You’ve probably seen some woodcarvings in your life. Maybe a little bird from a craft fair or some ornate furniture in an old house. But what happens when a person spends 75 years—basically their entire conscious existence—obsessing over the physics of a steam engine and the grain of a piece of ebony? You get the Warther Museum & Gardens in Dover, Ohio. It’s a place that feels less like a traditional museum and more like a fever dream of mechanical precision. Honestly, calling Ernest "Mooney" Warther a "woodcarver" is kind of like calling Nikola Tesla an "electrician." It doesn't quite cover the scope of the madness, or the genius.

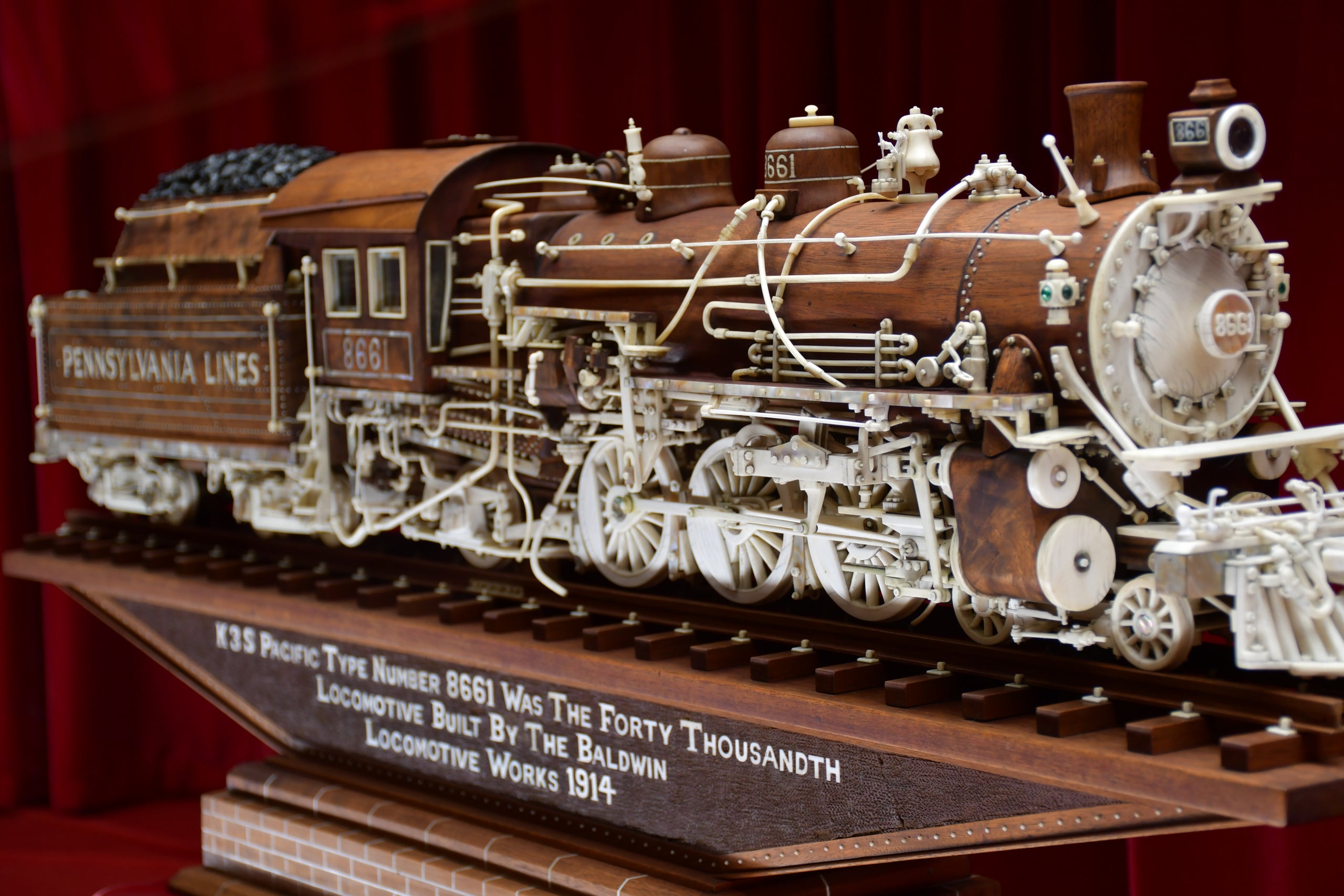

Most people stumble upon this spot while driving through Ohio's Amish Country, expecting a quaint little stop with some whittled toys. What they find instead is a collection of 64 ivory and ebony steam engines that are so detailed they actually function. Well, they would function if you could shrink a conductor down to the size of a thimble. Mooney didn't just carve the shells; he carved the pistons, the valves, and the piping to scale.

The Man Who Couldn't Stop Carving

Ernest Warther was born in 1885. He was a son of Swiss immigrants, and he started carving because he found a pocketknife in the dirt while herding cows. That’s it. That’s the origin story. There was no formal training, no apprenticeship under a master sculptor. He was just a kid with a sharp blade and a brain that seemed to understand mechanical engineering intuitively. He spent his days working in a steel mill—the American Sheet and Tin Plate Company—and his nights in a tiny workshop behind his house.

He worked in that mill for 23 years. Think about that. He did grueling, repetitive labor all day, then came home to do incredibly minute, stressful detail work all night. He eventually quit the mill because the New York Central Railroad offered him a deal: they’d pay him to travel around and show off his carvings as an advertisement for the power of steam. But Mooney hated being away from his family and his workshop. He turned down a literal fortune to stay in Dover. He just wanted to carve.

The sheer volume of work is staggering. We aren't talking about a few dozen pieces. We're talking about a lifetime of output that includes a working model of the steel mill where he worked, complete with tiny men and moving parts. It’s all carved from wood, bone, and ivory. He used a knife he designed himself—a short, stubby blade that allowed for immense leverage. You can still buy versions of that knife at the museum today. They're still made by the family.

Why the Plier Tree is a Geometric Nightmare

If you walk into the Warther Museum & Gardens and don't spend at least ten minutes staring at the Plier Tree, you've missed the point of the whole trip. In 1913, Mooney decided to show off. He took a single block of wood and made 31,000 cuts. He didn't glue anything. He didn't use a lathe. He just cut.

When he was finished, that one block of wood opened up into a branching structure of 511 interconnected, working pliers. If you fold them back down, they go right back into that original block of wood. It’s a mathematical impossibility made real. He did it to prove that he had mastered the "living hinge."

He used to perform this for crowds. He’d take a small piece of wood and, in about 30 seconds, make ten cuts that resulted in a fully functional pair of pliers. It’s a parlor trick, sure, but it’s a parlor trick that requires a terrifyingly deep understanding of wood grain and spatial geometry. He did it over 750,000 times in his life. He gave them away to kids. Imagine being a kid in the 1930s and getting a hand-carved mechanical toy from a guy who basically looked like a wizard in a workshop.

More Than Just Engines: The Gardens and the Buttons

It wasn't just Mooney. His wife, Frieda, was equally obsessed, but her medium was different. She collected buttons. Now, "collecting buttons" sounds like the most boring hobby imaginable. It sounds like something a Victorian ghost would do. But Frieda was a force of nature. She didn't just put them in jars; she mounted them in intricate, geometric patterns on the walls of a separate building on the property.

There are over 73,000 buttons on display.

👉 See also: Oneida Lake Inn Sylvan Beach: What You Should Know Before You Book

They are organized by theme, color, and material. There are buttons made of pearl, glass, metal, and even calico. It’s a massive, kaleidoscopic installation that predates "found object" art by decades. The gardens outside are an extension of this same meticulous energy. Frieda was the primary force behind the Swiss-style gardens that surround the home and workshop. Even today, the family maintains the grounds with the same level of intensity. It’s a literal sanctuary of organized beauty in the middle of a small Ohio town.

The Evolution of Steam

The main hall of the museum is a chronological journey through the history of steam power. Mooney didn't just carve random trains; he carved the history of the locomotive.

- The early experiments of Hero of Alexandria (basically a steam-powered ball).

- The "DeWitt Clinton," which looks more like a stagecoach on rails than a train.

- The massive "Big Boy" locomotives of the 1940s.

The "Big Boy" carving is the crown jewel. It’s eight feet long. It has over 5,000 parts. Every single part is carved to a tolerance of 1/64th of an inch. And remember, he’s doing this with ivory. This was back when ivory was a standard material for carving (the museum is very transparent about the age of the ivory and the ethics of it, noting that most of it was sourced decades ago before modern bans). The contrast between the dark ebony wood and the white ivory makes the mechanical details pop in a way that photos honestly can't capture. You have to see the tiny rivets. You have to see the way the bell actually swings.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Experience

People think they’re going to a "train museum." It’s not a train museum. If you go there expecting a bunch of Lionel sets buzzing around a track, you're going to be confused. This is an art museum focused on the limit of human patience.

There's also this misconception that Mooney was some kind of hermit. He wasn't. He was incredibly social. He loved people. He would sit in his workshop—which is still there, preserved exactly as it was—and talk to anyone who walked in. He’d carve pliers while telling stories. The museum keeps that vibe alive. It’s still run by the third and fourth generations of the Warther family. When you walk in, you’re often talking to a Warther. That’s rare. In an era of corporate-owned "attractions" and soulless gift shops, this place feels stubbornly personal.

The Knife Shop Legacy

Mooney realized early on that if he wanted to carve the way he did, he needed better tools. He started making his own knives using high-grade steel. Eventually, local butchers and neighbors started asking for them because they held an edge better than anything else on the market.

This turned into a legitimate business. Today, Warther Cutlery is a separate but connected entity. They still make kitchen knives using the same techniques Mooney developed. They use a "spotting" finish on the blades—that swirly, circular pattern—which was originally designed to hide scratches, but now it’s their signature. It’s a weirdly poetic side gig: the man who carved ivory engines for fun ended up creating a tool company that sustains his family over a century later.

Why This Matters in 2026

We live in a world of 3D printing and AI-generated imagery. You can tell a computer to "design a complex steam engine" and it’ll spit out a blueprint in three seconds. But there is something deeply grounding about standing in front of a piece of wood that took a human being six months of manual labor to finish.

Warther Museum & Gardens serves as a reminder of what the human hand is capable of when it's guided by a singular, unyielding focus. It’s about the "flow state" before that was a buzzword. Mooney didn't have an iPhone. He didn't have Netflix. He had a knife and a piece of wood. There is a quietness to the museum that forces you to slow down. You can't rush through it because the details won't let you. You'll catch a glimpse of a tiny, hand-carved chain link and realize it's all one piece of wood, and you'll just... stop.

Planning a Visit: The Logistics

If you're actually going to go, here’s the deal. It’s located in Dover, Ohio, about 20 minutes south of Canton (where the Pro Football Hall of Fame is).

- Timing: Give yourself at least two to three hours. The film they show at the beginning is actually worth watching—it gives context to Mooney’s life that makes the carvings more impressive.

- The Workshop: Spend time in the original workshop. Look at the ceiling. Mooney used to staple the labels of the tobacco he chewed to the ceiling rafters. It's those little human touches that make the place feel real.

- The Gardens: If it's raining, the gardens are still beautiful, but obviously, a clear day is better for seeing Frieda’s work.

- The Knife Shop: If you're a cook, bring some extra cash. The knives aren't cheap, but they are "buy it for life" quality.

The Actionable Insight: Finding Your Own "Pliers"

The real takeaway from the Warther legacy isn't that everyone should go out and start carving ivory. That's not practical. The takeaway is the value of the "secondary craft." Mooney had his day job at the mill, but his identity was in his workshop.

📖 Related: Moose Migration Sweden Live Stream: Why Millions Are Addicted to the Slowest Show on Earth

In a digital age, having a tactile, physical hobby—something that requires manual dexterity and produces a tangible result—is a massive boost for mental health. Whether it’s gardening like Frieda or woodcarving like Mooney, there is a specific kind of peace found in repetitive, skilled labor.

Next Steps for Your Visit:

- Check the Schedule: The museum is open year-round, but they do special "Christmas Tree Festival" events in November that are massive draws for locals. If you want a quiet experience, avoid those weeks.

- Look for the "Dover Train": Ask the guides about the model Mooney built of the local steel mill. It's often overshadowed by the locomotives, but the social history behind it is fascinating.

- Examine the Knife Construction: Go to the cutlery shop and ask to see how the blades are tempered. Understanding the metallurgy makes you appreciate the carvings even more because you realize the strength of the tools he was using.

- Practice Observation: Try to find a single part of a carving that seems "impossible" and trace the grain of the wood. It’s a great exercise in understanding how he worked around the natural limitations of his materials.

The Warther Museum & Gardens isn't just a collection of objects. It's a 100-year-old argument for taking your time, doing things right, and letting yourself get obsessed with the details. It’s a weird, wonderful, and deeply American place that reminds us that "handmade" used to mean something almost supernatural.