He sat on a lonely train platform in Tutwiler, Mississippi, back in 1903. Just a man waiting for a delayed ride. Then, the sound started. A lean, ragged Black man pressed a knife blade against the strings of a guitar, sliding it to create a haunting, moaning wail. He sang about "goin' where the Southern cross the Dog." William Christopher Handy, a classically trained musician with a sharp ear for business, didn't just hear a song; he heard a revolution.

That moment changed everything.

Handy wasn't the first person to play the blues. He didn't invent the 12-bar structure or the "blue note." But without WC Handy father of the blues, that raw, Delta sound might have stayed a local secret, buried in the dusty fields of the Jim Crow South. He took a folk tradition and turned it into a global industry. He codified the music. He wrote it down. He made it something you could buy, sell, and whistle on a street corner in New York City.

The Tutwiler Revelation and the Birth of a Genre

Before that night in Tutwiler, Handy thought the music of the poor, rural South was "weird." He was a son of preachers. His father thought musical instruments were "tools of the devil." But Handy had a different vision. He was a bandleader who knew how to read the room—and the charts. When he saw people throwing money at a trio of local musicians playing "over and over" a repetitive, three-line strain, he realized he was looking at a goldmine.

It wasn't just art. It was economics.

He moved to Memphis. He started soaking up the sounds of Beale Street. In 1909, he wrote a campaign song for a local politician named Edward "Boss" Crump. That song, originally "Mr. Crump," eventually became "The Memphis Blues." It was the spark. While some folks argue about who really played the first blues note, nobody disputes that Handy was the one who figured out how to translate that feeling onto sheet music.

Why the "Father" Title is Actually Complicated

Some purists get annoyed by the title "Father of the Blues." They'll tell you that the blues existed long before Handy put pen to paper. And they're right. It was a grassroots, oral tradition born from work songs, spirituals, and field hollers.

💡 You might also like: Is Steven Weber Leaving Chicago Med? What Really Happened With Dean Archer

But here’s the thing: Handy never claimed he birthed the genre from his own rib. He called himself the "father" because he was the architect. He built the house where the music lived. Before him, the blues was fluid and disorganized. He standardized the 12-bar form. He introduced the "flatted" third and seventh notes—the "blue notes"—to a wider audience that had never heard such "dissonant" beauty.

He was a bridge. He connected the rural South to the urban North.

Think about the sheer grit it took to do this in the early 1900s. A Black man in America, navigating the predatory world of music publishing, starting his own company because white publishers were ripping off Black artists. Handy wasn't just a songwriter; he was a pioneer of Black entrepreneurship.

The St. Louis Blues: A Masterpiece of Melancholy

If you want to understand the genius of WC Handy father of the blues, you have to look at "The St. Louis Blues." Published in 1914, it is arguably the most famous blues song ever written. It combines a habanera rhythm with a standard blues structure. It's sophisticated. It’s catchy. It’s heartbreaking.

"I hate to see that evening sun go down."

That opening line captures a universal human ache. Handy wrote it after seeing a woman on the streets of St. Louis, mourning her "man's" departure. He took her real-world pain and turned it into high art. By the 1920s, the song was a massive hit. Bessie Smith’s 1925 recording, featuring a young Louis Armstrong on cornet, is basically the "Citizen Kane" of blues records. It’s perfect.

📖 Related: Is Heroes and Villains Legit? What You Need to Know Before Buying

The Business of the Blues and the Pace & Handy Agency

Handy didn't want to be a starving artist. He wanted a seat at the table. He partnered with Harry Pace to form the Pace & Handy Music Company. They moved to New York’s Gaiety Theatre building, right in the heart of the "Black 50th Street."

This wasn't just about printing sheet music. It was a statement of independence.

He faced constant hurdles. Piracy was rampant. Copyright laws were often ignored when it came to Black creators. Yet, Handy persisted. He proved that Black music was commercially viable on a massive scale. He paved the way for the Harlem Renaissance and the eventual explosion of jazz. Honestly, without Handy’s business savvy, the "Jazz Age" might have sounded very different.

Myths and Misunderstandings: Setting the Record Straight

People often think Handy was just a songwriter. Actually, he was an incredibly accomplished cornetist and bandleader. He toured the country with his orchestra, bringing the blues to places that had only ever heard marches or light classical music.

Another big misconception? That he "sanitized" the blues for white audiences.

Sure, he made it palatable for the mainstream, but he didn't strip it of its soul. He was a folklorist. He spent years documenting the variations of the music he heard in the Delta. He was worried that if someone didn't write it down, this unique American voice would vanish. He was a preservationist with a paycheck.

👉 See also: Jack Blocker American Idol Journey: What Most People Get Wrong

He was also almost entirely blind for a significant portion of his later life. Despite this, he continued to compose and lead his business. That kind of resilience is what the blues is actually about. It's not just about being sad; it's about surviving the sadness.

The Lasting Impact on Modern Music

Every time you hear a rock riff or a soul ballad, you’re hearing the echoes of WC Handy. The 12-bar structure he popularized is the literal DNA of Rock 'n' Roll. Chuck Berry, Elvis Presley, The Rolling Stones—they all owe a royalty check to the man who sat on that platform in Tutwiler.

Handy died in 1958. Over 25,000 people attended his funeral in Harlem. The streets were packed. People knew then, as we know now, that he was the giant upon whose shoulders everyone else stood.

The Handy Legacy Beyond the Notes

The legacy of WC Handy father of the blues isn't just in the Library of Congress. It’s in the way we think about American identity. He took the "low" culture of the marginalized and proved it was the "high" culture of the nation.

He didn't just give us songs; he gave us a vocabulary for our feelings.

When you look at his autobiography, Father of the Blues, he doesn't sound like a man boasting about his own greatness. He sounds like a man who was lucky enough to be in the right place at the right time with the right set of ears. He saw the value in people who were being told they were valueless.

Actionable Steps for Exploring the Legacy of WC Handy

If you really want to understand the impact of WC Handy, don't just read about him. You need to experience the geography and the sound.

- Visit the W.C. Handy Birthplace, Museum & Library: Located in Florence, Alabama, this is a humble log cabin that houses his piano and several original scores. It’s a stark reminder of how far he traveled from his roots.

- Listen to the "Big Three": Start with the original sheet music versions or early recordings of "The Memphis Blues," "The St. Louis Blues," and "Beale Street Blues."

- Compare the Covers: Listen to Bessie Smith’s version of "St. Louis Blues," then jump to Louis Armstrong’s version, and then maybe a modern jazz interpretation. Notice how the structure Handy codified allows for endless improvisation.

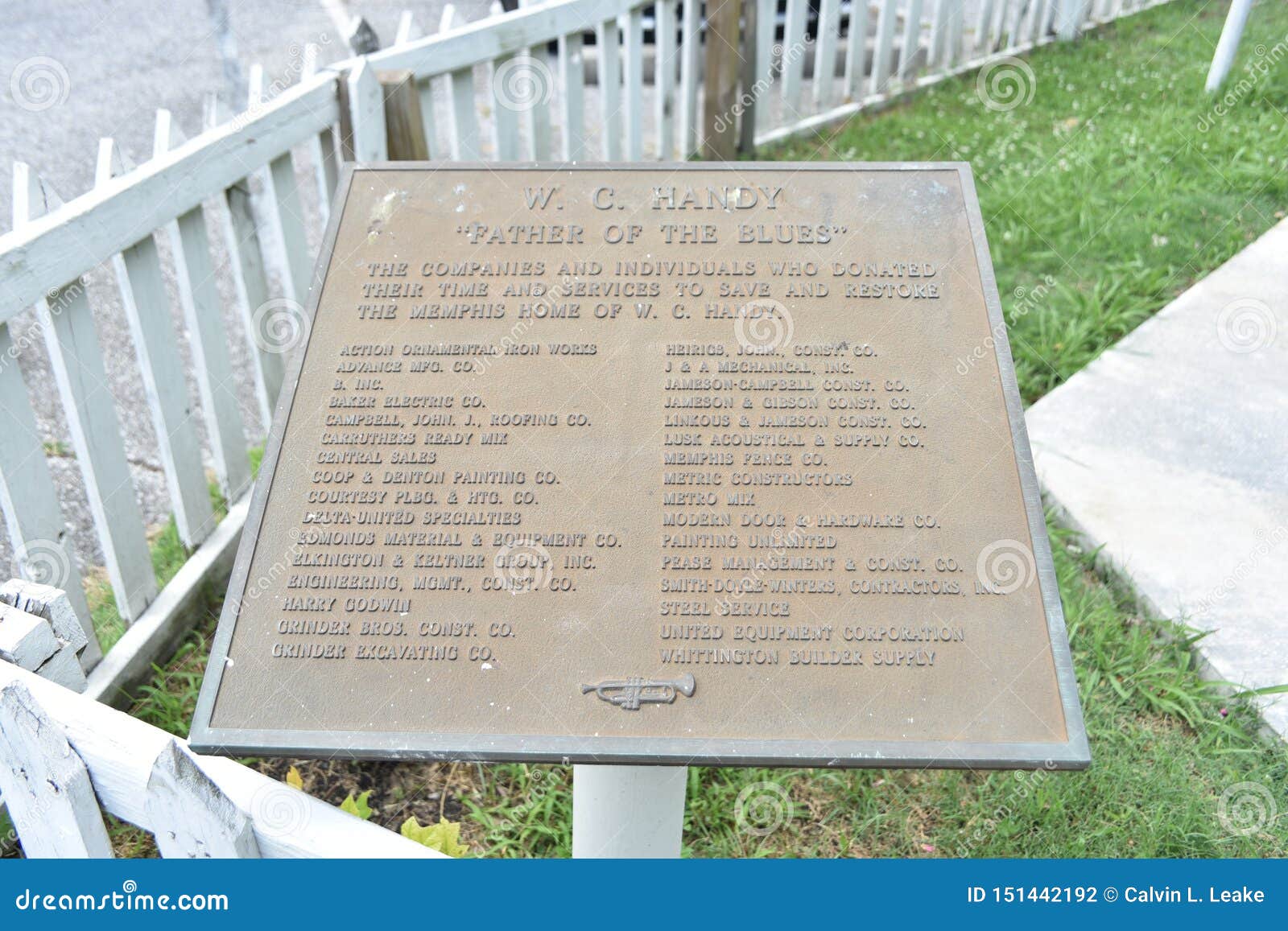

- Walk Beale Street: While it’s very touristy now, the W.C. Handy Park in Memphis still holds the spirit of the music. Stand near his statue and imagine the sound of a brass band cutting through the humidity of 1910.

- Read his Autobiography: Pick up a copy of Father of the Blues. It’s a fascinating look at the post-Reconstruction South and the struggle of a Black artist trying to make it in a world stacked against him.

The blues is a living thing. It’s a conversation between the past and the present. Every time a kid picks up a guitar and plays those three basic chords, the "Father of the Blues" is right there in the room, nodding his head to the beat.