Ever watched a three-year-old try to wrangle a crayon? It’s pure chaos. They’ve got the spirit, but the fine motor control just isn't there yet. When you ask a child to trace the number 3, you aren't just teaching them a digit; you're actually asking their brain to perform a complex dance of spatial awareness and muscular precision. Most parents and even some preschool teachers jump straight into the deep end, handing over a worksheet and expecting magic.

Honestly, that’s a mistake.

The number three is notoriously tricky. Unlike the number one, which is just a straight plunge, or the number seven, which is a sharp pivot, the 3 is all about curves. Two of them. Stacked. If the top curve isn't the right size, the bottom one collapses. It’s a structural nightmare for a toddler. If we want kids to actually enjoy writing, we have to stop treating these tracing exercises like a chore and start looking at the mechanics of how a small hand moves across a page.

The Secret Geometry of the Number 3

The number 3 is basically two open circles joined at a central point. In the world of occupational therapy, this is known as a "retrace" or a "point turn." To trace the number 3 correctly, a child has to move their hand in a clockwise arc, stop their momentum completely, and then immediately reverse that momentum into a second arc.

That "stop" is where everything goes sideways.

Without that brief pause in the middle, the 3 ends up looking like a squiggly line or a very tired letter 'S'. Dr. Jean Ayres, a pioneer in sensory integration theory, often pointed out that children need to feel the movement in their bodies before they can replicate it on paper. This is why "sky writing"—using the whole arm to draw the number in the air—is so much more effective than just grinding a pencil into a piece of paper. You’ve gotta get the large muscles involved first.

Think about the physical space. A child’s hand is tiny. Their grip—usually a palmar supinate grasp at age two or three—is chunky and imprecise. Transitioning to a tripod grasp takes time. When we force them to trace the number 3 on a small scale, we're asking for micro-movements they literally haven't developed the nerves for yet.

🔗 Read more: Pink White Nail Studio Secrets and Why Your Manicure Isn't Lasting

Why Worksheets Often Fail

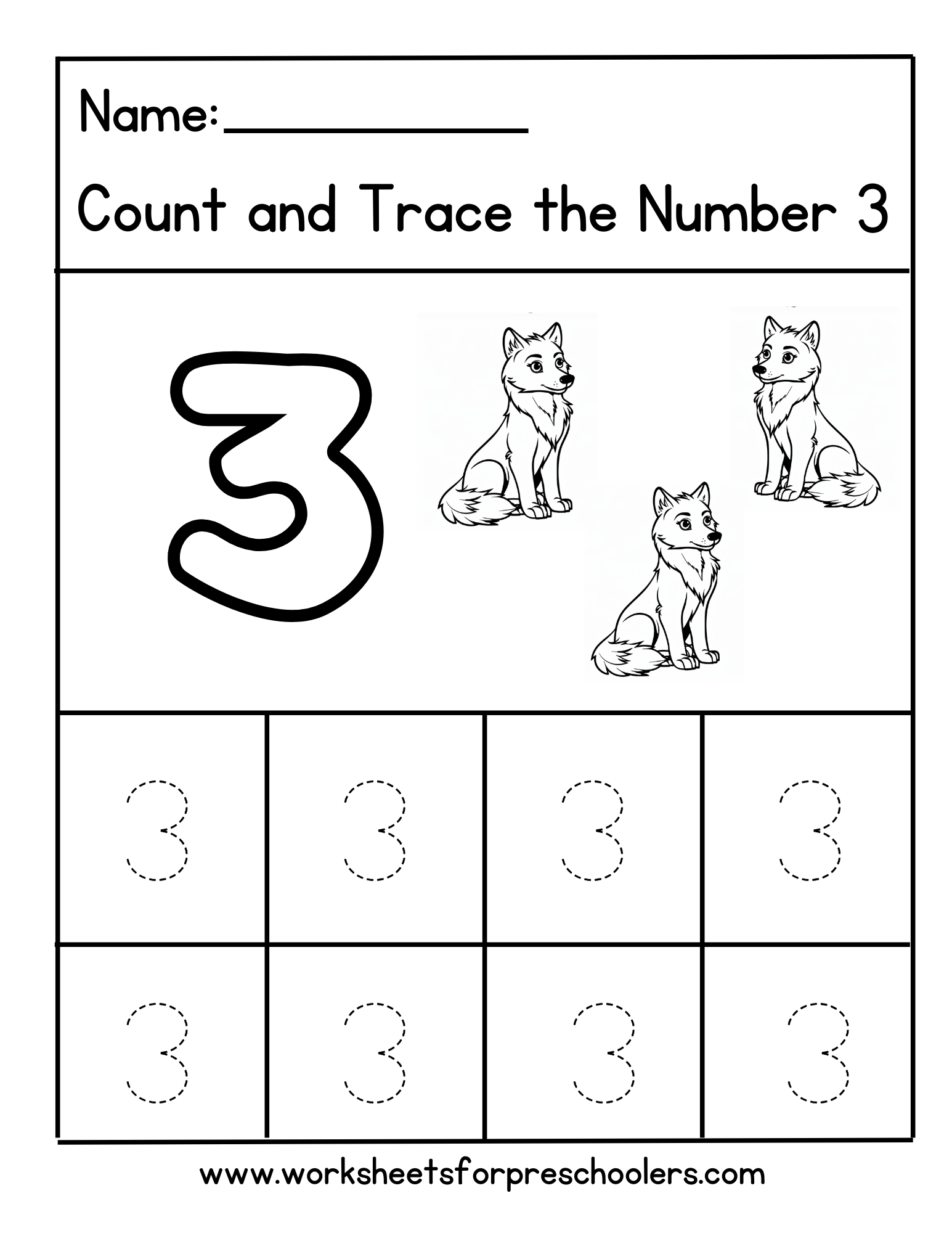

Let's talk about those dotted lines. You know the ones. They’re everywhere in "educational" workbooks you find at the grocery store.

The problem? Dotted lines can actually be a visual distraction. For a child with developing visual processing skills, a line of dots doesn't always look like a path. It looks like a bunch of individual dots. They end up "connecting the dots" one by one rather than making a fluid motion. This results in a jerky, segmented number 3 that lacks the flow necessary for fast writing later in life.

Instead of the standard dots, experts like those at Handwriting Without Tears (a program used in thousands of schools) suggest using a "continuous stroke" model. They emphasize the "Big Curve" and "Little Curve" terminology. It simplifies the language. It makes it a story.

You aren't just tracing; you're taking a little car around two big bends.

Tactile Alternatives That Actually Work

If you want to teach a kid to trace the number 3, get out of the chair. Get on the floor.

- The Sand Tray: Fill a shallow baking sheet with salt or sand. Let the kid use their index finger. There is zero resistance, and the sensory feedback of the sand against the skin helps "lock in" the shape in the brain's motor map.

- Shaving Cream: Messy? Yes. Effective? Absolutely. Smearing shaving cream on a table and drawing a 3 is peak engagement. Plus, it’s easy to erase.

- Playdough Snakes: Have them roll out a long "snake" of dough and then fold it into the shape of a 3. This builds hand strength—the literal "engine" of handwriting—while reinforcing the shape.

The Developmental Timeline (Don't Panic)

I see parents getting stressed because their four-year-old is still drawing 3s backward. Relax. It’s called "mirror writing," and it is completely normal up until about age seven. The brain is still figuring out that orientation matters. In the real world, a chair is a chair whether it's facing left or right. In the world of symbols, a 3 facing the wrong way becomes... well, nothing. Or maybe an 'E' if they're lucky.

💡 You might also like: Hairstyles for women over 50 with round faces: What your stylist isn't telling you

Most children won't have the "refined" motor skills to trace the number 3 with true accuracy until they are between 4 and 5 years old. Before that, it’s all about the "pre-writing" strokes. Can they draw a circle? Can they draw a cross? If they can't draw a cross (+), they aren't ready for the 3. The cross requires crossing the midline of the body, a neurological milestone that is a prerequisite for complex letters and numbers.

Teaching the "Middle Stop"

The most important part of the 3 is the "bump" in the middle. I like to tell kids that the 3 is like a bee flying into a flower, getting some honey, and then flying into another flower.

"Around the tree, around the tree, that’s the way we make a three."

It’s a classic rhyme for a reason. It gives the rhythm. Rhythm is the secret sauce of handwriting. When you trace the number 3, you should be saying the steps out loud. This engages the auditory learning center alongside the visual and kinesthetic ones.

Moving Toward Independence

Once the child has mastered the "messy" versions—the sand, the shaving cream, the giant sidewalk chalk versions—then you move to the paper. But don't start with college-ruled lines. Start with "Box Writing."

Give them a large square. Tell them the 3 has to touch the top, the side, and the bottom. This provides "boundaries." Boundaries are comforting for a kid who feels like their hand is a wild animal they can't quite control.

📖 Related: How to Sign Someone Up for Scientology: What Actually Happens and What You Need to Know

Avoid the urge to correct every single mistake. If they trace the number 3 and it looks like a lumpy potato, but they started at the top and moved in the right direction? That’s a win. Celebrate the process, not the product. The precision will come as the bones in their wrists—which don't even fully ossify until later in childhood—actually harden and provide a stable base for movement.

Real-World Practice

Forget the desk. Take it outside.

Use a spray bottle filled with water on the driveway. Have them "disappear" a 3 you’ve drawn in chalk by tracing over it with the water stream. This builds the "point and aim" muscles.

Or, use a flashlight in a dark room. You "draw" the 3 on the wall with your light, and they have to follow it with theirs. It’s basically trace the number 3 but in 3D space. It’s fun, it’s low-pressure, and it works.

Actionable Steps for Success

Ready to help a little one master the curves? Skip the boring stuff and try this sequence:

- Start Big: Use sidewalk chalk or a finger in a tray of flour. The bigger the movement, the easier it is for the brain to remember.

- Focus on the "Backtrack": Remind them that the middle of the 3 is where the pen stops and goes back out on the same path for a tiny bit. This prevents the "snowman" look where the two circles don't actually touch.

- Use Visual Cues: Put a green dot at the top (Go) and a red dot at the middle "stop" point. It gives them a target.

- Limit Repetition: Don't make them write fifty 3s. Make them write three really good ones. Quality over quantity prevents the hand fatigue that leads to bad habits.

- Check the Grip: If they’re white-knuckling the pencil, they’re going to struggle with the curves. Give them a smaller pencil—golf pencils are actually better for kids because they force a more mature grip.

By the time they get to kindergarten, the act of writing shouldn't be a struggle. It should be a tool. When a child can effortlessly trace the number 3, they stop thinking about the "how" and start thinking about the "what." They aren't just drawing lines; they're communicating. That’s the real goal. Stop focusing on the perfection of the line and start focusing on the confidence of the hand. Once they feel like they can do it, they usually will.