You're standing on the beach in the Outer Banks, watching the horizon turn a bruised shade of purple. You pull out your phone, open a weather app, and look for that familiar green and red blob moving toward you. It’s easy to assume there’s a giant spinning dish somewhere out in the waves sending that data back to your screen. Honestly, that’s not how it works at all. Most people don’t realize that weather radar for the Atlantic Ocean is actually a massive logistical headache that relies more on outer space than it does on anything in the water.

The Atlantic is a desert. For data, anyway.

If you’re on land, you’re covered by the NEXRAD (Next-Generation Radar) network. These are those giant white soccer-ball-looking domes you see near airports or on hillsides. They have a range of about 143 miles for clear air and maybe 286 miles for tracking significant storms. Once you get a few hundred miles off the coast of Florida or New Jersey, you're essentially flying blind if you're relying on traditional ground-based pulses. This gap is what meteorologists call the "radar void." It’s a terrifying thought when you realize that’s exactly where the world's most dangerous hurricanes gather their strength.

The Physical Limits of Ground-Based Weather Radar for the Atlantic Ocean

Physics is a bit of a jerk when it comes to the curve of the Earth. Even if we built a radar tower right on the shoreline, the beam travels in a straight line while the planet curves away beneath it. By the time that beam gets 200 miles out, it’s shooting way over the top of the storm clouds. You might see the very wispy tops of a thunderhead, but you’re missing the "engine room" of the storm near the water’s surface.

Because of this, we can't just put more towers on the coast and hope to see what's happening near the Cape Verde islands. We’ve tried some wild stuff over the years. We used to have "Texas Towers," which were basically converted oil rigs used for radar, but they were dangerous and prone to collapsing during—you guessed it—major Atlantic storms. The most famous one, Texas Tower 4, went down in 1961, taking 28 souls with it. Since then, we’ve mostly given up on putting permanent heavy radar structures in the deep blue.

So, how do we actually know what’s coming?

📖 Related: Brain Machine Interface: What Most People Get Wrong About Merging With Computers

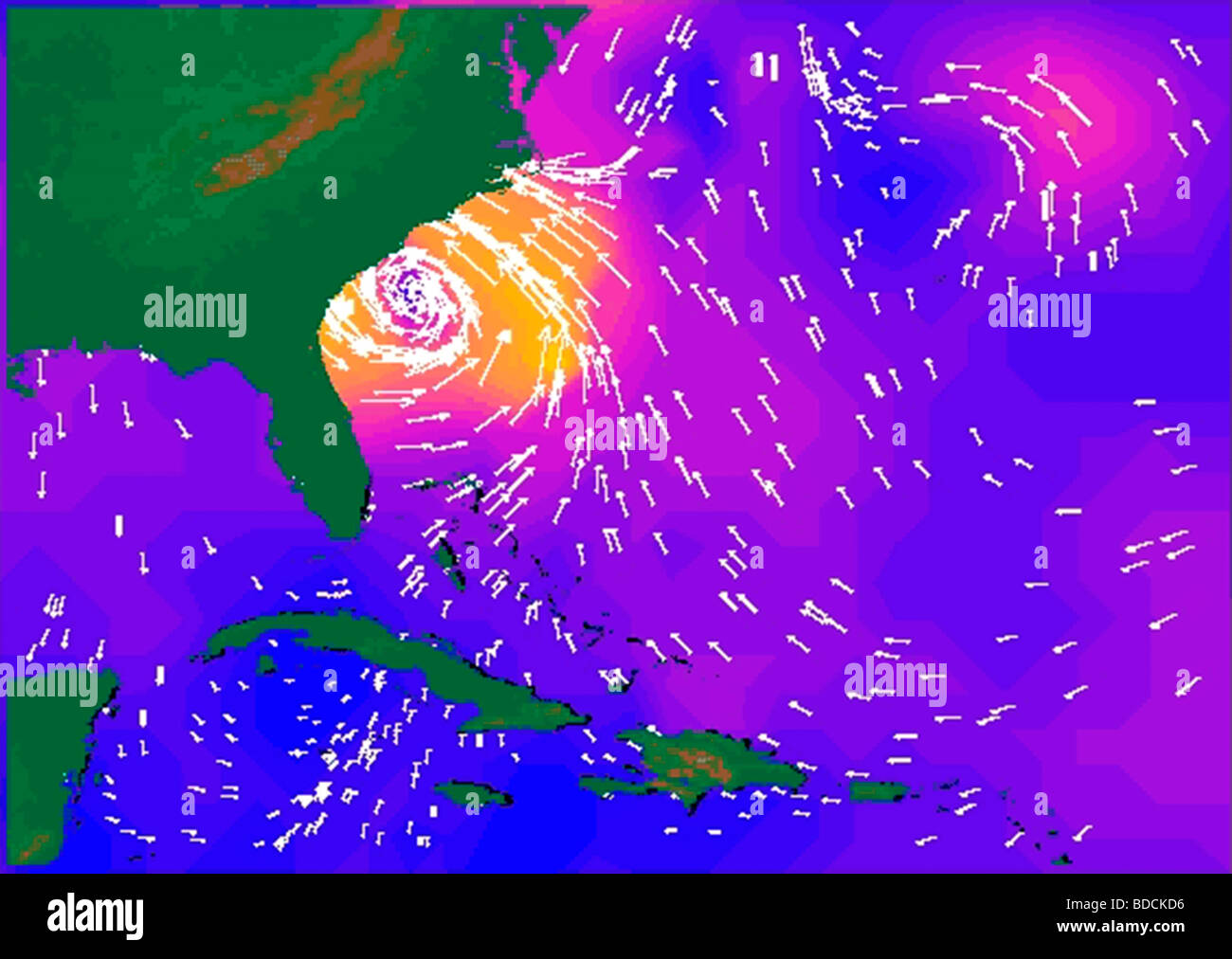

We use a "synthetic" version of weather radar for the Atlantic Ocean. It’s a cocktail of satellite imagery, dropsondes dropped from planes, and a very cool technology called High-Frequency (HF) Radar. HF radar doesn't look for rain; it looks at the waves. By bouncing signals off the salty water, scientists can map surface currents and get a proxy for what the wind is doing. It’s clever, but it’s not the same as seeing the eye of a hurricane in high resolution.

Satellites are the Real MVPs Here

Since we can't easily put a dish in the middle of the ocean, we put them 22,000 miles in the air. The GOES-R series (specifically GOES-East for the Atlantic) is basically our eyes. But there’s a catch. Most satellite data is "passive." It just looks at the light or heat coming off the clouds. It doesn't "punch" through the storm to see the rain structure like a ground-based weather radar for the Atlantic Ocean would.

That changed with the GPM (Global Precipitation Measurement) mission. This is a joint project between NASA and JAXA (the Japanese space agency). It carries the first Spaceborne Dual-Frequency Precipitation Radar. Think of it as a flying MRI machine. It scans the Atlantic in slices, giving us a 3D view of a storm's internal structure.

Why the "Cone of Uncertainty" Is So Hard to Shrink

- Data Latency: Satellite data has to be processed. It’s not "live" like the radar in your city.

- Resolution: A ground radar can see a tornado-scale rotation. A satellite often sees a 5-mile-wide pixel.

- The Bottom-Up Problem: Most weather happens in the lowest 2 kilometers of the atmosphere. Satellites struggle to see through the "clutter" near the ocean surface.

- The Power Issue: It takes a massive amount of electricity to send a radar pulse and listen for the echo. Batteries and solar panels on satellites have limits.

The National Hurricane Center (NHC) uses these satellite passes to feed their models, but they always want more. If a storm is far out, they’re basically making an educated guess based on water temperature and atmospheric pressure. It’s only when the storm gets within about 200 miles of the coast that the land-based weather radar for the Atlantic Ocean finally "sees" it and the forecast gets scary-accurate.

The Brave Pilots Flying Into the Void

When satellites aren't enough, we send the Hurricane Hunters. This is arguably the most "analog" part of modern technology. The NOAA WP-3D Orion aircraft are literally flying radar stations. They carry a Tail Doppler Radar (TDR).

👉 See also: Spectrum Jacksonville North Carolina: What You’re Actually Getting

As the pilot flies through the eyewall—which is a wild ride, by the way—the TDR scans the storm vertically. This is the highest-quality weather radar for the Atlantic Ocean data we possess. It allows forecasters to see if the storm is "tilting." A tilted storm is weak. A perfectly vertical storm is a monster. Without these planes, our intensity forecasts would be about 20% less accurate. That 20% is the difference between an "it's just a bit of rain" forecast and a mandatory evacuation order.

What’s Changing in 2026?

We’re moving away from big, expensive hardware toward "distributed" sensing. Basically, instead of one big radar, we’re using a thousand tiny ones. Companies like Saildrone are deploying autonomous boats that sit in the path of hurricanes. They don't carry radar, but they provide the "ground truth" that helps us calibrate the radar we do have.

There is also a push for "CubeSats." These are tiny, shoe-box-sized satellites. The idea is to launch a "train" of them over the Atlantic. If you have 20 CubeSats following each other, you get a fresh radar update every 15 minutes instead of waiting hours for a big satellite to orbit back around. This is the future of weather radar for the Atlantic Ocean. It’s cheaper, faster, and much harder to break in a storm.

Common Myths About Ocean Radar

People often think ships provide radar data. They don't. While most cargo ships have navigation radar, it’s designed to see other ships and icebergs, not rain. Plus, ship captains are smart. If there’s a massive storm in the Atlantic, they aren't going anywhere near it. They turn their radars off and run the other way, leaving a giant data hole right where we need it most.

Another one is that "the military has better stuff." While the Navy has incredible radar on their destroyers (the SPY-1 and SPY-6 systems), it’s optimized for picking up a missile moving at Mach 3, not a raindrop. The physics of "seeing" weather requires different wavelengths (usually S-band or C-band) than tracking aircraft.

✨ Don't miss: Dokumen pub: What Most People Get Wrong About This Site

How to Actually Use This Info

If you’re a sailor, a coastal resident, or just a weather nerd, you shouldn't just look at a standard radar map when looking at the Atlantic. You’ll see a lot of "false echoes" or just empty space.

Instead, look for "Morphed Integrated Microwave Imagery" (MIMIC). It’s a mouthful, but it’s a tool used by the Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies. It fills in the gaps between satellite passes to show you a continuous loop of how a storm is actually rotating. It’s the closest thing we have to a live, pan-Atlantic radar.

Your Actionable Checklist for Tracking Atlantic Weather:

- Stop trusting "Future Radar" loops for the deep ocean; they are purely mathematical guesses, not actual observations.

- Use the NHC’s "Aircraft Reconnaissance" page. If there’s a plane in the air, you’re getting the only real radar data available for that sector.

- Watch the "Vapor" channels on satellite feeds. Since radar is sparse, water vapor imagery shows you the "rivers of air" that steer the storms.

- Check the "Ocean Prediction Center" (OPC). They provide specialized maps that combine what little radar we have with buoy data to show wave heights.

- Look for the "Radar Estimated Rainfall" tools on sites like Tropical Tidbits. They use satellite-to-radar conversion algorithms that are surprisingly accurate for the deep Atlantic.

Understanding the limitations of weather radar for the Atlantic Ocean makes you a better observer. You realize that the "smoothness" of the maps on your evening news is a bit of an illusion. The reality is a gritty, complex, and heroic effort to piece together a puzzle using space-age sensors and 1950s-style grit. Next time you see a storm brewing off the coast of Africa, remember: there's no single eye in the sky. There’s a whole network of tech trying to make sense of the chaos.

Monitor the National Hurricane Center's "Satellite Acts" section specifically during the peak months of August and September. This is where the highest-resolution experimental radar-derived products are usually posted before they make it to mainstream apps. If you see "Deep Convection" appearing on the IR satellite imagery but the radar doesn't show much yet, trust the satellite—the radar just hasn't caught up to the curve of the Earth yet.