On July 5, 1852, Frederick Douglass stood before the Ladies' Anti-Slavery Society in Rochester, New York. He wasn't there to give a standard patriotic toast. Honestly, he was there to tear the mask off American hypocrisy. Imagine the scene: a room full of white abolitionists expecting a "thank you" for their hard work, and instead, they get a man who had escaped the literal chains of Maryland telling them their celebration is a sham. It was brutal. It was brilliant.

When we talk about What to the Slave is the Fourth of July, we aren't just looking at a dusty old transcript from the 19th century. We are looking at a rhetorical bomb. Douglass didn't just ask a question; he redefined what it meant to be a citizen in a country that claimed "all men are created equal" while simultaneously auctioning off human beings like cattle in the town square.

The Raw Disconnect of 1852

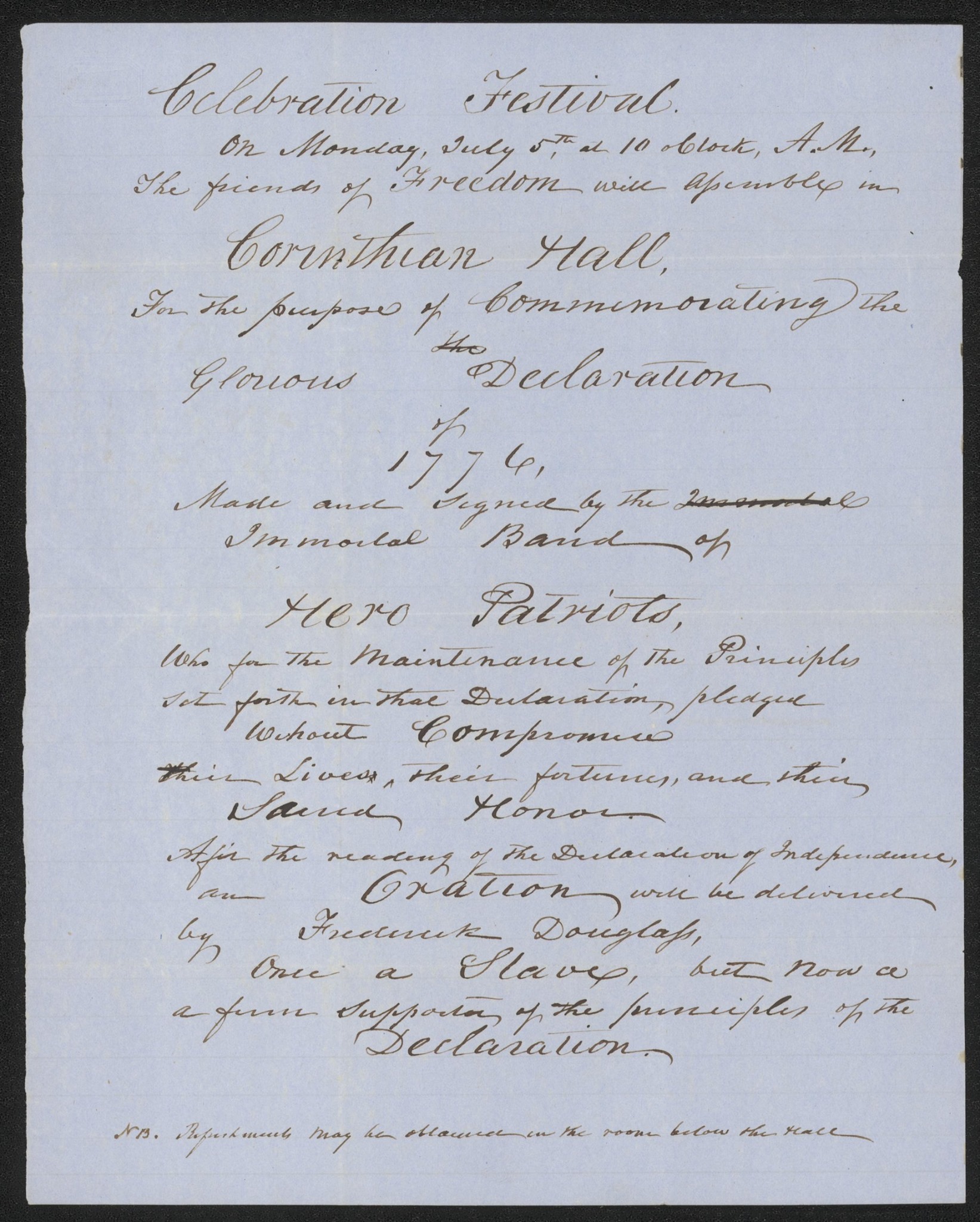

The atmosphere in Corinthian Hall that day must have been electric. Douglass started out soft. He spoke about the greatness of the Founding Fathers. He acknowledged their bravery. But then he pivoted. Hard. He shifted from "your" national greatness to "my" national mourning.

He didn't say "our" Fourth of July.

He made it very clear that he was an outsider looking in. For the enslaved population, the fireworks weren't signs of liberty; they were reminders of the freedom they didn't have. It’s kinda wild when you think about the guts it took to stand up in front of a crowd of supporters and tell them their joy was an offense to God and man. He called the Fourth of July a "thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages." Those aren't polite words. They were meant to draw blood.

He hammered home the irony of a "Christian" nation that protected the internal slave trade. He described the "man-stealer" and the "flesh-monger" walking the same streets as the pious church-goer. This wasn't just a political speech. It was a moral indictment.

Why the Speech Hits Differently in the 2020s

You’ve probably seen clips of Douglass's descendants reading the speech on social media every July. It goes viral for a reason. The core of What to the Slave is the Fourth of July is the tension between American ideals and American reality. We still live in that tension.

🔗 Read more: The Faces Leopard Eating Meme: Why People Still Love Watching Regret in Real Time

Critics often argue that Douglass was too harsh. But was he? In 1852, the Fugitive Slave Act was in full effect. This meant that even in "free" states like New York, a Black person could be snatched off the street and dragged into the South based on nothing but a white person's word. There was no "safe" space. When Douglass spoke, he was legally a fugitive himself for a large chunk of his life, though his freedom had been purchased by British friends a few years prior. He knew the stakes.

The speech addresses the "immeasurable distance" between the two groups. That distance hasn't totally closed. When we look at modern debates over voting rights, criminal justice, or even how history is taught in schools, we are seeing the echoes of Douglass’s frustration. He was basically saying: "Don't tell me about your liberty while you're standing on my neck." It’s a message that refuses to die because the conditions that created it haven't fully vanished.

The Scorching Irony of the Bible

Douglass was deeply religious, but he had no patience for the "slave-holding Christianity" of the South. He famously said that he loved the "pure, peaceable, and impartial Christianity of Christ," but he hated the corrupt version that used the Bible to justify the whip.

In the speech, he quotes Psalm 137. This is the part where the captives are asked to sing "one of the songs of Zion" while in exile in Babylon. "How shall we sing the Lord’s song in a strange land?" he asks. It’s a devastating parallel. He’s comparing the American South to Babylon and the enslaved people to the Israelites. For a 19th-century audience, this was heavy-duty stuff. He was using their own sacred book to show them they were the villains of the story.

Deconstructing the Rhetorical Genius

If you're a student of public speaking, this is the gold standard. Douglass uses a technique called paralipsis—where you say you aren't going to talk about something while you're actually talking about it. He says he doesn't need to prove that slaves are men. Why? Because the laws already prove it.

Think about it: Virginia had seventy-two crimes that carried the death penalty for a Black man, but only two for a white man. If the slave wasn't a "moral, intellectual, and responsible being," why have laws for him? You don't pass laws for a horse or an ox. By the very act of punishing the enslaved, the government admitted they were human. It's a logical trap that nobody could wiggle out of.

💡 You might also like: Whos Winning The Election Rn Polls: The January 2026 Reality Check

He also destroys the idea that slavery was a "necessary evil." He calls it what it was: a "system of sheer piracy."

Common Misconceptions About the Speech

A lot of people think Douglass gave this speech on July 4th. He didn't. He was invited to speak on the 4th, but he refused. He chose the 5th.

That small choice is huge.

It was a deliberate snub. It signaled that he would not participate in the pageantry of the 4th. He wanted to wait until the hangovers kicked in and the parade was over to deliver the truth.

Another misconception is that he hated America. If you read the whole thing—and it’s long, usually taking about an hour to perform—he actually ends on a somewhat hopeful note. He mentions that "the arm of the Lord is not shortened" and that the world is becoming more connected. He believed the "genius of American Institutions" would eventually have to reconcile with the "declaration of independence." He wasn't trying to burn the house down; he was trying to force the owners to live up to the deed.

What Most People Miss: The Global Context

Douglass wasn't just talking to Rochester. He was talking to the world. In 1852, the United States was trying to establish itself as a moral leader on the world stage. Douglass pointed out that the rest of the world looked at America with disgust. He mentioned how the "despots of Europe" used American slavery as a way to mock democracy.

📖 Related: Who Has Trump Pardoned So Far: What Really Happened with the 47th President's List

"You boast of your love of liberty," he shouted, while the "clanking of your infernal chains" could be heard across the Atlantic.

He was using international pressure as a lever. He knew that the only way to change the American mind was to embarrass the American ego. He basically told them they were the laughingstock of the civilized world.

The Impact Today: Actionable Insights

So, what do we do with this? Reading What to the Slave is the Fourth of July shouldn't just be an exercise in historical guilt. It’s a blueprint for modern advocacy and self-reflection.

First, embrace the discomfort. Douglass didn't write this to make people feel good. If a piece of history makes you uncomfortable, that’s usually where the most growth happens. Instead of shying away from the darker parts of the American story, lean into them. Understanding the "immeasurable distance" Douglass spoke of helps us see where that distance still exists today.

Second, check the "veil." Douglass talked about the "thin veil" of American patriotism. We should ask ourselves: what are we covering up today with slogans and flags? Are we using patriotic rhetoric to avoid dealing with uncomfortable truths about poverty, healthcare, or inequality? True patriotism, in the Douglass sense, is the courage to call your country to account.

Third, use your voice. Douglass was a master of the "scorching irony." You don't have to be a world-class orator to speak up against injustice, but you do have to be willing to be unpopular. Douglass lost friends and supporters because he wouldn't tone it down.

Next Steps for Deeper Understanding

If you want to really get into the head of Frederick Douglass, don't just read the "best of" snippets.

- Read the Full Text: Most people only know the middle section. Read the beginning where he praises the Founders, and the end where he talks about the "inevitable" fall of slavery. It gives the speech a much more complex arc.

- Watch a Performance: Hearing the words spoken aloud changes the experience. James Earl Jones and Ossie Davis have famous recordings, but look for newer versions by actors like Daveed Diggs or David Harewood. The rhythm of the speech is meant for the ear, not just the eye.

- Compare with the "Oration in Memory of Abraham Lincoln": Given twenty-four years later, this speech shows how Douglass's view of the American project evolved after the Civil War. It’s a fascinating look at how a radical activist deals with the messy reality of political progress.

- Visit the Site: If you’re ever in Rochester, visit the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site. Standing near where he lived and worked gives a tangible sense of the environment that birthed such a fierce intellect.

Douglass knew that "power concedes nothing without a demand." He made that demand on a hot July day in 1852, and we are still answering it. The Fourth of July will always be a complicated holiday for many, but as long as we keep asking the questions Douglass asked, there's a chance we might eventually find the right answers.