehicle uses links, buy a 3-foot roll of 12 gauge link wire and keep it in your glovebox with some crimps. It's the difference between being stranded in the woods and making it home.

Once you’ve replaced the link, start the engine and use an infrared thermometer to check the temperature of the wire under load. It should be warm, but never hot enough to smoke or smell. If it's crossing the 180°C mark, you’ve still got a resistance issue somewhere down the line that needs hunting.

The 12 gauge fusible link is your car's final guardian. It’s the "in case of emergency break glass" solution that prevents your vehicle from becoming a bonfire. Treat it with a little respect, install it correctly, and it'll silently protect your electronics for another twenty years.

To ensure your repair lasts, check the physical routing of the wire. Make sure it isn't rubbing against any sharp metal edges or resting directly on an exhaust manifold. Even the best fusible link won't survive a mechanical "sawing" action against a vibrating frame rail. Ensure all connections are tightened to the manufacturer's torque specs, as loose nuts at the starter or alternator are the leading cause of the localized heat that triggers a link failure.