It's that heavy, damp feeling in the air. You wake up, look at the window, and the sky isn't just gray—it’s a bruised, oppressive charcoal. Your joints might ache. Maybe the dog is acting a little weirder than usual. Most people just call it "bad weather," but if you look at a barometer, you’re actually seeing weather with low pressure in action.

Low pressure systems, or cyclones as meteorologists like Dr. Marshall Shepherd often call them, are basically the atmosphere’s way of throwing a tantrum. It’s not just "rain." It’s a complex physical process involving rising air, converging winds, and a whole lot of thermodynamics that dictate whether you’re going to need an umbrella or a basement.

What is Weather With Low Pressure, Honestly?

Think of the atmosphere like a giant, invisible ocean. In some places, that ocean is deep and heavy—that’s high pressure. In others, the "water" is thinner. Air, like water, hates being uneven. It wants to rush into those thin spots to fill the gap.

In a low-pressure area, the air is lighter than the air surrounding it. Because it's lighter, it starts to rise. This is the golden rule of meteorology: rising air cools, and cooling air condenses into clouds. If you have high pressure, the air is sinking. Sinking air warms up and dries out, which is why high pressure usually means blue skies and sun. But weather with low pressure? It’s the exact opposite. It’s the vacuum cleaner of the sky, sucking up moisture and heat from the ground and shoving it into the upper atmosphere where it turns into a mess.

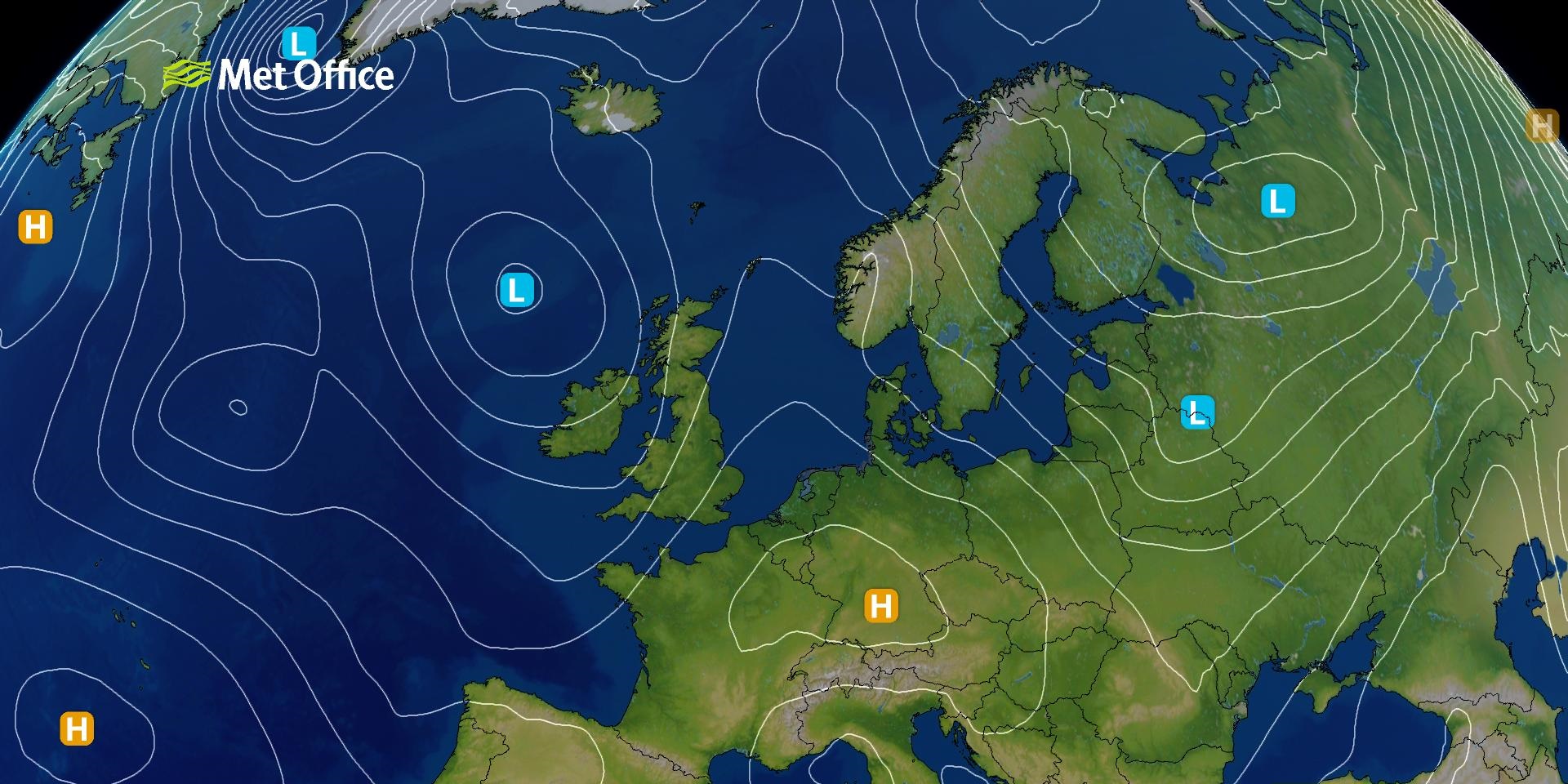

The "L" on the Map

You’ve seen it on the news. A big red "L." It looks simple, but that letter represents a swirling vortex. Because of the Coriolis effect—a fancy way of saying the Earth spins—this air doesn't just rush straight into the center. It spins. In the Northern Hemisphere, it spins counter-clockwise. This rotation is why a low-pressure system moving up the East Coast of the U.S. (a Nor'easter) pulls cold air down from Canada and wet air off the Atlantic, creating a snowy nightmare.

Why Your Body Feels the Drop

Have you ever wondered why your grandma can "feel" a storm coming in her knees? She's not psychic. She’s a biological barometer.

When weather with low pressure moves in, the weight of the air pressing against your body literally decreases. This allows the tissues in your body—especially around your joints—to expand slightly. If you have arthritis or old sports injuries, that expansion puts pressure on your nerves. A study published in the journal Pain actually looked at this, finding that changes in barometric pressure and temperature can indeed trigger increased joint pain. It's not in your head. It's physics acting on your cartilage.

- Sinus Headaches: The air inside your sinus cavities stays at the old "high" pressure while the outside air drops. That pressure differential is what causes that pounding behind your eyes.

- Blood Pressure: Some studies suggest your blood pressure might actually drop slightly when the atmospheric pressure does, which is why some people feel lethargic or "heavy" on rainy days.

The Anatomy of a Low Pressure Storm

Not all lows are created equal. You’ve got your garden-variety rainy afternoon, and then you’ve got "bomb cyclones."

A bomb cyclone happens through a process called explosive cyclogenesis. To qualify, the central pressure of a storm has to drop at least 24 millibars in 24 hours. That is a massive, sudden change. When the pressure drops that fast, the wind goes absolutely nuts trying to fill the void. This happened famously during the 1993 "Storm of the Century."

Low pressure is also the heart of every hurricane. The lower the pressure in the "eye," the stronger the winds. In 1979, Typhoon Tip reached a record low pressure of 870 hPa. For context, standard sea-level pressure is about 1013.25 hPa. At 870, the atmosphere is basically screaming.

Clouds and Convection

Inside these systems, you get different types of "lifting."

- Frontal Lifting: This is when a cold air mass hits a warm one. The warm air is forced up over the cold air like a ramp. Result? Massive thunderheads.

- Orographic Lifting: This is when the wind hits a mountain. The mountain forces the air up, the air cools, and you get dumped on. If you live in Seattle, you know this well.

- Convective Lifting: This is just the sun heating the ground until the air bubbles up like a pot of boiling water.

How to Read the Signs Without an App

Long before we had satellites and smartphones, people had to read the weather with low pressure through observation. You can still do this.

Watch the smoke from a chimney. If it rises straight up, the pressure is high and the air is stable. If the smoke curls downward or hangs low to the ground, the pressure is low. The air is literally too heavy for the smoke to rise through.

✨ Don't miss: Living at 496 Bluebird Canyon Dr Laguna Beach CA 92651: What Most People Get Wrong About Living in the Canyon

Also, look at the clouds. High, wispy "mare's tails" (cirrus clouds) often show up 24 to 48 hours before a low-pressure system arrives. They are the scouts. If they start to thicken into a "mackerel sky" (altocumulus), the low is getting closer. When the clouds get low and featureless like a gray blanket (stratus), you’re already in it.

The Misconceptions About Rain

People think rain is the "cause" of low pressure. It's the other way around.

The rain is just a symptom of the rising air. In fact, you can have a low-pressure system with no rain at all if the air is too dry. We call these "dry lows" or "heat lows," often found in deserts like the Southwest U.S. during the summer. They don't bring rain, but they bring massive wind and dust storms because the pressure gradient is still there, pulling air in from miles away.

The Role of the Jet Stream

Low-pressure systems don't just wander aimlessly. They are steered by the jet stream—a river of fast-moving air high in the atmosphere. Think of the jet stream like a conveyor belt. If the belt is moving fast and has big "waves" in it, it's going to hurl one low-pressure system after another at you. This is why you'll sometimes have a week where it rains every single Tuesday for a month.

Managing Your Life Around Low Pressure

If you know weather with low pressure is coming, you can actually prepare for it beyond just grabbing a coat.

Since low pressure usually means more humidity and less stable air, it’s a terrible time for certain activities. Don't paint your house. The paint won't dry correctly because the air is already saturated. Don't try to bake a delicate soufflé; the lower air pressure can cause it to rise too fast and then collapse.

On the flip side, it’s a great time for fishing. Many anglers swear that fish bite more right before a cold front (a low-pressure boundary) moves through. The theory is that fish can sense the pressure change in their swim bladders and feed heavily before the storm makes the water too murky or turbulent.

[Image showing the movement of a cold front and warm front within a low pressure system]

Actionable Steps for the Next Pressure Drop

Stop letting the weather surprise you. When the forecast mentions a "trough" or a "developing low," here is how to handle it:

- Hydrate Early: If you're prone to barometric headaches, start drinking extra water before the pressure bottoms out. Dehydration makes the "pressure head" feeling significantly worse.

- Seal the Gaps: Low pressure literally sucks air out of your house. If you have drafty windows, you’ll feel it more during these storms. Use it as a diagnostic tool to see where your home is losing energy.

- Adjust Your Workout: If your joints are screaming, swap the high-impact run for swimming or yoga. The buoyancy helps offset that heavy feeling in your limbs.

- Check Your Tires: When the pressure in the atmosphere changes, the "apparent" pressure in your tires can fluctuate. Sudden drops in temperature—which often follow a low-pressure front—will definitely cause your "low tire pressure" light to flick on.

The atmosphere is a heavy, moving thing. We live at the bottom of it, and we are subject to its weight every second. Understanding weather with low pressure isn't just for pilots or sailors; it's for anyone who wants to know why they're tired, why their head hurts, or why their picnic just got rained out. Next time you see that red "L" on the map, don't just shrug. Look at the clouds, watch the wind direction, and realize you're watching a massive planetary engine at work.