Henry Fonda was miserable. It’s the mid-1950s, and he’s stuck in Italy, sweating under heavy wool uniforms, trying to play a character half his age. Most people remember Audrey Hepburn’s luminous face when they think of the 1956 epic, but the story of war and peace henry fonda is actually a masterclass in what happens when a legendary actor is cast in a role that fits him like a cheap suit. It’s a strange, sprawling, three-and-a-half-hour beast of a movie.

Look, Tolstoy is hard. Adapting a 1,200-page Russian masterpiece into a Hollywood blockbuster was always going to be a headache. But casting Henry Fonda—the guy who defined the American everyman—as Pierre Bezukhov? That was a choice.

Pierre is supposed to be this awkward, bumbling, nearsighted, and deeply spiritual Russian aristocrat. He’s in his early twenties at the start of the book. Fonda was 50. You can see the math doesn't quite work. Yet, there’s something about his performance that keeps film historians talking decades later. It’s not that he was bad; it’s that he was so Henry Fonda in a world that needed him to be someone else.

The Massive Production That Nearly Broke Dino De Laurentiis

The 1956 version of War and Peace wasn't just a movie; it was a logistics nightmare. Dino De Laurentiis and Carlo Ponti wanted to prove that Italy could out-Hollywood Hollywood. They threw millions of dollars at it. They hired King Vidor, a veteran director who knew how to handle scale.

They also had to deal with a literal army. To film the Battle of Borodino, they didn't have CGI. They used 15,000 Italian soldiers as extras. Imagine the catering bill. Honestly, the scale of the production is probably the only thing that actually matches the weight of Tolstoy's prose.

Fonda took the role largely because he wanted to work with King Vidor and, frankly, the paycheck was massive. But he realized pretty quickly that he was physically wrong for it. Pierre Bezukhov is described by Tolstoy as a "large, stout, heavily built young man with close-cropped hair and spectacles." Fonda was lean, aging, and had that unmistakable midwestern gait.

To try and bridge the gap, Fonda wore padding. He wore glasses that actually blurred his vision, making him stumble around naturally. He tried to capture the soul of Pierre—the seeker, the man looking for meaning in a world of violence—even if he couldn't capture the age.

Why the Critics Weren't Kind to the War and Peace Henry Fonda Casting

When the film hit theaters, the reviews were... mixed. Actually, they were kind of brutal regarding Fonda. Most critics couldn't get past the fact that one of America’s most recognizable stars was pretending to be a Russian count while looking like he just stepped off the set of The Grapes of Wrath.

👉 See also: The Real Story Behind I Can Do Bad All by Myself: From Stage to Screen

It’s a bit of a tragedy, really.

Fonda is an actor of incredible interiority. He’s brilliant at showing you what a man is thinking just by the way he holds his jaw. But Pierre needs a certain kind of vulnerability that feels youthful. In the hands of a 50-year-old Fonda, Pierre’s existential wandering felt more like a mid-life crisis.

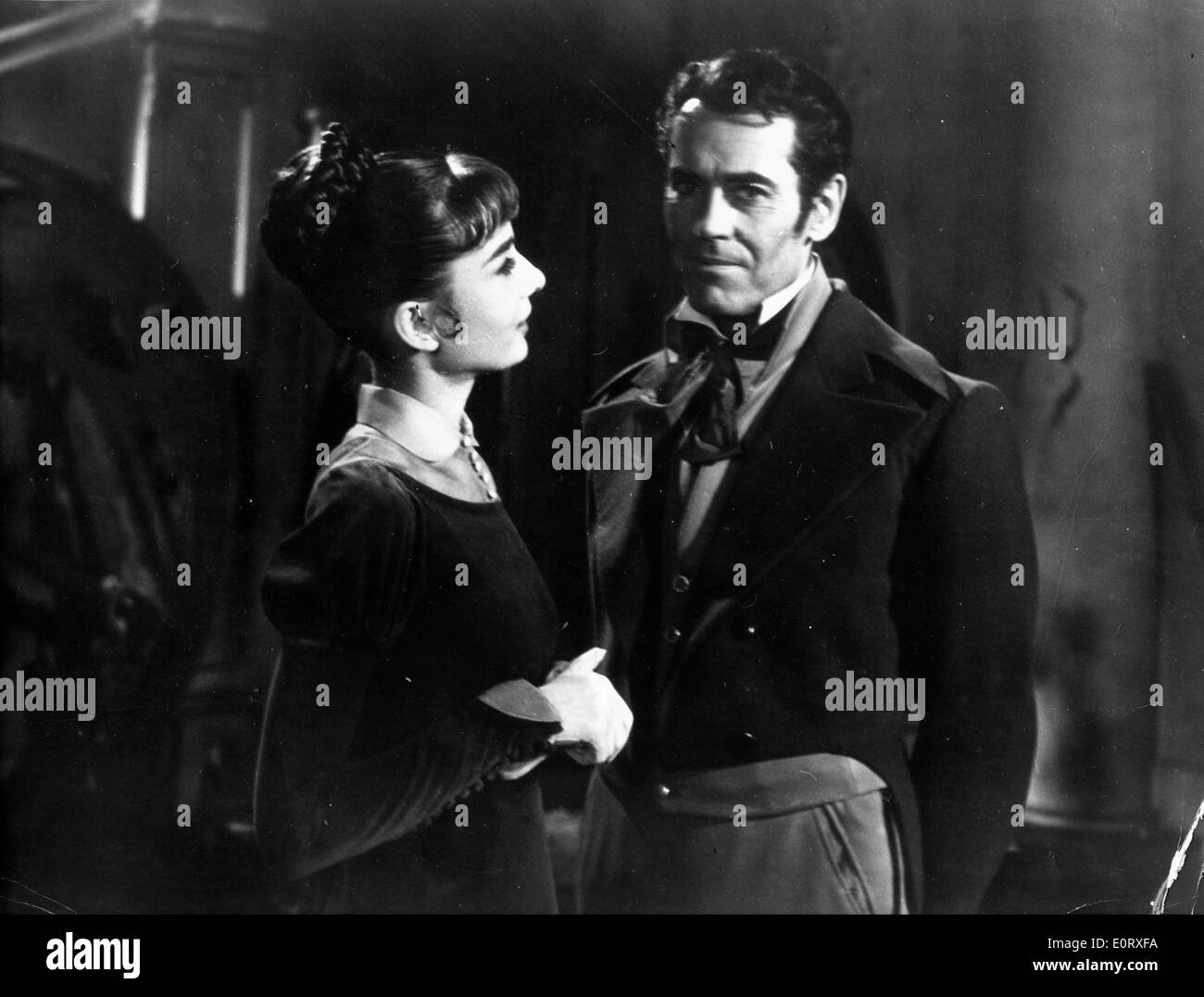

- Audrey Hepburn as Natasha Rostova: She was the saving grace. Even the harshest critics admitted she was born for the role.

- Mel Ferrer as Prince Andrei: He was fine, if a bit stiff, but the chemistry between him and Hepburn (his real-life wife at the time) was palpable.

- The Cinematography: Jack Cardiff’s work is stunning. The VistaVision frames are lush.

- The Script: Six different writers worked on it. It shows. The dialogue often feels like it's trying to summarize a cliffnotes version of the philosophy rather than letting the characters live.

People often compare this version to the 1966 Soviet adaptation by Sergei Bondarchuk. That one is seven hours long and uses real Russian landscapes. By comparison, the 1956 film feels like a "Greatest Hits" album played by a very talented cover band.

The Pierre Problem: An Actor Out of His Element

Let's be real: Pierre is the heart of the book. If you get Pierre wrong, the whole structure of the story wobbles. In the 1956 War and Peace, Henry Fonda plays Pierre as a quiet, thoughtful American intellectual who happens to be wearing a cravat.

There's a specific scene—the duel with Dolokhov—where you can see Fonda struggling. Pierre is supposed to be terrified and incompetent, a man who has never held a pistol. Fonda plays it well, but there’s a grit in his eyes that feels too much like Tom Joad. You keep expecting him to start a labor union instead of joining the Freemasons.

Interestingly, Fonda himself was quite self-critical about the performance. He later admitted that he felt miscast. It’s rare for a star of that magnitude to be so honest about a project, but he knew the silhouette he cut didn't match the ghost of the character Tolstoy wrote.

Technical Feats of the 1956 Epic

Despite the casting oddities, you have to give the film credit for its technical ambition. This was the era of the "Super-Spectacle." Cinema was fighting against the rise of television, so movies had to be bigger, louder, and longer.

✨ Don't miss: Love Island UK Who Is Still Together: The Reality of Romance After the Villa

The Battle of Borodino sequence is still impressive. They used over 60 cannons. They had to coordinate thousands of people without headsets or digital timing. If a horse tripped in the background of a shot, they couldn't just "fix it in post." They had to reset the whole thing.

The costumes were another feat. They produced thousands of authentic 19th-century military uniforms. The attention to detail in the ballrooms and the winter retreats is genuine. It’s a beautiful film to look at, even if you have to squint to believe Henry Fonda is a Russian youth.

Finding the Value in the 1956 Version Today

So, why should anyone watch the 1956 War and Peace now?

Honestly, it’s a fascinating time capsule. It represents the height of the Hollywood studio system’s ego. It’s also the only way to see Audrey Hepburn in a role that she was arguably destined to play. Her Natasha is vibrant, heartbreaking, and perfectly captures the transition from girlhood to the harsh realities of war.

For fans of Henry Fonda, it’s an essential watch because it shows the limits of a great actor. Even the best have boundaries. Watching him navigate a role that is diametrically opposed to his "type" is a lesson in craft. He doesn't phoning it in; he’s trying hard. Sometimes, watching a great artist struggle is more interesting than watching them succeed effortlessly.

- Watch for the visuals: If you have a big 4K screen, the VistaVision restoration is genuinely gorgeous.

- Compare the adaptations: Watch an hour of this, then an hour of the 2016 BBC miniseries or the 1966 Soviet version. The differences in how Pierre is handled are wild.

- Appreciate the score: Nino Rota (who did The Godfather) wrote the music. It’s sweeping and tragic and far better than the movie often deserves.

The film is currently available on several streaming platforms and is a staple for TCM viewers. It’s one of those movies that you don't necessarily "enjoy" in the traditional sense, but you respect the sheer audacity of its existence.

What You Can Learn from the Henry Fonda Pierre Bezukhov Debacle

If you’re a film buff or a student of acting, the biggest takeaway from the war and peace henry fonda saga is the importance of "essence" over "skill." Fonda had all the skill in the world, but his essence was wrong for Pierre.

🔗 Read more: Gwendoline Butler Dead in a Row: Why This 1957 Mystery Still Packs a Punch

In modern filmmaking, we see this all the time—big stars cast in roles just to secure funding, regardless of whether they fit the part. Sometimes it works (think Heath Ledger as the Joker), and sometimes it’s Henry Fonda in a girdle.

To truly appreciate this era of filmmaking, look into the production diaries of King Vidor. He struggled with the producers constantly, who wanted more romance and less of the "boring" philosophical musing that makes the book famous. The result is a film that is essentially a high-budget soap opera set against the backdrop of the Napoleonic Wars.

Final Steps for the Dedicated Cinephile

If you want to go deeper into the history of this specific production, here is how to spend your weekend. First, track down the book Audrey and Bill by Edward Z. Epstein; it gives a lot of behind-the-scenes context on the filming in Italy. Next, watch the duel scene in the 1956 film and then read the corresponding chapter in the book. The disparity is fascinating.

Finally, don't dismiss Fonda's Pierre entirely. In the final third of the film, when Pierre is a prisoner of the French, Fonda’s age actually starts to work for him. He looks weary, broken, and wise. In those moments, he finally catches up to the character, and for a few scenes, the casting makes perfect sense.

The lesson here is simple: great art often comes from friction. The friction between a midwestern icon and a Russian epic created a flawed, beautiful, and endlessly debatable piece of cinema history. It’s not perfect, but it’s definitely not boring.

Check the "Special Features" on the Blu-ray if you can find it. There is some incredible footage of the sheer scale of the Italian sets that really puts modern green-screen productions to shame. Seeing those thousands of extras in the mud makes you realize just how much sweat went into making this "failure."

- Research the 1956 production locations: Many of the Italian villas used are still standing and can be visited.

- Compare Rota’s score: Listen to the "Natasha’s Waltz" theme separately; it’s one of the best pieces of mid-century film music.

- Read the King Vidor interviews: The director was famously frustrated by the editing process, and his insights explain why the pacing feels so erratic.