It starts with a man trudging through a Bronx downpour. He’s coming from a funeral. He just buried his daughter, Rachele. This isn't a superhero story. There are no capes, no radioactive spiders, and definitely no happy endings waiting on the next page. This is Will Eisner A Contract with God, and if you’ve ever picked up a graphic novel, you owe a debt to this rainy, heartbreaking book.

Honestly, people throw around the term "graphic novel" like it’s always been here. It hasn't. Back in 1978, when this book dropped, the word "comic" meant The Beano or Superman. It meant cheap paper and stories for kids. Eisner wanted to change that. He was tired of the industry’s limitations. He wanted to write about real things: grief, God, poverty, and the crushing weight of living in a 1930s tenement building at 55 Dropsie Avenue.

The Tragedy Behind the Ink

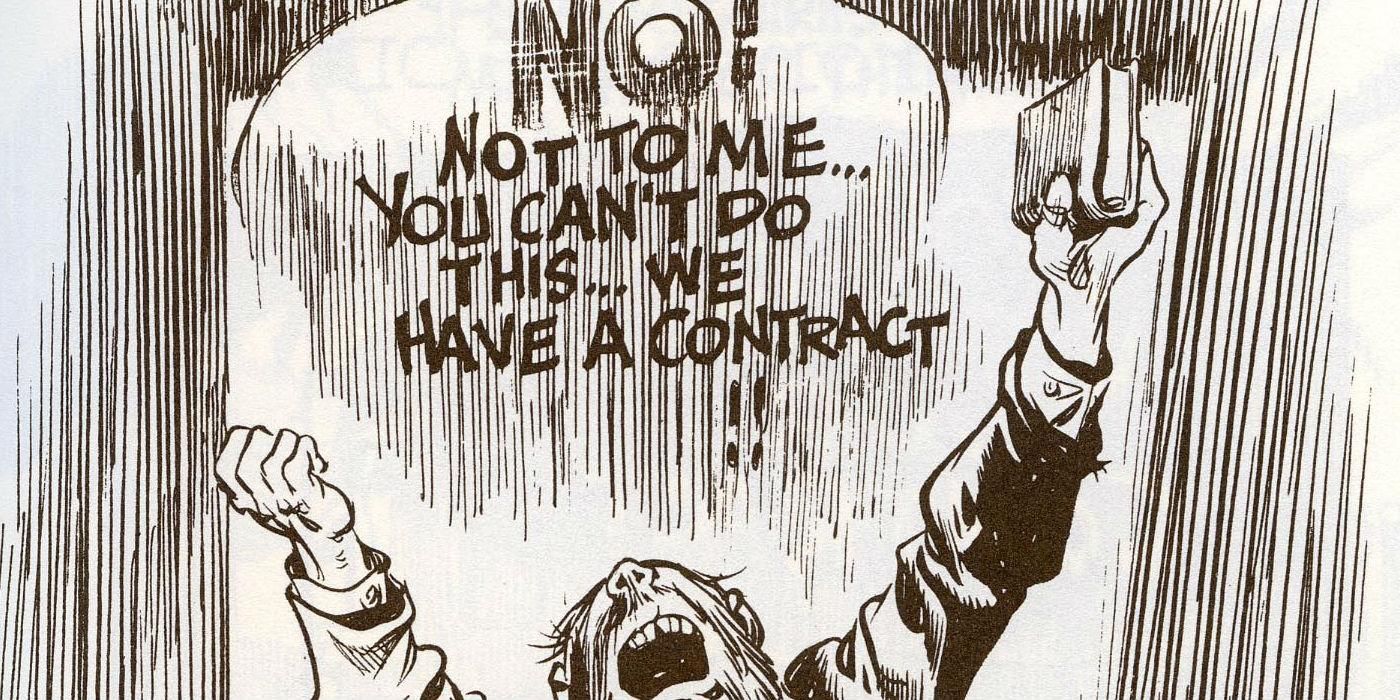

Most people don't know that the first story in the book, the one about Frimme Hersh, is actually a ghost story of sorts. Not the kind with spirits, but the kind where the author is haunted by his own life. Frimme Hersh is a devout man who carves a contract with God on a stone tablet, promising to be a good person if God protects him. When his daughter dies, he feels betrayed. He screams at the sky. He spits on the contract.

🔗 Read more: Why Never Going Back Again Lyrics Still Hit Hard Fifty Years Later

This wasn't just fiction. Will Eisner's own daughter, Alice, died of leukemia when she was only sixteen. He was shattered. For years, he couldn't talk about it. He channeled that raw, ugly anger into Frimme’s story. When you see Frimme raging against the heavens in that rain-soaked alley, you’re seeing Eisner’s own grief on the page. It’s heavy stuff.

Was It Really the First Graphic Novel?

You'll hear people argue about this until they’re blue in the face. Technically, other people had used the term "graphic novel" before. Richard Kyle used it in an essay in 1964. Jack Katz used it. But Eisner was the one who made it stick. He reportedly told his publisher it was a "graphic novel" because he was afraid they’d reject it if he called it a comic book.

It worked.

The book is actually four different stories. They’re all loosely connected by the setting—a fictional Bronx neighborhood.

- A Contract with God: The big one about faith and loss.

- The Street Singer: A dark tale about a guy trying to make it big and the washed-up opera singer who tries to "save" him.

- The Super: A gritty, uncomfortable look at a building superintendent that doesn't shy away from the darker side of human nature.

- Cookalein: A story about city folks heading to the mountains for the summer, full of lust and social climbing.

Why the Art Style Still Holds Up

Eisner didn't use traditional comic panels. You won't find many neat little boxes here. Instead, he used the architecture of the city. Rain pours down the side of the page like a border. Windows frame the characters. The lettering itself feels like it’s part of the world, sometimes big and loud, sometimes small and whimpering.

He used sepia tones in many editions to give it that "old photo" feeling. It’s moody. It’s visceral. You can almost smell the damp hallways of the tenement. He called this "sequential art," a fancy term for storytelling with pictures, but it was really just him trying to prove that you could tell a "serious" story without losing the power of the visual.

The Reality of Dropsie Avenue

The book doesn't sugarcoat anything. It’s got nudity, it’s got violence, and it’s got characters who are just plain mean. In The Super, Mr. Scruggs is a genuinely unpleasant man. Eisner wasn't trying to make heroes; he was trying to make a map of the human soul in a specific time and place.

Some critics back then didn't know what to make of it. Is it a short story collection? A novel? A comic? It’s basically all of the above. It paved the way for books like Maus by Art Spiegelman and Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi. Without Will Eisner A Contract with God, the "literary" comic might never have happened in America.

How to Approach Reading It Today

If you’re going to dive in, don’t expect a quick, fun read. It’s a 20-minute read if you rush, but you shouldn't. You need to sit with it.

- Look at the rain. Eisner is famous for how he draws weather. It’s not just lines; it’s a character.

- Notice the lack of borders. See how the characters' bodies often break out of the "frame." It makes the world feel claustrophobic yet infinite.

- Read the Trilogy. If you like this one, there are two sequels: A Life Force and Dropsie Avenue. They fill out the history of the neighborhood from the 1800s to the modern day.

Actionable Insights for Comic Fans

If you want to understand the roots of modern storytelling, you have to look at how Eisner used "visual metaphors." He didn't just show a man being sad; he showed a man being literally crushed by the shadows of the buildings around him.

- Study the layout. If you're an artist, notice how he guides your eye without using boxes.

- Look for the "silent" moments. Eisner was a master of letting a character's posture do the talking.

- Check out the Centennial Edition. It has a great intro by Scott McCloud that explains why this book changed the "grammar" of comics forever.

The "contract" in the title is something we all have in some way—that feeling that if we’re good, things should go well. Eisner shows us what happens when that contract is broken. It’s a bitter pill, but it’s one of the most honest books ever written in the medium.

💡 You might also like: How to Watch Deal or No Deal Without Losing Your Mind Searching

To truly appreciate the evolution of the form, track down a copy of the "Contract with God Trilogy" collection. It provides the full context of how a single street corner in the Bronx can reflect the entire immigrant experience in America.

Next Steps for Readers:

Check your local library for the 2017 Centennial Edition. It contains corrected art and historical notes that aren't in the original 1978 printing. If you're an aspiring creator, pay close attention to the "Street Singer" chapter; it's a masterclass in using pacing and "beat" to create tension without a single action sequence.