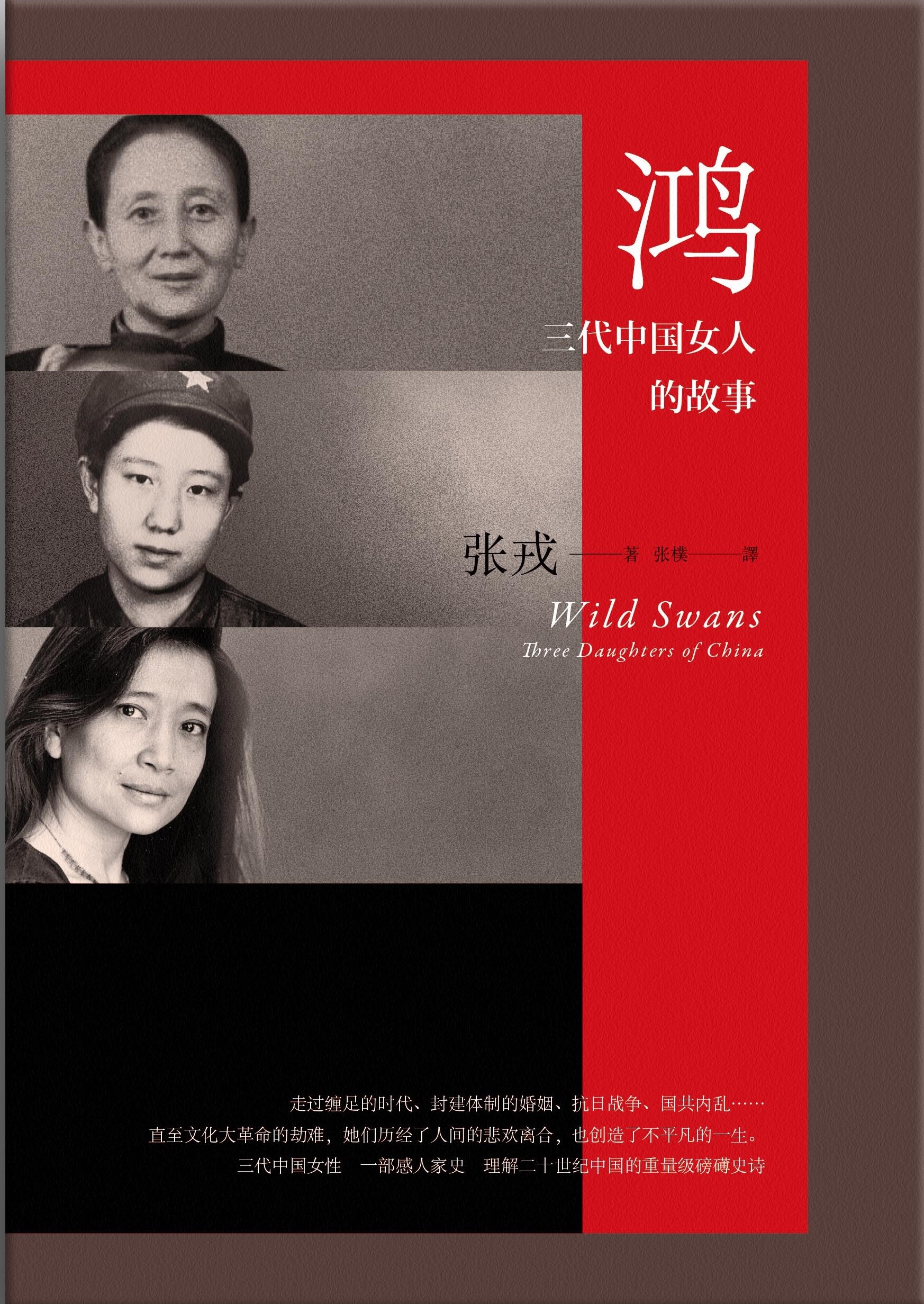

If you’ve ever walked into a used bookstore, you’ve seen it. That white cover, usually a bit yellowed now, featuring three generations of Chinese women. It’s a monolith. Since its release in 1991, Wild Swans by Jung Chang has sold over 15 million copies. That’s a staggering number for a memoir, especially one that doesn't shy away from the brutal, granular details of Maoist China.

People often ask if it’s still relevant. Honestly? It’s more than relevant; it’s basically a decoder ring for understanding how modern China functions today. You can't just look at the gleaming skyscrapers of Shanghai and think you get it. You have to understand the trauma that preceded them.

Chang’s narrative isn’t just a history lesson. It’s a family saga that feels deeply personal, almost uncomfortably so. It traces the life of her grandmother (a warlord's concubine), her mother (a dedicated Communist official), and herself (a Red Guard turned scholar). It’s a 20th-century epic that makes Forrest Gump look like a weekend trip to the grocery store.

The Reality Behind the Hype of Wild Swans by Jung Chang

What most people get wrong about this book is thinking it’s just a "misery memoir." It’s not. While it describes horrific things—binding feet, the famine of the Great Leap Forward, the public denunciations of the Cultural Revolution—it’s actually a study of psychological survival.

Jung Chang’s grandmother, Yu-fang, had her feet bound at age two. Think about that. Two years old. Her feet were broken and crushed so she could eventually be gifted to General Yang Sen. This wasn’t some ancient, distant history; it was the starting point for a family that would eventually witness the birth of the People’s Republic.

The book hits hard because of the contrast. You see the transition from the "Old World" of concubines and silk to the "New World" of drab Mao suits and ideological purity.

✨ Don't miss: Am I Gay Buzzfeed Quizzes and the Quest for Identity Online

Why the Mother’s Story is the Real Heart of the Book

While the grandmother’s story is haunting, the middle section—focusing on Chang’s mother, Bao Qin—is where the political meat is. Bao Qin and her husband were true believers. They were high-ranking officials who genuinely thought they were building a utopia.

Then the party turned on them.

The tragedy of Wild Swans by Jung Chang is watching the revolution eat its own children. Chang’s father, a man of immense integrity, was eventually driven to a mental breakdown by the very system he helped create. It’s a chilling reminder of how quickly "the cause" can become a meat grinder for the people who care about it most.

Life as a Red Guard: Jung Chang’s Own Perspective

When we talk about the Cultural Revolution, we often view it through a wide-angle lens. We see the mass rallies. We see the Red Books. But Chang gives us the POV of a teenager who was actually there.

She was a Red Guard. Briefly.

🔗 Read more: Easy recipes dinner for two: Why you are probably overcomplicating date night

She admits to the fervor. She describes the weird, almost religious ecstasy of seeing Mao Zedong in person. But then she describes the reality of being sent to the countryside to work as a "barefoot doctor" and a peasant.

- She saw the poverty.

- She saw the futility of the backyard furnaces.

- She realized the "paradise" was a lie.

This isn't a dry academic text by someone like Frank Dikötter (who is brilliant, don't get me wrong). It’s the account of someone who felt the blisters on her hands.

The Ban That Still Stands

It’s a bit of a "fun fact" that isn't very fun: Wild Swans by Jung Chang is still banned in mainland China. You can find it in Hong Kong (though that’s getting harder) and Taiwan, but in the PRC? It’s a ghost.

Why? Because it humanizes the figures that the state wants to keep as icons. It shows Mao not as a god, but as a man whose policies resulted in tens of millions of deaths. Chang doesn't hold back. In her later biography of Mao, she went even further, but Wild Swans is where the emotional damage is most evident.

Critics sometimes argue that Chang is too biased. They say she focuses too much on the suffering and ignores the industrial gains of the era. But how do you stay "unbiased" when your father was tortured and your education was stolen? The book is a memoir, not a census report. Its power lies in its subjectivity.

💡 You might also like: How is gum made? The sticky truth about what you are actually chewing

How to Read Wild Swans Without Getting Overwhelmed

Let’s be real: this book is long. It’s dense. It’s heavy. If you’re going to dive in, you need a strategy.

First, don't try to memorize every political movement. The names of the campaigns—the "Three-Antis," the "Five-Antis," the "Hundred Flowers"—can get confusing. Focus on the family. Follow their emotional arc. The politics will make sense through their eyes.

Second, pay attention to the small details. Chang is a master of the "micro-horror." She describes how people had to hide their emotions because even a "wrong" facial expression could get you reported to the authorities. That kind of psychological pressure is what stays with you long after you finish the last page.

Actionable Insights for the Modern Reader

If you’ve finished the book or are planning to, here is how to apply that knowledge to the world we live in now:

- Look for the Echoes: When you see modern "cancel culture" or online dogpiling, compare the mechanics to the "Struggle Sessions" described in the book. The scale is different, but the human impulse to conform and punish dissent is eerily similar.

- Contextualize Modern China: Understand that the current leadership in China grew up during the events of Wild Swans. Their obsession with "stability" makes a lot more sense when you realize they lived through total chaos.

- Question the Narrative: Chang’s book is a testament to the power of the individual voice against a state-mandated story. It encourages you to look for the "unofficial" histories in any culture.

Wild Swans by Jung Chang isn't just a book about China. It’s a book about what happens when ideology is placed above humanity. It’s about the resilience of women in a world designed to break them.

If you want to understand the 21st century, you have to start with the 20th. And there is no better starting point than this family. Read it for the history, sure. But stay for the sisters, the mothers, and the grandmothers who managed to keep their souls intact when everything else was falling apart.

To get the most out of your reading, pair it with some visual history. Look up archival footage of the 1966 rallies in Tiananmen Square. Seeing the sea of Red Books makes Chang's descriptions of the "Red Sea" period feel visceral. Then, look at photos of foot-binding. It’s a hard look, but it anchors the beginning of the book in a physical reality that's difficult to wrap your head around otherwise. You might also consider reading Mao: The Unknown Story by Chang and Jon Halliday afterward to see how her personal experiences translated into her later, more controversial historical research. This provides a full picture of her evolution from a victim of the system to one of its most vocal chroniclers.