You probably sang it in a basement Sunday school. Or maybe you heard it belted out at a protest on the news. It’s one of those tunes that feels like it’s been around since the dawn of time, even though it hasn't. But honestly, the words to this little light of mine song are way deeper than just a catchy childhood melody about a flickering candle.

Most people assume it’s a traditional spiritual born in the fields of the 19th-century American South. It isn't. Not exactly. Harry Dixon Loes, a teacher and composer, is often credited with writing it in the 1920s, though its DNA is definitely intertwined with the African American oral tradition. It’s a hybrid. A mix of formal composition and the raw, unyielding spirit of folk music.

The Verses You Forgot (or Never Knew)

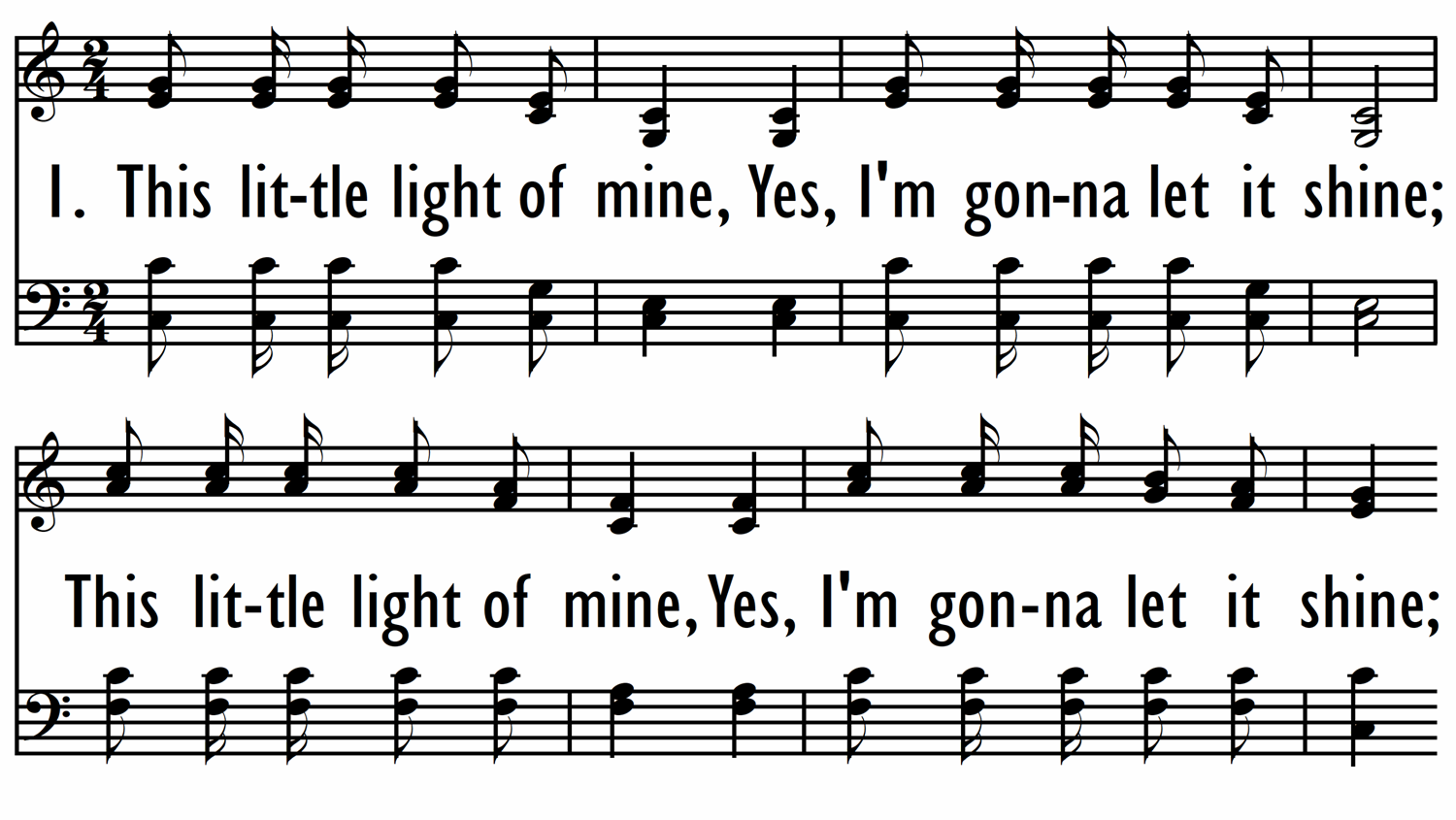

We all know the "This little light of mine, I'm gonna let it shine" part. It's the hook that gets stuck in your head for three days straight. But the actual words to this little light of mine song evolve depending on who is singing and why they are singing it.

The most common version starts with that core declaration of intent. It’s personal. My light. Then, we usually get into the "Hide it under a bushel? No!" verse. This is a direct nod to the Bible—Matthew 5:15, to be specific. It’s about not being ashamed. Then there’s the "Don't let Satan blow it out" line, which adds a bit of spiritual warfare into the mix, though modern secular versions often swap "Satan" for "anyone" or "darkness."

Wait, there’s more.

During the Civil Rights Movement, the lyrics shifted. They had to. When you're marching down a highway in Alabama, the "light" isn't just a metaphor for a good mood. It’s a metaphor for freedom, for voting rights, and for basic human dignity. Verses like "All around the neighborhood" or "Everywhere I go" took on a radical, geographical meaning. It meant the light—the demand for justice—wasn't going to stay confined to a church building. It was going out into the streets.

Why the Simplicity is a Trap

It’s easy to dismiss these lyrics as "kid stuff."

👉 See also: Charlie Charlie Are You Here: Why the Viral Demon Myth Still Creeps Us Out

That’s a mistake.

The simplicity is the point. Short, repetitive sentences make the song impossible to forget and easy to join. If you’re in a crowd of five hundred people and someone starts the first line, everyone knows exactly what to do by the second measure. You don't need a lyric sheet. You don't need a conductor. It’s democratic music.

The Civil Rights Connection and Betty Fikes

If you really want to understand the power of the words to this little light of mine song, you have to look at the Selma movements of the 1960s. This wasn't just a "happy" song back then. It was a tool.

Betty Fikes, often called the "Voice of Selma," used to riff on the lyrics. She’d add verses about the local sheriff or the struggle for the ballot. This turned a simple song into a living, breathing newspaper. It gave people courage when they were facing down dogs and fire hoses. When you sing "I’m gonna let it shine" while looking at a line of armed police, the meaning of "shine" changes from a flicker to a spotlight.

It’s about resilience. It’s about the refusal to be extinguished.

The song’s history is a bit messy, though. While Harry Dixon Loes is the name you’ll see on many copyrights, musicologists like those at the Smithsonian have pointed out that the song’s structure mimics the "sorrow songs" of the enslaved. It’s a "coded" song. Even if Loes wrote the specific melody we hum today, he was tapping into a much older, much darker, and much more powerful reservoir of human endurance.

✨ Don't miss: Cast of Troubled Youth Television Show: Where They Are in 2026

Common Lyric Variations and Their Meanings

Depending on where you grew up, you might have different "standard" verses. Here’s a look at how the prose of the song shifts across different communities:

The Sunday School Version This is the "safe" version. It focuses on the bushel, the neighborhood, and keeping the light bright. It’s pedagogical. It’s meant to teach kids about confidence and faith. "Won't let Satan blow it out" is the big dramatic moment here, usually accompanied by a big "WHOOSH" sound effect and a lot of finger-wagging.

The Social Justice Version In activist circles, the words often change to reflect the specific struggle. "Deep down in my heart" becomes a mantra for internal strength. Sometimes you’ll hear "Even in the jailhouse," which was a very literal reality for many singers in the mid-20th century. The light here represents the truth.

The Secular/Performance Version Artists like Bruce Springsteen or Odetta have taken the song to massive stages. In these contexts, the religious specificities sometimes fade, and the song becomes an anthem of humanism. It’s about the "spark" within every person. It’s less about a divine light and more about the individual’s contribution to the world.

A Quick Word on "The Bushel"

Let’s talk about that bushel. Most kids today have no idea what a bushel is. They think it’s a bush. I’ve seen countless drawings of kids standing next to a shrubbery. But a bushel is a basket. A container. The metaphor is about containment. Are you going to let your potential, your truth, or your joy be boxed up by society or fear?

The answer is a resounding "No!"

🔗 Read more: Cast of Buddy 2024: What Most People Get Wrong

Why We Can’t Stop Singing It

The words to this little light of mine song have an incredible "stickiness." Why? Because they are affirmative. Most songs are about wanting something, losing something, or being sad about something. This song is a declaration of presence.

"I am here. My light is on. I am not hiding."

In an era of digital noise and constant "performative" living, there’s something grounding about a song that just asks you to let your own light shine. It’s not about being the biggest light. It’s not about being a sun or a supernova. It’s just "this little light." Your light. The one you’ve got.

Getting the Lyrics Right (and Making Them Your Own)

If you’re looking to perform or teach this, don't get too hung up on the "official" version. There isn't one. That’s the beauty of folk tradition.

- Start with the core chorus. It’s the anchor.

- Add the "Bushel" verse. It provides the first bit of conflict (the attempt to hide the light).

- Use the "Everywhere I go" verse. This expands the scope of the song from the self to the world.

- Add your own "why." If you’re singing this for a specific cause or person, don't be afraid to improvise. The greatest versions of this song—like those by Fannie Lou Hamer—were heavily improvised.

The impact of this song comes from the conviction of the singer, not the complexity of the rhymes. You don't need a four-octave range. You just need to mean it.

Actionable Takeaway for Musicians and Educators

If you are a teacher or a choir leader, try this: Have your group write their own verses. Ask them what "bushels" are trying to hide their light today. Is it social media? Is it bullying? Is it self-doubt? Replacing the traditional words with these modern "bushels" makes the song hit much harder. It turns a historical artifact into a contemporary tool for empowerment.

The legacy of the words to this little light of mine song isn't found in a dusty hymnal. It’s found in the fact that, nearly a hundred years after it was first written down, we still reach for it whenever the world feels a little too dark. We don't need a complex manifesto. We just need to remind ourselves, and each other, to keep the light on.

Next Steps for Deepening Your Understanding:

- Listen to the SNCC Freedom Singers. Their recordings from the early 60s show the song at its most potent and politically charged.

- Research Harry Dixon Loes. Look into his work at the Moody Bible Institute to see how the song’s "white" evangelical roots eventually merged with the Black gospel tradition.

- Compare versions. Play the version by The Seekers (very folk-pop) against the version by Sam Cooke (soulful and driving) to see how the "light" changes color based on the arrangement.