You don't just "listen" to an album like this. Honestly, the first time I sat through the whole thing, I felt like I needed to apologize to someone, though I wasn't sure who. Xiu Xiu A Promise isn't background music for a dinner party or something you throw on while cleaning the kitchen. Released back in February 2003 on the 5 Rue Christine label, it’s a record that actively tries to push you away while simultaneously begging you to stay.

Jamie Stewart, the mastermind behind the project, has always been an outlier. But in 2003? This was a whole different level of raw.

The album is basically a collection of open wounds. It’s messy. It’s uncomfortable. It’s arguably the most important work in their massive discography because it defined the "Xiu Xiu sound" before that sound became a known commodity in the experimental scene.

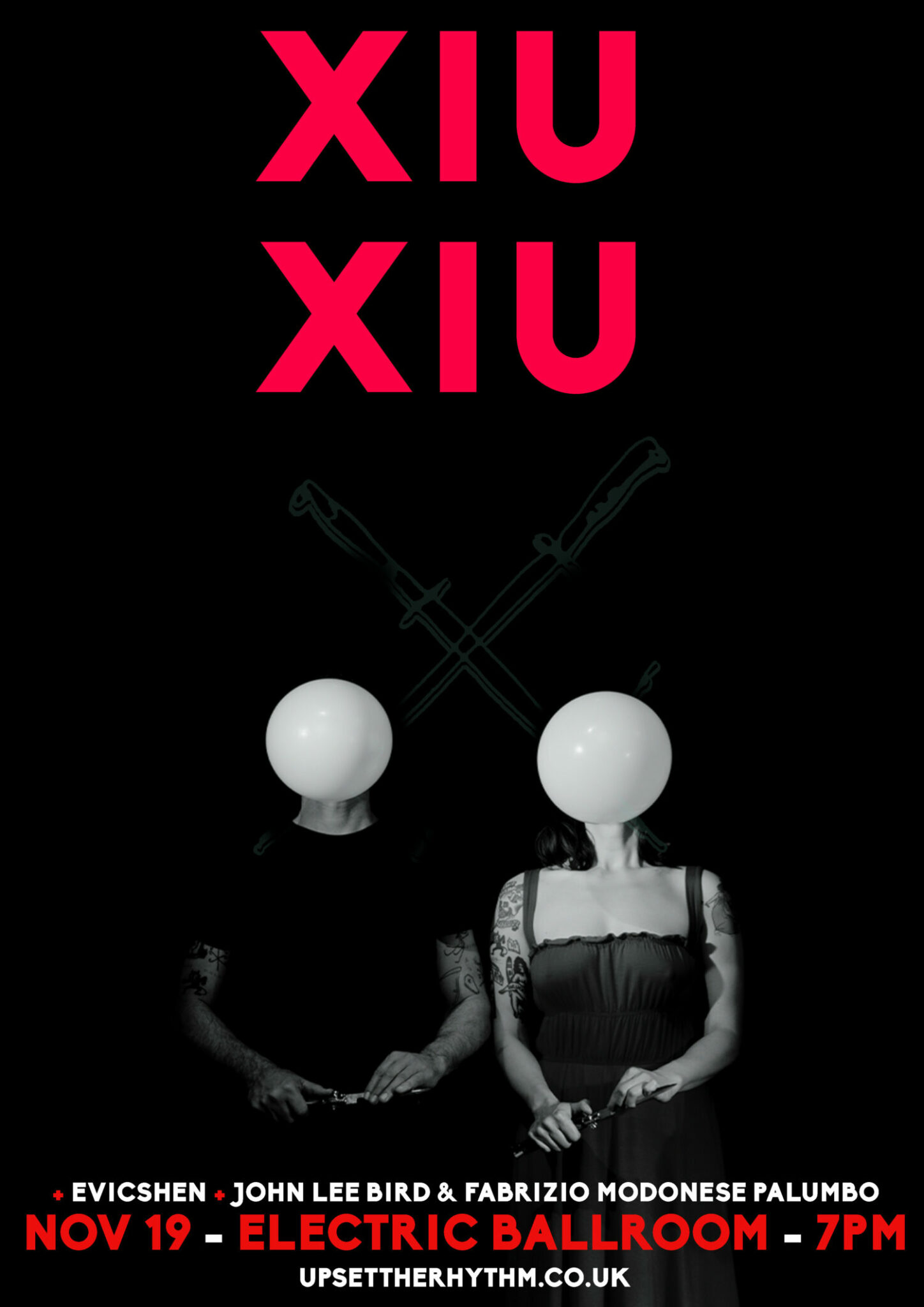

The Story Behind That Cover Art

Let’s address the elephant in the room. Or rather, the naked man on the bed.

The cover of Xiu Xiu A Promise is legendary for all the wrong (and right) reasons. It’s a photo Jamie took in a hotel room in Hanoi, Vietnam. He met a young homeless man at a gay cruising spot and, instead of the sex the man was offering for money, Jamie paid him to pose for a photo with a rubber baby doll.

It’s an image of deep, localized exploitation and weirdly clinical sadness.

👉 See also: Christopher McDonald in Lemonade Mouth: Why This Villain Still Works

For years, many record stores wouldn't even stock it without a big orange sticker covering the guy's lap. Jamie once mentioned that the sticker was a nod to Todd Solondz’s film Storytelling, but the point wasn't the nudity—it was the transactional hollowness of the moment. That feeling of "transactional hollowness" is the DNA of the entire record.

Why "Fast Car" Is Actually Terrifying

Everyone knows the Tracy Chapman original. It’s a classic, hopeful-yet-tragic folk-pop anthem. But Xiu Xiu's version on this album is a total deconstruction.

Jamie Stewart doesn't sing it so much as he weeps it over a skeletal, shivering arrangement. He famously said he chose this song because it has no resolution. The characters don't get away. They don't find a better life. They just get older and more tired.

- The Vocals: Stewart’s voice does this "quivering" thing that people either love or find physically repulsive.

- The Mood: It feels like watching a car crash in slow motion where nobody comes to help.

- The Intent: It recontextualizes a radio staple into a piece of pure, avant-garde horror.

A Promise Track-by-Track: What Really Happened

If you look at tracks like "Blacks," you’re hearing literal quotes. Jamie has said that many of the lines in that song were things his father said before committing suicide. That’s not "artistic license." That’s a transcript of trauma.

"Sad Pony Guerrilla Girl" starts the album with a deceptive acoustic strum, but by the time you get to "Walnut House," the production is crumbling. "Walnut House" is about the nursing home where Stewart’s grandmother was dying. It’s a song about dementia and the physical rot of the human body.

✨ Don't miss: Christian Bale as Bruce Wayne: Why His Performance Still Holds Up in 2026

Then there’s "20,000 Deaths for Eidelyn Gonzales, 20,000 Deaths for Jamie Peterson." It’s noisy. It’s chaotic. It reflects a period in Jamie’s life that he has since described as being "out of his mind." He was dealing with his father's death and a string of personal failures that would have broken most people. Instead, he made this.

The Technical Weirdness

People call this "noise pop," but that’s a bit of a cop-out.

The record uses gamelan influences, weird electronic spikes, and "gay dance music" rhythms that are intentionally mismatched with the lyrics. One second you're hearing a Casio keyboard that sounds like a toy, and the next, a wall of industrial static hits you in the face.

It was recorded partly at home, which gives the vocals an uncomfortably intimate quality. It’s like Jamie is whispering directly into your ear, but he’s also crying, and you can’t back away from the speaker.

Key Personnel on the Record:

- Jamie Stewart: Vocals, pretty much everything else.

- Cory McCulloch: Producer and early collaborator who helped shape the "broken" sound.

- Yvonne Chen & Lauren Andrews: Provided the additional instrumentation that keeps the album from being just one guy's breakdown.

The "Ian Curtis Wishlist" Logic

The album ends with "Ian Curtis Wishlist."

🔗 Read more: Chris Robinson and The Bold and the Beautiful: What Really Happened to Jack Hamilton

Jamie explained that an "Ian Curtis wish list" is a list of things you’ve convinced yourself you want to happen, even though you know they never will. It’s a beautiful, doomed sentiment. It ties the whole record together—this idea of promising things to yourself or others that you have no intention or capability of keeping.

The song doesn't provide a happy ending. It just stops.

How to Approach the Album Today

If you're coming to Xiu Xiu A Promise in 2026, you're looking at a piece of history. This album paved the way for the "sad boy" trope in indie music, but it’s way more visceral than anything you’ll find on a "Deep Focus" Spotify playlist.

- Don't skip tracks. The album is a narrative arc of a mental state.

- Read the lyrics. Especially on "Brooklyn Dodgers" and "Pink City." The specificity is where the power lies.

- Listen on headphones. You need to hear the tiny, clicking glitches and the way the panning moves.

This isn't an album about being "sad." It's an album about being shattered. It’s a document of a person trying to survive the worst year of their life by turning that pain into something you can hold in your hands. It’s ugly, it’s beautiful, and it’s one of the few records that actually earns the title of a "masterpiece."

Your next move: Find the 2017 expanded reissue on vinyl. It includes liner notes by Jamie Stewart that explain the context of each track in detail, plus bonus tracks like "Sad Girl" that give even more insight into the Knife Play era transition. Sit in a dark room, put on the "Ian Curtis Wishlist," and just let it happen.