Buffalo is different. If you live here, you know the vibe when the sky turns that weird, bruised shade of purple-grey in late November. You aren’t just looking at the clouds; you’re looking at your phone, specifically at the weather doppler Buffalo NY feeds that basically dictate whether you’re going to work or spending the next six hours digging a tunnel to your mailbox.

It’s intense.

Most people think radar is just a map with some green and red blobs. In Western New York, it’s a survival tool. Because of our unique geography—sandwiched between Lake Erie and Lake Ontario—the technology behind our local doppler systems has to work twice as hard as it does in, say, Kansas. Out there, storms are big and predictable. Here? We deal with "lake effect" bands that can be three miles wide, dump four feet of snow on Orchard Park, and leave downtown Buffalo under a perfectly sunny sky. That kind of precision requires a massive amount of technical heavy lifting.

How the KBUF Radar Actually Sees Through the Chaos

The heart of the system is the WSR-88D, specifically the one located in Cheektowaga. Its call sign is KBUF. If you’ve ever looked at a local news app and seen the "live" radar, you’re likely looking at data processed from this specific station, which is maintained by the National Weather Service (NWS) Buffalo office.

But here is where it gets tricky. Radar works by sending out a pulse of energy. That energy hits something—a raindrop, a snowflake, a bug, or even a wind turbine—and bounces back. The time it takes to return tells the computer how far away the object is. The "Doppler" part of the name refers to the change in frequency of that returning signal. If the frequency shifts higher, the wind is moving toward the radar. If it drops, it's moving away.

This is crucial for spotting rotation in thunderstorms, which helps issue tornado warnings. But in Buffalo, we care more about "Dual-Pol" or Dual-Polarization.

Up until about 2013, radars only sent out horizontal pulses. They could tell how wide a raindrop was, but not how tall. Dual-Pol sends out both horizontal and vertical pulses. Why does that matter for a weather doppler Buffalo NY search? Because it allows meteorologists to tell the difference between a big, wet snowflake, a pellet of sleet, and a raindrop. When the "rain-snow line" is hovering right over the I-190, that technical distinction is the difference between a rainy commute and a 20-car pileup.

The lake complicates everything, though.

Lake effect snow is often "shallow." It happens low in the atmosphere. Because the Earth is curved, the radar beam gets higher and higher above the ground the further away it travels. By the time the beam from Cheektowaga reaches the southern Tier or way up toward Watertown, it might be shooting right over the top of the snow clouds. This is why you’ll sometimes see a clear radar screen while you’re standing in a whiteout. It's not that the radar is "broken"—it's just literally looking over the storm's head.

💡 You might also like: Why Memory Foam Earphone Tips Make or Break Your Listening Experience

The Local News Arms Race: High-Frequency vs. National Feeds

You’ve probably noticed that WGRZ, WIVB, and WKBW all claim to have the "most powerful" or "most accurate" radar. It’s a bit of a marketing game, but there’s real tech behind it.

The National Weather Service radar (KBUF) is the gold standard for long-range detection. It has a massive dish and huge power. However, it takes time to complete a full 360-degree scan at multiple heights. In a fast-moving lake effect situation, five or six minutes between scans feels like an eternity.

Local stations often supplement this with their own "X-Band" or "C-Band" radar units. These are smaller and have a shorter range, but they spin faster. They provide "high-resolution" updates. Think of it like the difference between a high-quality professional photograph that takes a minute to develop versus a grainy but instant livestream. To get the full picture of weather doppler Buffalo NY, experts actually look at a mosaic of both.

Then there’s the "noise."

Buffalo has a lot of wind farms, especially as you move south toward Wyoming County. Those massive spinning blades reflect radar energy just like a storm does. It creates "ground clutter." For years, this was a huge headache, but modern algorithms are getting better at filtering out the "fake" storms caused by green energy. Honestly, it's pretty impressive that a computer can distinguish between a turbine blade and a wall of Lake Erie moisture, but that's the level of sophistication we're dealing with now.

Why Your App Might Be Lying to You

Here is a hard truth: that default weather app on your iPhone or Android is probably the worst way to track a Buffalo storm.

Most of those apps use "smoothed" data. They take the raw, pixelated radar blocks and use an algorithm to make them look like soft, flowing colors. It looks pretty, but it’s inaccurate. It hides the "fine line" boundaries where the weather actually changes.

🔗 Read more: Archive of Deleted Tweets: How to Find What’s Been Erased

If you really want to know what's happening, you need to look at the "Base Reflectivity" and "Correlation Coefficient" products. Base Reflectivity is the standard "how much stuff is in the air" view. Correlation Coefficient (CC) is the "how similar is the stuff" view. In a major Buffalo storm, if the CC value drops, it often means the radar is picking up "debris"—meaning a tornado has touched down or the wind is so strong it's lofting non-weather objects into the sky.

In winter, CC helps identify the "melting layer." If you see a weird ring of different colors around the radar site, that’s often where snow is turning to rain as it falls. Knowing exactly where that ring is located tells you where the ice is going to build up on the power lines.

The Impact of Geography on Radar Reliability

The Niagara Escarpment and the hills of the Southern Tier create "radar shadows."

If you’re down in a valley in Ellicottville, the radar beam might be blocked by a ridge. This is why the NWS often coordinates with "spotters"—real humans with snow rulers—to verify what the weather doppler Buffalo NY is seeing. It's a hybrid system. We have millions of dollars in silicon and steel in the air, but we still need a guy named Dave in Hamburg to tweet a picture of his yard to confirm the radar isn't missing a localized burst.

Interestingly, the "fetch" of the wind over Lake Erie is the primary driver of the radar's workload. If the wind blows along the long axis of the lake (southwest to northeast), it picks up maximum moisture. This creates those long, skinny "screamer" bands. On a radar map, these look like a finger pointing directly at South Buffalo or Cheektowaga. If that band shifts just two degrees to the north, the airport closes. If it shifts two degrees south, the airport is bone dry while the Bills stadium gets buried.

📖 Related: Why the TCL 85 Inch Roku TV is the Smartest Way to Get a Massive Screen Without Going Broke

This is why the "velocity" view on the doppler is so vital. It’s not just about where the snow is now; it’s about the wind vectors pushing that band. If the velocity shows a slight shift in wind direction over the lake, you can predict exactly when the snow will move from the Northtowns to the Southtowns.

Real-World Use: How to Read the Map Like a Pro

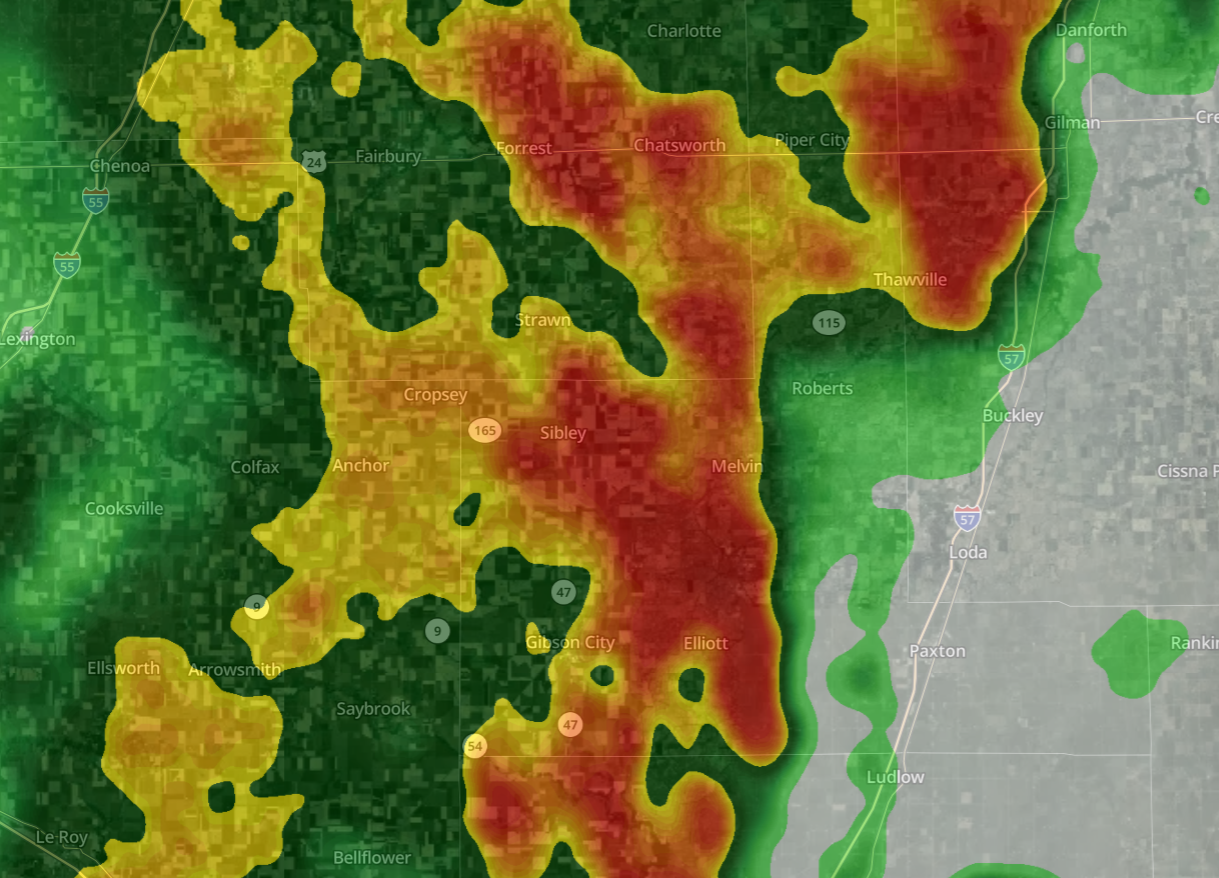

When you open a radar map for Buffalo, don't just look for colors. Look for the "gradient."

A "tight gradient" is when the color changes from nothing to dark red in a very short distance. That indicates a wall of snow. If you are driving toward that, expect visibility to drop to zero in seconds. If the colors are "fuzzy" or spread out, it’s likely just light flurries or scattered showers.

Also, check the "Loop." A single snapshot of weather doppler Buffalo NY tells you nothing about the trend. Is the band intensifying? Is it breaking apart? Lake effect bands usually "pulsate." They get bright, then dim, then bright again. This usually corresponds with "fetch" cycles and moisture availability from the lake surface.

Actionable Steps for Western New Yorkers

Stop relying on the "sunny/cloudy" icons on your phone. They are almost useless in a lake-effect environment. Instead, do this:

- Download a Raw Data App: Use something like RadarScope or the official NWS mobile site. These don't "smooth" the data. You see exactly what the KBUF dish sees.

- Learn the "Tilt": If your app allows it, look at "Tilt 1" (the lowest angle) and "Tilt 4" (a higher angle). If there’s a lot of action on Tilt 4 but nothing on Tilt 1, the snow is evaporating before it hits the ground. This is called "virga."

- Watch the Velocity: In the summer, look for "couplets"—green and red colors right next to each other. That’s rotation. That’s when you head to the basement. In the winter, watch for the wind direction over the lake to see if the snow band is about to "drift" into your neighborhood.

- Trust the CC: If it’s winter and the Correlation Coefficient is messy, it’s probably a "mixed bag" of sleet and freezing rain. Wear the good boots and give yourself an extra 20 minutes for the commute.

- Ignore the "Precipitation Type" Toggles: Many apps try to guess if it's rain or snow based on temperature. They are often wrong because they don't account for "warm air aloft." Trust your eyes and the raw reflectivity more than the app's color-coded "snow" layer.

Buffalo weather is a beast, but the technology we have to track it is some of the most advanced in the world. We have to have it. Without the constant, 24/7 scanning of the weather doppler Buffalo NY systems, the city would grind to a halt every time Lake Erie decided to get angry. Understanding how to read that data isn't just for weather nerds anymore; it's a basic life skill for anyone living in the 716.

Check the loops, watch the wind vectors, and always keep a shovel in the trunk, even if the radar looks clear for the next ten minutes. Things change fast here.