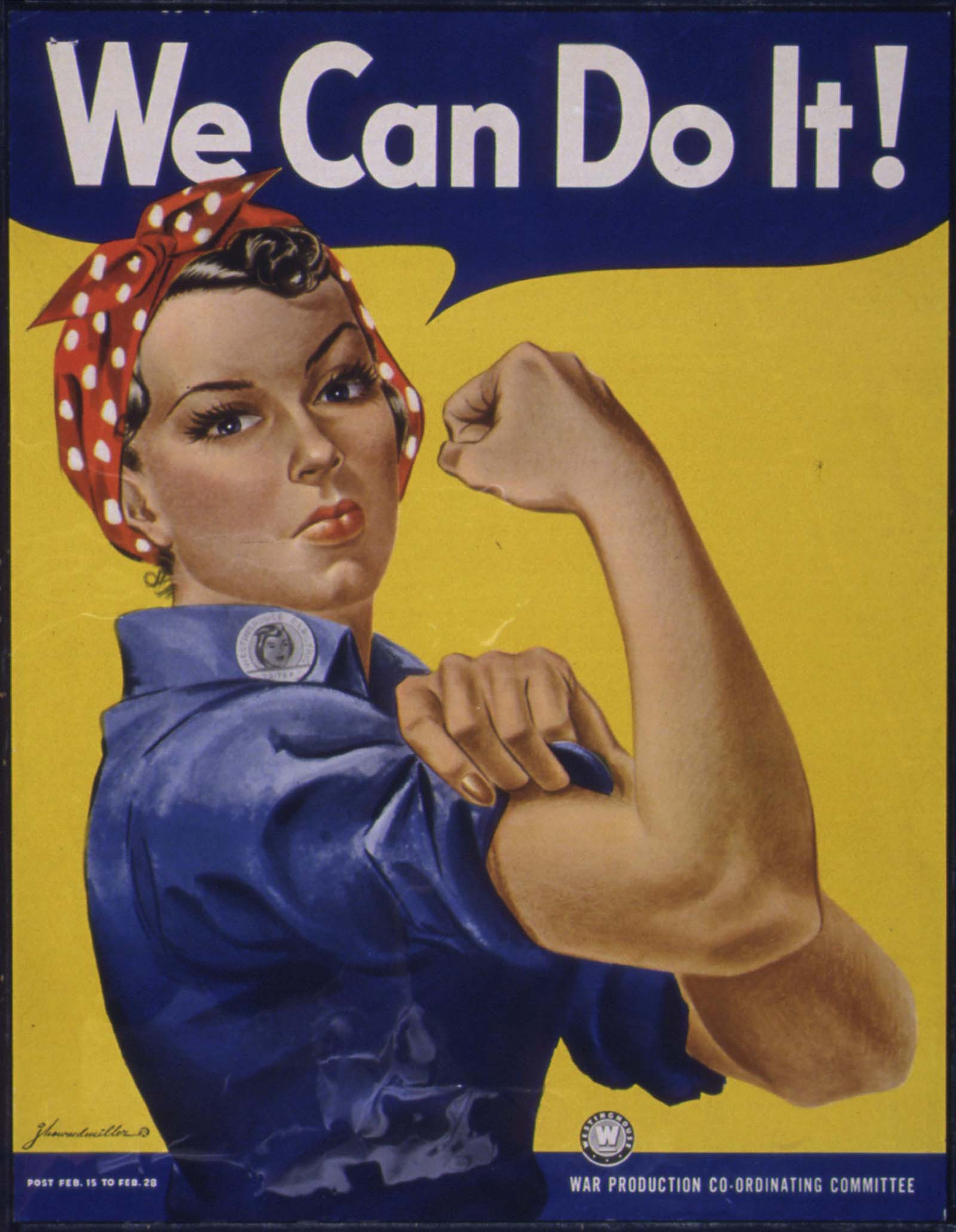

You’ve seen the poster. The yellow background, the blue denim shirt, the flexed bicep, and that "We Can Do It!" slogan that’s been slapped on everything from coffee mugs to dorm room walls. But here is the thing: Rosie the Riveter wasn't really a single person, and the reality of WWII women in the workforce was a lot messier, louder, and more complicated than a polished propaganda poster suggests.

It changed everything.

Before the attack on Pearl Harbor, the "ideal" American woman was essentially a domestic manager. If she worked, she was probably a teacher, a nurse, or a secretary. Then, suddenly, the government was begging these same women to pick up a blowtorch. By 1945, nearly one out of every three workers in U.S. industries was a woman. We aren't just talking about filing papers; we are talking about women building B-29 bombers, handling toxic chemicals in munitions plants, and driving heavy trucks.

It was a massive, nationwide improvisation.

The Massive Shift to Heavy Industry

When the U.S. entered the war, the labor shortage was catastrophic. Millions of men were shipped overseas, leaving gaping holes in the production lines that were supposed to supply them. The solution? Women. Between 1940 and 1945, the female labor force grew by 50%.

Interestingly, the biggest jump wasn't necessarily young, single women who were already looking for adventure. The real shift happened with married women. For the first time in American history, there were more married women working than single ones.

Why? Because they had to.

Take the aircraft industry, for example. In 1940, it was almost entirely male. By 1943, women made up about 65% of the total workforce in that sector. They were riveting fuselages and installing complex wiring in the "Flying Fortresses." It wasn't just a job; it was a grueling, eight-to-ten-hour shift in loud, dangerous factories. They wore coveralls instead of dresses and tied their hair back in bandanas—not for fashion, but because getting your hair caught in a lathe could be fatal.

📖 Related: Is there actually a legal age to stay home alone? What parents need to know

It Wasn't Just "Rosie"

The media loves the Rosie archetype, but the actual demographics of WWII women in the workforce were incredibly diverse.

Black women, in particular, faced a double-edged sword. While the war opened up industrial jobs that were previously closed to them, they were often the last hired and the first assigned to the most dangerous, "dirty" work in the plants. Figures like Mary Townsend, who worked at the Los Angeles Dodge plant, represent thousands who fought for the right to work in high-paying defense roles through the Fair Employment Practices Committee. They weren't just fighting the Axis powers; they were fighting Jim Crow on the factory floor.

Then you have the WASPs—Women Airforce Service Pilots. These women flew military aircraft from factories to bases, tested repaired planes, and even towed targets for live-fire practice. They weren't "officially" military at the time, which is a bit of a historical travesty, but they logged over 60 million miles in the air.

The Pay Gap and the "Double Shift"

Let's be real: the "equal pay for equal work" idea wasn't exactly a priority in 1942. Even though the National War Labor Board suggested in 1942 that women should be paid the same as men for the same jobs, it rarely happened.

Employers often reclassified jobs.

If a man’s job was "Heavy Lifting," they’d break it into two parts, call it "Light Assembly," and pay the women less. On average, women in wartime industries earned about 53% of what the men they replaced had been earning.

And then there was the "double shift."

👉 See also: The Long Haired Russian Cat Explained: Why the Siberian is Basically a Living Legend

A woman would work ten hours at the shipyard, then come home to a world where grocery stores were depleted by rationing and childcare was almost non-existent. There were no microwave dinners. There were no robot vacuums. You had to stand in line for meat, manage copper stamps for gas, and somehow keep a household running. The stress was immense.

The government eventually realized that if they wanted women to stay on the line, they had to help. This led to the Lanham Act, which funded the first federally subsidized childcare centers in the U.S. It was a radical experiment in social policy, born entirely out of the desperation for more bombers and tanks.

Why Everyone Thought it Was Temporary

The propaganda of the time was very specific. It told women that their work was "for the duration." The idea was: Go help the boys, save the world, and then get back to your kitchen as soon as the ink is dry on the peace treaty.

Kinda wild, right?

The Bureau of Labor Statistics shows that by 1944, a huge majority of these women—about 75% to 80%—actually wanted to keep their jobs after the war. They liked the financial independence. They liked the feeling of being skilled. But when the men came home in 1945 and 1946, the "pink slips" started flying.

In the automobile industry, the percentage of women plummeted almost overnight. Many women were forcibly laid off to make room for returning veterans. This wasn't a suggestion; it was often a requirement.

Society tried to put the toothpaste back in the tube. The 1950s image of the suburban housewife was, in many ways, a reaction to the "threat" of the independent wartime woman. But the tube was already crushed. Even if they were pushed out of the factories, women didn't just disappear from the economy. They shifted into service sectors, and the labor participation rate for women never actually dropped back to those pre-1940 levels.

✨ Don't miss: Why Every Mom and Daughter Photo You Take Actually Matters

The Legacy We Still Live With

The era of WWII women in the workforce didn't just win the war; it rewired the American brain. It proved that the "weaker sex" could handle heavy machinery and complex logistics just as well as anyone else.

It laid the groundwork for the 1960s feminist movement. The daughters of the Rosies watched their mothers build planes and then watched them get told to go back to being "just" housewives. That disconnect fueled a lot of the social change that came later.

Honestly, the most important takeaway is that it proved how quickly society can change when it has to. Barriers that seemed permanent for decades vanished in months when the stakes were high enough.

Actionable Insights for Today

Understanding this history isn't just about trivia; it’s about recognizing patterns in labor and gender.

- Analyze the "Crisis Pivot": Much like the shift during the 2020 pandemic, WWII shows that labor markets are more flexible than we think. If you are in a career rut, look at sectors that are currently "desperate"—that’s where the barriers to entry usually drop.

- Look for the "Shadow Labor": The wartime childcare crisis reminds us that work isn't just about the office; it’s about the support systems at home. If you're a manager, understand that "work-life balance" isn't a modern luxury—it was the single biggest reason for turnover in 1943.

- Document Your Skillset: One of the tragedies of the post-war era was that women’s technical skills were dismissed as "temporary." In your own career, ensure your diverse skills are documented and portable, so no one can tell you your expertise was just "for the duration."

- Support Pay Transparency: The pay gap of the 1940s existed because of job "reclassification." Modern pay transparency laws are the direct descendants of the struggles women faced in those shipyards.

The story of women in WWII is often told as a neat, patriotic little vignette. But it was actually a gritty, exhausting, and revolutionary period that fundamentally broke the old mold of what a woman’s life "should" look like. We are still living in the world they built—rivet by rivet.

To dig deeper into specific archives, you can explore the National Archives' records on Women in the Workforce or the Library of Congress's Veterans History Project, which contains first-hand accounts from women who served in both industrial and military capacities. Understanding the specific stories of the 350,000 women who served in uniform alongside those in the factories provides a more complete picture of the total mobilization required.

Examine the primary sources, look at the actual payroll records from companies like Boeing or Kaiser Shipyards, and you'll see that the history is far more impressive than a simple yellow poster.