Nature is weird. We think of it as this big, peaceful escape from our phones and our bosses, but William Wordsworth saw it as a mirror. A really uncomfortable mirror. Back in 1798, he sat by a grove and wrote Lines Written in Early Spring, and honestly, it’s less about the birds and more about how humans are kind of failing at being alive.

He’s sitting there. He’s happy. Then, boom—he’s depressed.

It’s that specific brand of "nature-induced existential crisis" that hits you when you realize a tree is doing a better job of existing than you are. Wordsworth wasn't just some guy looking at flowers; he was a radical. He was reacting to the Industrial Revolution, sure, but also to the internal chaos of being a person. This poem is a cornerstone of the Lyrical Ballads, the book he wrote with Samuel Taylor Coleridge that basically broke the rules of poetry by using "real" language.

The Raw Reality of Lines Written in Early Spring

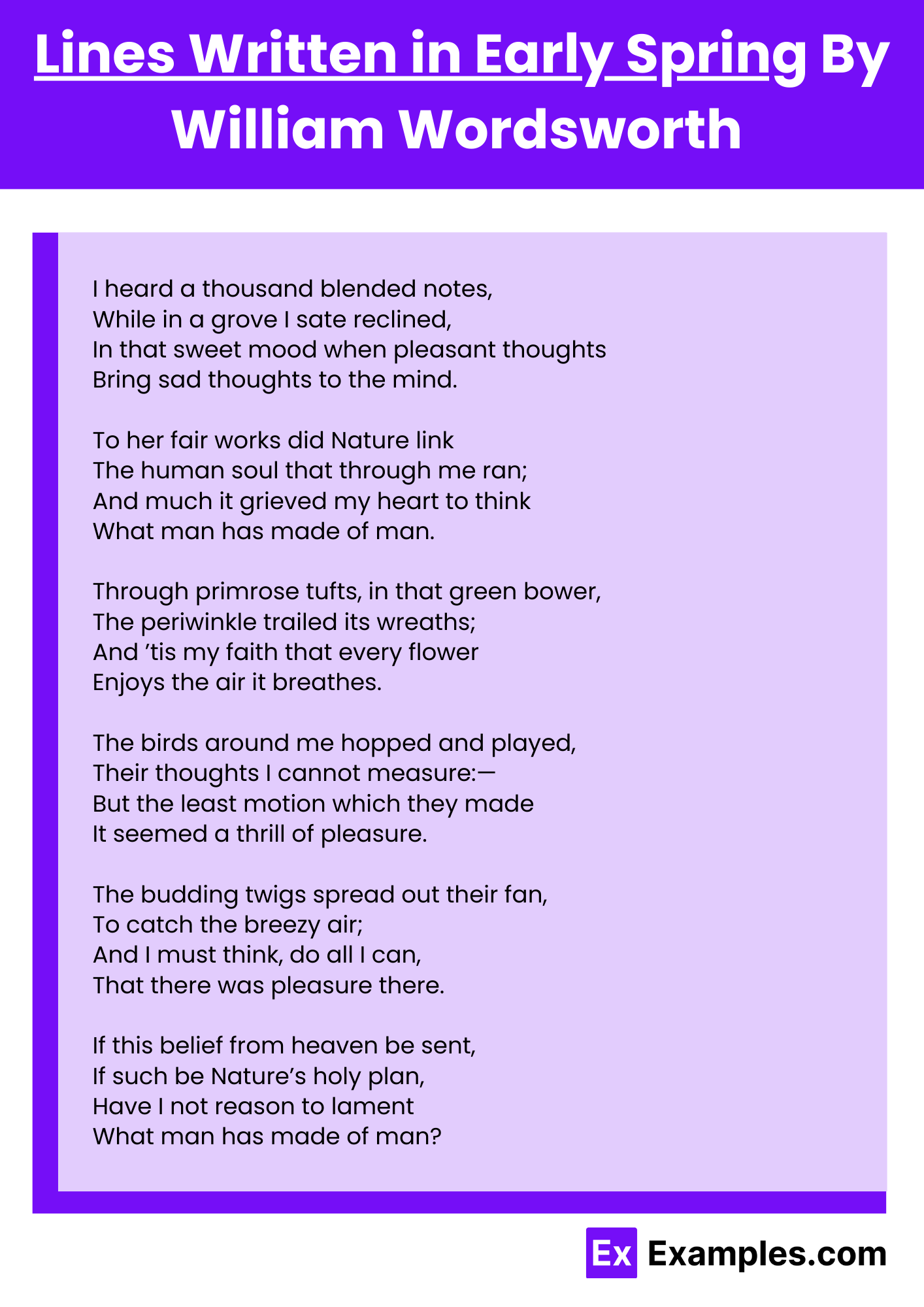

You’ve probably heard the most famous bit: "Have I not reason to lament / What man has made of man?" It’s a gut punch. Most people think of Romantic poetry as flowery and soft. This isn't that. It’s an indictment.

Wordsworth is lounging in a grove. He hears a thousand blended notes. Everything seems connected. He looks at the periwinkle and the primrose and he genuinely believes—or wants to believe—that these plants are actually enjoying the air they breathe. It sounds a bit "woo-woo" by 2026 standards, but to him, it was a literal belief in panpsychism, the idea that everything has a soul or a consciousness.

The structure is simple. It’s a ballad meter. But the thoughts are heavy. He’s contrasting the "holy plan" of nature with the absolute mess humans have made of their social structures.

Why the periwinkle matters

Let's look at the actual imagery. He mentions the periwinkle trailing through wreaths of primrose tufts. He’s not just listing plants because they look pretty in a garden. He’s observing a community. In his mind, these plants aren’t competing; they are coexisting in a way that humans, with our wars and our class systems, simply aren't.

📖 Related: Beamer’s 25: What Really Happened to Roanoke’s Favorite Hokie Hangout

He uses the word "pleasure" repeatedly. The birds hop and play. He admits he can’t measure their thoughts, but he insists their every motion feels like a "thrill of pleasure."

It’s an observation of effortless being.

The "What Man Has Made of Man" Problem

When Wordsworth wrote Lines Written in Early Spring, the world was changing fast. The French Revolution had turned incredibly bloody, disillusioning many young radicals. He was watching the start of a world where people were being pulled into factories, separated from the soil, and pitted against each other for survival.

He’s asking a hard question: If nature is built on a "holy plan" of joy, why are we so miserable?

Is it because we’ve separated ourselves? Probably.

A Radical Shift in Language

Before this poem and the rest of the Lyrical Ballads, poetry was stuffy. It was written in "poetic diction." You had to use big, fancy words and talk about gods and heroes. Wordsworth said no. He wanted to write in the "language of men."

That’s why this poem feels so accessible. It’s not hiding behind complex metaphors. It’s a guy sitting in the woods, feeling bad about the world. It’s relatable.

- The Meter: It’s mostly iambic tetrameter mixed with trimeter. It has a song-like quality.

- The Tone: Conversational but deeply melancholic.

- The Setting: A small grove, likely near Alfoxden House in Somerset, where he was living at the time.

Honestly, the simplicity is what makes it stick. You don't need a PhD to understand that he's sad because humans are mean to each other while the flowers are just vibing.

Misconceptions About the "Nature" Part

A lot of people think Wordsworth was just a "nature poet." That’s a bit of a reduction. He was a "human nature" poet. The trees are just the backdrop.

In Lines Written in Early Spring, the environment is a baseline for what health looks like. It’s a diagnostic tool. If the budding twigs are "spreading out their fan to catch the breezy air," and we are sitting inside worrying about our social standing, we are the ones who are broken, not the world.

📖 Related: Ladybug Coloring Pages: Why They Actually Matter for Early Childhood Development

He’s not saying nature is a playground. He’s saying nature is the standard.

Does nature actually feel pleasure?

Scientists today might argue with Wordsworth on this one. We know plants respond to stimuli, but "pleasure" is a human construct we project onto them. But that’s missing the point of the poem. Wordsworth isn't writing a biology textbook. He’s writing about the necessity of joy.

He argues that if this belief (that everything in nature is happy) is sent from heaven, then our failure to be happy is a spiritual failure.

It’s a heavy burden to put on a spring afternoon.

How to Apply Wordsworth’s Perspective Today

We are more disconnected now than he ever was. He was worried about steam engines; we’re worried about algorithms. The "man has made of man" line feels even more relevant when you look at how we treat each other online or how we’ve managed the environment since 1798.

If you want to actually "use" this poem, don't just read it. Do what he did.

Go find a spot. Sit. Stop looking at your watch.

Practical steps for a "Wordsworthian" Reset

- Find a "Grove": It doesn't have to be a forest. A park bench or a backyard works. The key is to be still enough that the birds stop noticing you’re there.

- Observe the "Thrill of Pleasure": Look for movement that isn't productive. A bird hopping, a leaf twitching in the wind. Stop trying to find a "reason" for it.

- The Contrast Check: Ask yourself honestly: what parts of your current stress are "man-made"? Is it a deadline? A social expectation? Compare that to the "holy plan" of the grass growing.

- Acknowledge the Lament: It’s okay to be sad about the state of the world. Wordsworth was. The poem doesn't end with a happy solution; it ends with a question.

The Nuance of the Ending

The poem ends on a note of lament. He doesn't find a way to fix humanity by the last stanza. He just sits with the grief. This is important because it validates the feeling of being "out of sync."

Sometimes, the most "human" thing you can do is recognize that you’ve lost the plot.

Summary of the "Holy Plan"

Wordsworth suggests that joy is the default state of the universe. We are the outliers. By observing Lines Written in Early Spring, we aren't just looking at pretty pictures; we are looking at a roadmap back to a version of ourselves that isn't so fractured.

It’s about re-linking the human soul to the "fair works" of nature.

It’s hard. It’s uncomfortable. But according to William, it’s the only way to stop the lament.

📖 Related: 13 jordans black and gold: What Most People Get Wrong

Actionable Takeaways

- Read the full text of Lyrical Ballads to see how this poem fits into the larger movement against industrialization.

- Practice active silence for 15 minutes in a natural setting to test Wordsworth’s theory of "perceived pleasure" in non-human life.

- Audit your "man-made" stressors this week. Identify which ones are strictly social or digital and try to distance them from your core sense of well-being.

- Write your own "Lines": Try to describe a single natural observation without using technical or "smart" words. Stick to the "language of men."

The goal isn't to become a hermit in the woods. It’s to carry that "grove" mindset into the chaos of modern life. Wordsworth didn't stay in that grove forever; he went back to the world, but he went back with a better understanding of what he was missing.