Blood sugar isn't just a number on a plastic meter. It’s fuel. When that fuel drops, things get weird fast. You might feel a little shaky or suddenly realize you’ve been staring at the same email for ten minutes without reading a single word. Most doctors and organizations like the American Diabetes Association (ADA) will tell you that the magic number is 70 mg/dL. Below that? You're officially in the hypoglycemia zone. But "dangerous" is a relative term. For some, 65 mg/dL is a minor annoyance; for others, it’s an emergency room visit in the making. Understanding what is a dangerous low level of blood sugar requires looking past the standard guidelines and into how the human brain reacts when the lights start to flicker.

Low sugar is a thief. It steals your coordination, your temper, and eventually, your consciousness.

The Three Tiers of Trouble

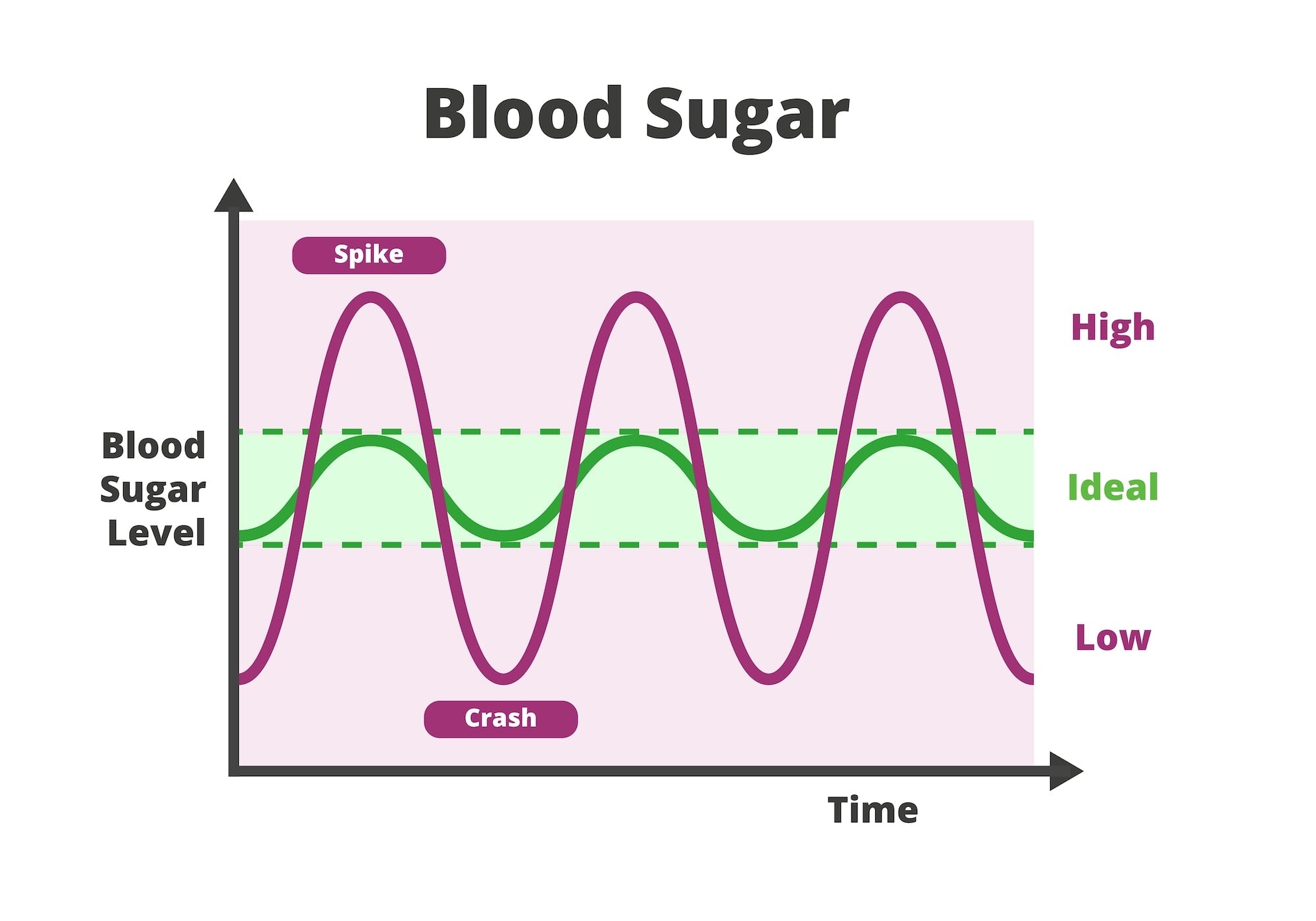

Medical professionals usually break down hypoglycemia into three distinct levels. Level 1 is that 70 mg/dL threshold. It’s a warning shot. You might feel hungry or slightly "off." Level 2 is more aggressive, usually defined as anything below 54 mg/dL. This is where the brain starts screaming for glucose. Level 3 is the "danger zone" regardless of the actual number on the screen. This is clinical hypoglycemia where you can't function. You need someone else to help you because you’re either too confused to eat or you’ve lost consciousness.

Numbers matter, but symptoms matter more.

I’ve talked to people who felt perfectly fine at 55 mg/dL because their bodies had grown used to being low—a condition called hypoglycemia unawareness. This is actually one of the most dangerous scenarios possible. If your body stops sending the "shaky and sweaty" signals, you might slide straight from feeling "fine" into a seizure. That’s why the definition of a dangerous low is often dictated by your personal history with the condition rather than a universal chart on a wall.

Why 54 mg/dL is the Line in the Sand

If you’re looking for a hard answer on what is a dangerous low level of blood sugar, 54 mg/dL is usually where the red alert starts. At this stage, the autonomic nervous system is in full-blown panic. Adrenaline spikes. Your heart starts hammering against your ribs like a trapped bird.

Why 54? Because research, including studies published in The Lancet, shows that below this point, cognitive function begins to deteriorate significantly. You lose the ability to perform complex tasks. Driving a car becomes as dangerous as driving under the influence of heavy alcohol. The brain consumes about 20% of the body's glucose despite only being 2% of its weight. When that supply line is cut, the "checks and balances" part of your brain—the prefrontal cortex—is the first thing to go dark. You become impulsive. You might get angry at a loved one for no reason.

👉 See also: What Really Happened When a Mom Gives Son Viagra: The Real Story and Medical Risks

It’s scary.

The Nighttime Threat: Dead in Bed Syndrome

There is a somber term in the type 1 diabetes community: "Dead in Bed Syndrome." It sounds like a horror movie title, but it refers to the very real risk of a sudden, fatal hypoglycemic event during sleep. Most of these cases involve young people. While the exact pathology is still debated, many experts believe a severe low during the night can trigger a fatal cardiac arrhythmia.

When you're asleep, you can't feel the shakes. You can't feel the sweats. If your blood sugar hits a dangerous low while you’re dreaming, your only defense is your body’s internal counter-regulatory hormones, like glucagon and cortisol. But for many people with long-term diabetes, those backup systems are broken.

Modern Tech to the Rescue

We aren't in the dark ages anymore. Continuous Glucose Monitors (CGMs) like the Dexcom G7 or the FreeStyle Libre 3 have changed the game. These devices use a tiny sensor under the skin to check glucose levels every few minutes. They don't just tell you the number; they tell you the trend.

Seeing a "75" with a straight arrow is fine. Seeing a "75" with two arrows pointing straight down is an impending disaster.

The Rule of 15: How to Fight Back

Treating a low isn't about eating a Thanksgiving dinner. It’s about precision. The standard protocol is the "Rule of 15."

✨ Don't miss: Understanding BD Veritor Covid Test Results: What the Lines Actually Mean

- Consume 15 grams of fast-acting carbs.

- Wait 15 minutes.

- Check again.

If you're still below 70, repeat.

What counts as 15 grams? Think small. Half a cup of fruit juice. A tablespoon of honey. Four glucose tablets. The mistake people make is the "panic eat." You feel like you're dying, so you eat an entire sleeve of cookies and a bowl of cereal. Twenty minutes later, your sugar is 300 mg/dL, and you feel like garbage for a different reason.

When Food Isn't Enough

If someone is in a Level 3 low, you cannot give them food. They might choke. This is where Glucagon comes in. In the old days, this involved a "red kit" with a needle and a vial that you had to mix manually while panicking. It was a nightmare.

Today, we have Baqsimi, which is a nasal powder. You just stick it up the person's nose and spray. There’s also Gvoke, which comes in a pre-filled autoinjector like an EpiPen. These are literal lifesavers. If you have a history of frequent lows, you basically need to have one of these in your bag, your nightstand, and probably your car.

The Nuance of "Low" in Non-Diabetics

Can you have a dangerous low if you don't have diabetes? Yes, though it’s rarer. This is usually reactive hypoglycemia. It happens when your pancreas overreacts to a high-carb meal and dumps way too much insulin into your system. You eat a giant stack of pancakes, and two hours later, you’re sweating and dizzy.

There are also more serious causes:

🔗 Read more: Thinking of a bleaching kit for anus? What you actually need to know before buying

- Insulinomas (rare tumors on the pancreas).

- Severe liver disease.

- Addision’s disease.

- Excessive alcohol consumption on an empty stomach (alcohol blocks the liver from releasing stored glucose).

If you aren't on insulin but you’re regularly hitting 60 mg/dL, something is wrong. You need a workup. It’s not just "hunger." It’s a systemic failure to maintain homeostasis.

The Long-Term Cost of Lows

Falling down or crashing a car is an immediate danger. But there’s a slower, more insidious danger to frequent low blood sugar. Recent studies have suggested a link between repeated severe hypoglycemia and an increased risk of dementia later in life.

The brain doesn't like being starved. Every time you hit a "dangerous low," you're essentially subjecting your neurons to a localized famine. Over decades, that damage adds up. It can affect memory, processing speed, and emotional regulation. This is why the "tight control" obsession of the 1990s has shifted. Doctors used to want your A1c as low as possible. Now, they want it low without the lows. They call this "Time in Range."

Staying between 70 and 180 mg/dL is the goal. If you have to spend half your day at 250 mg/dL just to avoid a 50 mg/dL, that’s a problem too, but the low is the one that will kill you today.

Actionable Steps for Safety

You can't just hope you won't go low. You need a system.

- Check the Trend: If you use a CGM, set your "Low Alert" to 80 mg/dL instead of 70. This gives you a 10-point buffer to treat the drop before it becomes a crisis.

- The Nightstand Stash: Keep glucose tabs or a juice box within arm's reach of your bed. Don't rely on being able to walk to the kitchen. When your sugar is 45, the hallway can feel like a five-mile hike.

- Wear a MedicAlert: It feels old-school, but if you're found unconscious, a paramedic needs to know if they're dealing with a stroke, a heart attack, or a low. A simple bracelet saves time.

- Educate Your Circle: Your "low" personality might be mean or stubborn. Tell your friends and family: "If I'm acting like a jerk and refusing to eat, make me eat anyway."

- Review Your Basal: If you’re going low at the same time every day, your insulin dosages are likely wrong. Your needs change with stress, exercise, and age.

Dangerous levels of blood sugar aren't just a threat to your health; they are a threat to your autonomy. Taking control means acknowledging that the "70" rule is just a starting point. Your personal safety zone might be higher, especially if you live alone or have other health complications. Keep the fast-acting carbs close, keep your sensors calibrated, and never ignore that first tiny tremor in your hands. It's your body's way of saying the tank is empty.