You’re standing on Elkhorn Avenue. The sky looks like a bruised plum, all deep purples and heavy, low-hanging greys. You pull out your phone, check the weather radar Estes Park CO results, and it shows... nothing. Just a clear green sweep of "all clear" while a raindrop the size of a nickel smacks your screen.

It happens constantly.

Living in or visiting the Gateway to the Rockies means accepting a hard truth: the colorful blobs on your phone screen are often lying to you. Or, more accurately, they aren't seeing what’s right in front of your face. Mountains do weird things to radio waves. If you’re banking your hike up to Sky Pond on a standard radar loop, you’re basically gambling with a very cold, very wet deck of cards.

The "Beam Blockage" Problem Near Longs Peak

Most people think radar is like a giant camera in the sky. It isn't. It’s a flashlight beam made of radio pulses. The nearest high-resolution NEXRAD station is KFTG, located out at Denver International Airport. Think about the geography there. To see what's happening in Estes Park, that beam has to travel over 50 miles and try to "peek" over the top of the Front Range foothills.

Radio waves travel in straight lines. The Earth is curved.

By the time the signal from Denver reaches the 8,000-foot elevation of Estes Park, the beam is actually thousands of feet above the ground. It’s literally shooting over the storm. This is why you’ll often see "clear skies" on your app while a localized microburst is currently trying to blow your patio furniture into Lake Estes. The radar is seeing the top of the clouds, or nothing at all, missing the rain falling out of the bottom.

💡 You might also like: The Lost City of Z: Why Percy Fawcett Was Right (and Wrong) About the Amazon

Then there is the physical barrier. Mountains like Lumpy Ridge and the massive shoulder of Longs Peak create "beam blockage." The radar hits the rock, bounces back, and tells the computer there’s a solid object there. Sophisticated algorithms try to filter this "ground clutter" out, but in doing so, they often delete the actual weather data right behind the mountain.

Reading Between the Pixels: The Best Tools for the Village

If the standard apps fail, what do the locals use? You have to get a bit more granular.

The NWS Boulder "Radar Gone Wild" Fix

The National Weather Service (NWS) office in Boulder is the gold standard, but even they acknowledge the "mountain gap." They use supplemental data. When looking at weather radar Estes Park CO feeds, look for "Base Reflectivity" versus "Composite Reflectivity."

- Base Reflectivity: This is the lowest angle. In the mountains, it's often blocked by terrain, but it’s the most accurate for seeing what is actually hitting the ground.

- Composite Reflectivity: This stitches together all altitudes. If this shows a dark red blob over Estes but the Base Reflectivity is clear, it means the storm is "elevated"—it’s happening high up and might not have started dumping on the ground yet. Or, it’s evaporating before it hits (virga).

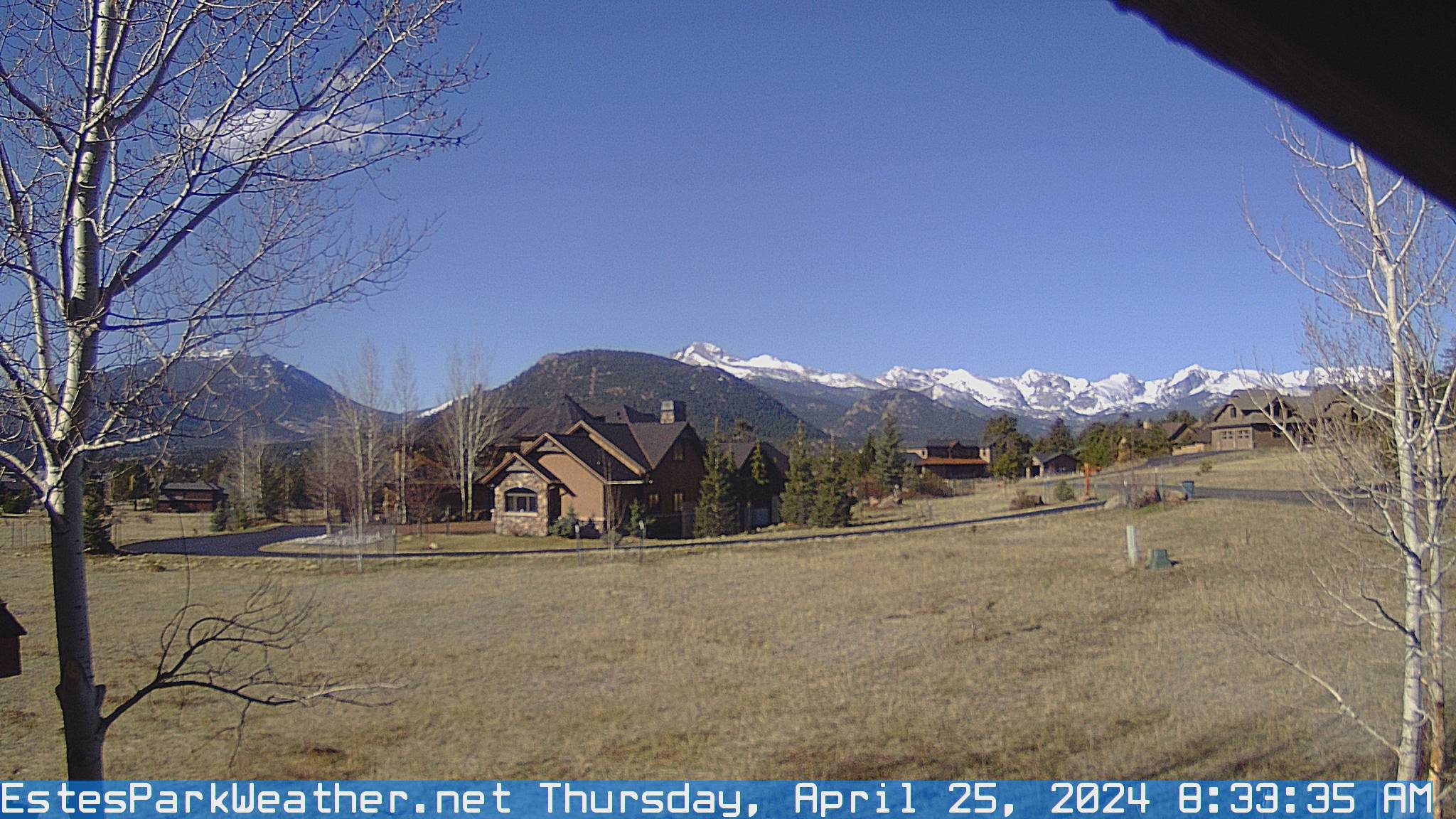

The Power of Webcams

Honestly? Sometimes the best "radar" is a visual check. The Estes Park CVB and various local businesses maintain a network of high-definition webcams. If you see the Stanley Hotel disappearing into a white mist on the Longs Peak View cam, it doesn't matter what the radar says. The snow is here.

Atmospheric Modeling (HRRR)

The High-Resolution Rapid Refresh (HRRR) model is a godsend for mountain weather. It updates every hour. Unlike the radar, which tells you what was happening five minutes ago, the HRRR uses physics to predict what will happen in the next few. For a town tucked into a bowl like Estes, these short-term models handle the "upslope" flow—where air hits the mountains and is forced upward, condensing into sudden rain—much better than a beam from Denver ever could.

Why Summer Afternoons are a Radar Nightmare

July in Estes Park follows a script. Morning is blue and perfect. By 1:00 PM, the clouds start to gather over the Continental Divide. By 3:00 PM, it’s chaos.

These are convective storms. They are small, violent, and incredibly fast. A cell can form, dump an inch of hail, and dissipate in the time it takes for a radar sweep to update twice. Because Estes Park is situated at the base of these peaks, we are in the "birth zone" for these storms.

You’ve probably noticed that the "rain" on the radar often looks like it’s moving backward or popping out of nowhere. That’s because it is. The terrain creates its own microclimates. The "weather radar Estes Park CO" search might show a storm moving toward Loveland, but a secondary "gust front" could push a new cell right back over the downtown area.

Winter and the "Dry" Radar Myth

Winter is even trickier. Snowflakes are less "reflective" than raindrops. To a radar beam, a heavy, dry snowstorm in the Rockies can look like a light drizzle. This is why "Surprise Totals" are so common in Larimer County.

If the air is cold enough, the moisture is squeezed out of the atmosphere very efficiently. You might see "light green" on the map—usually indicative of a sprinkle—but because the "snow-to-liquid ratio" in Estes Park can be 20:1, that "sprinkle" ends up being six inches of powder by morning.

Real-World Advice for Navigating the "Estes Gap"

Don't just stare at the moving map. It's a trap.

- Check the Pressure: If your watch or phone has a barometer, watch it. If the pressure drops suddenly, the radar is irrelevant. A storm is coming.

- Look West: In Estes, weather almost always tracks from the West/Northwest over the Divide. If the clouds over Trail Ridge Road are turning that specific shade of "mean charcoal," get off the trail.

- Use the Terminal Pulse Doppler (TDWR): If you can find a weather app that lets you select the source, try to find the TDEN (Denver) radar. It’s a higher-frequency radar used for the airport. While it has shorter range, it sometimes picks up low-level moisture that the big NEXRAD towers miss.

- Trust the Wind: An "upslope" wind (blowing from the East/Northeast) is the most dangerous setup for Estes Park. It pushes moisture against the mountains, where it has nowhere to go but up. This leads to the most intense, prolonged precipitation events in the region’s history, including the 2013 floods and the 1976 Big Thompson event.

The mountains are big. The radar is far away.

👉 See also: Finding Your Way: What the Mt Rainier Trail Map Won't Tell You Until You're There

Nature doesn't care about your 5G connection or the "10% chance of rain" on your home screen. In Estes Park, the geography dictates the weather, and the geography is much more powerful than the technology we use to track it.

Next Steps for Staying Safe:

- Bookmark the NWS Boulder "Area Forecast Discussion": This is where actual meteorologists write in plain English about why they do or don't trust the radar models for the day. It’s the "secret sauce" for locals.

- Download an app with "Tilt" control: RadarScope or similar pro-sumer apps allow you to change the angle of the radar beam. For Estes Park, looking at the lowest tilt (0.5 degrees) is essential, even with the blockage.

- Set up "Custom Alerts" for Larimer County: Don't rely on the app's visual map; set up text alerts for National Weather Service warnings, which are issued based on ground reports (spotters) rather than just radar data.