You know the tune. Even if you think you don't, you do. It’s that jaunty, ragtime-infused melody that seems to live in the permanent muscle memory of American culture. Won't You Come Home Bill Bailey is one of those rare songs that transitioned from a sheet music hit in 1902 to a jazz standard, a cartoon staple, and a karaoke fallback without ever losing its punch.

But here is the thing: the song is actually based on a real person. Most people assume "Bill Bailey" was just a catchy name that fit the meter. He wasn't. He was a real guy from Jackson, Michigan. He was a music teacher. And yes, his wife actually wanted him to come home.

Hughie Cannon, the man who wrote the song, was a talented but troubled ragtime composer. He was hanging out in a saloon—as one did in 1902—when he encountered his friend Bill Bailey. Bill was venting. He’d had a massive fallout with his wife, Sarah, and was effectively locked out. Cannon took that domestic spat and turned it into a goldmine. It’s kind of the 1900s version of a "diss track," except it was surprisingly sympathetic to the wife’s regret.

The Real Story Behind the Lyrics

The lyrics tell a story of a woman—Sarah—regretting her decision to kick Bill out into the "cold, damp night." She’s sitting by the fire, feeling the sting of loneliness, and she offers to pay the rent. That’s a specific detail people often miss. In the original 1902 context, offering to "pay the rent" was a significant gesture of submission and support.

Sarah Bailey actually existed. So did Bill. In fact, after the song became a global phenomenon, the real Bill Bailey reportedly grew quite tired of it. Imagine walking down the street for thirty years and having people shout your own name at you in a syncopated rhythm. He eventually moved to Arkansas to escape the noise, but the song followed him.

🔗 Read more: Donnalou Stevens Older Ladies: Why This Viral Anthem Still Hits Different

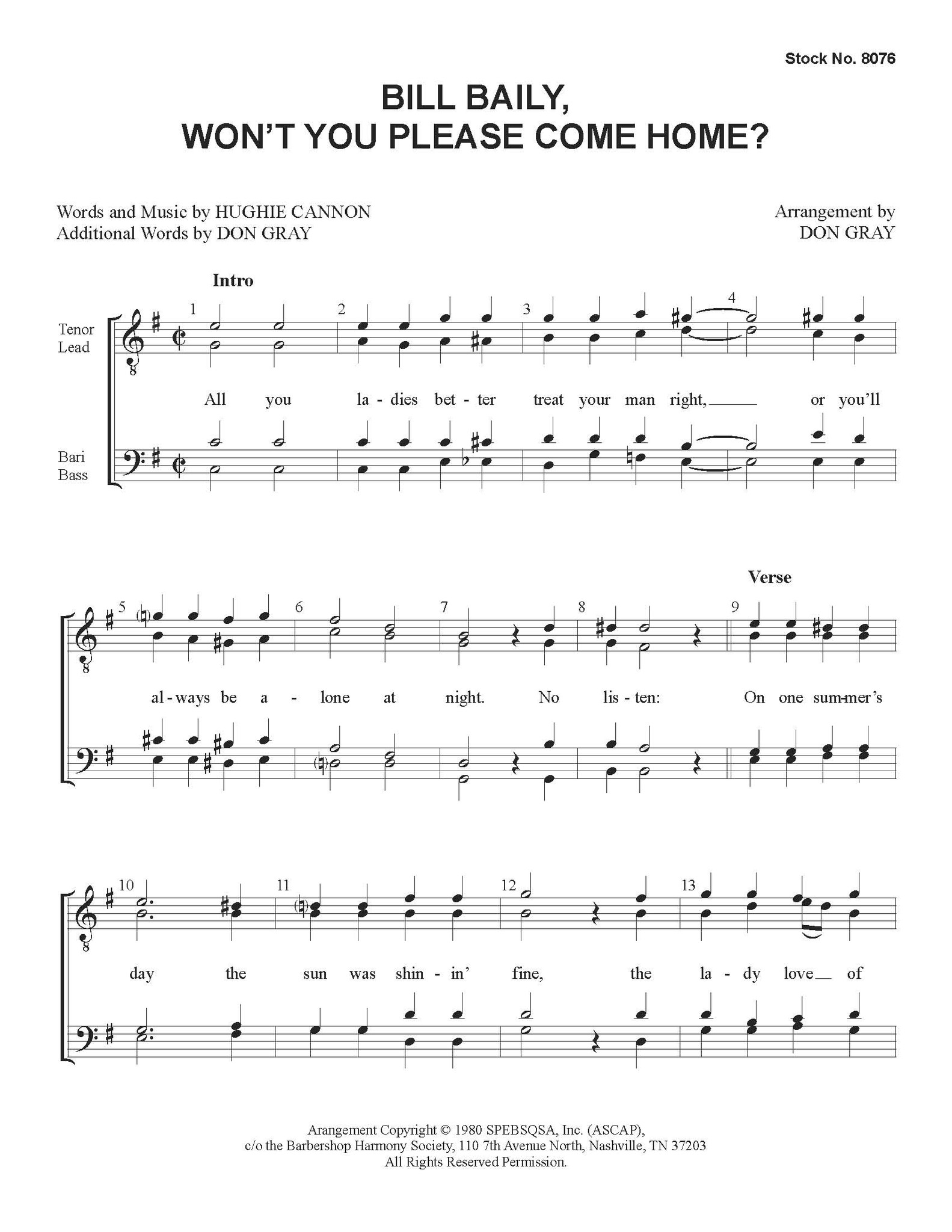

The musical structure is what really makes it stick. Cannon used a classic 32-bar structure, but it’s the chord progression—the way it moves from the tonic to the dominant—that gives it that "circular" feel. It feels like it could loop forever. That is why it became a foundational text for Dixieland jazz.

How it Became a Jazz Essential

When the song first dropped, it was a "coon song," a genre that is, frankly, difficult to discuss today because of its roots in racial stereotypes and minstrelsy. It’s a dark part of American music history. However, the song eventually broke free from those specific origins to become a centerpiece of the New Orleans jazz revival.

- Louis Armstrong gave it a definitive treatment. He infused it with a gravelly, soulful energy that stripped away the vaudeville cheese.

- Ella Fitzgerald took it and turned it into a scat-singing masterclass.

- Bobby Darin arguably recorded the most famous "modern" version in the late 1950s, slicking it up for the Vegas crowd.

The song is incredibly flexible. You can play it as a mournful blues ballad, which emphasizes the regret of the lyrics, or you can blast it at 120 beats per minute as a celebratory stomper. Most people choose the latter. There’s something inherently funny about a man being begged to come home by a woman who "will do the cooking," which hasn't necessarily aged perfectly, but the melody is bulletproof.

Why the Song Won't Die

Why do we still care? Honestly, it’s the "hook." The opening interval of the chorus is a perfect melodic leap. It’s easy to sing, even if you’re tone-deaf.

💡 You might also like: Donna Summer Endless Summer Greatest Hits: What Most People Get Wrong

But there’s also the cultural footprint. If you watched The Simpsons, you’ve heard it. If you’ve ever been to a piano bar, you’ve heard it. It’s part of the "Great American Songbook" not because it’s high art, but because it’s incredibly effective communication. It’s a soap opera condensed into three minutes of ragtime.

The Misconceptions about Hughie Cannon

People often think Cannon made a fortune and lived a lavish life. He didn't. Like many songwriters of the era, he struggled with the transition from the "Big 3" sheet music publishers to the recording era. He died young, around age 35, essentially broke. He sold the rights to the song for a relatively small sum compared to the millions it eventually generated.

It’s a classic, tragic Tin Pan Alley story. The song lives forever; the creator fades away in a boarding house.

Practical Takeaways for Music History Lovers

If you're looking to actually appreciate the depth of Won't You Come Home Bill Bailey, don't just listen to the first version you find on Spotify. There is a progression of style here that mirrors the history of 20th-century music.

📖 Related: Do You Believe in Love: The Song That Almost Ended Huey Lewis and the News

- Seek out the 1902 Arthur Collins recording. It’s scratchy and sounds like it’s coming from another planet, but it’s the closest you’ll get to the original intent.

- Compare the Darin and Armstrong versions. Bobby Darin’s version is about "the show." Armstrong’s version is about "the soul."

- Look for the Jimmy Durante version. He turned it into a piece of comedic theater, proving the song's versatility.

If you're a musician, try playing it in a minor key. It completely changes the narrative. Suddenly, Sarah doesn't sound like she's inviting him back to a party; she sounds like she's mourning a death. That’s the mark of a truly great composition—it can survive being turned inside out.

The next time you hear that familiar "Won't you come home..." refrain, remember the real Bill Bailey in Jackson, Michigan. He was just a guy who had a fight with his wife, and through a stroke of coincidence and a friend with a pen, he became immortal. He never did get that rent money back, though.

To dive deeper into this era of music, investigate the works of Scott Joplin or Ernest Hogan. They provided the rhythmic framework that allowed songs like this to thrive. Understanding the transition from the formal marches of the 1800s to the "ragged" time of the 1900s is the key to understanding why this song feels so modern even now.