Let’s be real for a second. Most 19th-century poetry feels like a chore. It’s often stiff, formal, and buried under so many layers of "thee" and "thou" that you need a translator just to figure out if the author is talking about a bird or their existential dread. But then there’s Walt Whitman. When he first self-published Leaves of Grass in 1855, it wasn't just a book; it was a physical assault on the literary establishment. At the center of that explosion was the Walt Whitman poem Song of Myself.

It’s huge. It’s messy. It’s loud.

Whitman didn't care about your rhyming couplets. He didn't care about "proper" decorum. He wanted to write a poem that was as big and chaotic as America itself. Honestly, if you read it today, it still feels more modern than half the stuff on contemporary bestseller lists. He starts by saying, "I celebrate myself, and sing myself," which sounds incredibly narcissistic until you realize he’s actually trying to invite the entire universe into his own skin. He’s not just talking about Walt; he’s talking about you, the dirt under your fingernails, the stars, and the guy selling newspapers on the corner.

The Scandalous Birth of a Masterpiece

When the 1855 edition dropped, people were genuinely confused. Some were offended. Ralph Waldo Emerson famously sent Whitman a letter praising the work as "the most extraordinary piece of wit and wisdom that America has yet contributed," but others thought it was straight-up trash. Critics called it "reckless" and "sensual." Why? Because Whitman dared to talk about the body in a way that wasn't shrouded in Victorian shame.

He wrote about the "scent of these arm-pits" being "aroma finer than prayer." Think about that. In 1855, comparing body odor to a religious experience was a bold move. It was borderline blasphemous. But the Walt Whitman poem Song of Myself wasn't trying to be edgy for the sake of it. Whitman believed that the physical and the spiritual were the same thing. To him, the soul wasn't some ghostly vapor trapped in a cage of ribs; it was the ribs. It was the skin.

He was a printer by trade, a journalist, and a nurse during the Civil War. He saw bodies at their most vital and their most broken. This wasn't some ivory tower academic writing about abstract concepts. This was a man who lived in the streets of Brooklyn and New Orleans, soaking up the "viva" of the crowds.

Why the 52 Sections Matter (and Why They Don't)

You'll notice the poem is usually broken into 52 sections. That didn't happen right away. Whitman was a notorious tinkerer. He spent his whole life rewriting Leaves of Grass, adding poems, deleting them, and re-shuffling the order. The version of "Song of Myself" we usually read in college is from the 1892 "Deathbed Edition."

The 52 sections sort of represent the weeks in a year, a full cycle of life. But honestly? Don't get hung up on the numbering. The poem is a stream of consciousness before that was even a "thing" in literature. It moves from a blade of grass to a runaway slave, to an opera singer, to a group of young men bathing in a river. It’s a montage.

👉 See also: The Entire History of You: What Most People Get Wrong About the Grain

That "Grass" Metaphor Everyone Remembers

Probably the most famous part of the Walt Whitman poem Song of Myself is Section 6. A child asks, "What is the grass?" and Whitman realizes he doesn't have a simple answer. He calls it the "handkerchief of the Lord," or maybe the "produced babe of the vegetation."

My favorite interpretation he gives, though, is that grass is "the beautiful uncut hair of graves." It's a bit macabre, sure. But it’s also deeply hopeful. He’s saying that death isn't an end. It’s just a recycling program. The atoms of the dead become the nutrients for the grass, which we then walk on and breathe in.

- The Individual vs. The Collective: Whitman argues you can be a unique person while still being part of everyone else.

- Democratic Vistas: He truly believed poetry could save democracy by making people see themselves in their neighbors.

- The Body Electric: He celebrates sex, digestion, and sweat as holy acts.

It’s a very "no gatekeeping" approach to spirituality. You don't need a priest or a temple. You just need to look at a leaf of grass or your own hand.

The "Do I Contradict Myself?" Moment

We’ve all seen the memes or the Pinterest quotes. "Do I contradict myself? Very well then I contradict myself, (I am large, I contain multitudes.)"

People use this today to justify being flaky or changing their minds, but for Whitman, it was deeper. He was acknowledging that the human experience is too vast to be consistent. We are all walking contradictions. We are both selfish and kind. We are both animalistic and divine. In the Walt Whitman poem Song of Myself, he gives us permission to be messy. He’s telling us that you don't have to be one "thing" for your whole life.

It’s a rejection of the "branding" culture we live in today. Whitman didn't have a "niche." His niche was existence.

Whitman as the Original "Influencer"

If Whitman were alive today, he’d probably be banned from half the social media platforms for his "oversharing," but he’d also have a massive following. He was his own PR agent. He wrote anonymous reviews of his own book, calling himself a "bearded, sun-burnt, free-living" genius.

✨ Don't miss: Shamea Morton and the Real Housewives of Atlanta: What Really Happened to Her Peach

He understood the power of the image. That famous engraving in the 1855 edition—where he’s standing with one hand on his hip, wearing a hat, shirt unbuttoned—was a deliberate choice. He wanted to look like a working man, not a scholar. He wanted the Walt Whitman poem Song of Myself to feel like a conversation you're having with a guy on a ferry, not a lecture in a classroom.

Confronting the Difficult Parts

We can't talk about Whitman without acknowledging that he’s complicated. While "Song of Myself" is a masterpiece of radical inclusion—where he explicitly puts himself in the shoes of a "hounded slave" and feels the "twinges" of their pain—Whitman’s personal politics were sometimes a mess.

He was a product of the 19th century. Despite his poetic empathy, he often struggled with the actual political realities of abolition and racial equality in his prose writings. Some scholars, like David Reynolds, argue that his poetry was a way to transcend the fractured politics of his time. He was trying to find a "mystical union" for a country that was literally tearing itself apart.

Does that make the poem less powerful? No. It makes it human. It shows that even a person capable of writing the most inclusive poem in history can still have blind spots. It’s another one of those "multitudes."

How to Actually Read This Poem Without Getting Bored

Don't try to read it like a novel. You'll get tired. The Walt Whitman poem Song of Myself is best consumed in chunks.

- Read it aloud. Seriously. Whitman wrote in "cadences." It’s based on the rhythm of the Bible and the rhythm of the sea. If you read it silently, you miss the music.

- Skip around. If a section isn't hitting for you, move to the next one. He’s not building a linear argument. He’s painting a mural.

- Ignore the "theories." You don't need a PhD to understand "I loaf and invite my soul." He’s literally just talking about hanging out and being present.

- Look for the "Lists." Whitman loves a good list. He’ll list off thirty different jobs people do in New York. Instead of reading it as a boring inventory, read it as a fast-paced camera pan through a city.

The Lasting Legacy of the "Barbaric Yawp"

Toward the end of the poem, Whitman describes himself as "not a bit tamed" and says, "I sound my barbaric yawp over the roofs of the world."

That "yawp" has echoed through everything. You hear it in the Beat Poets of the 1950s—Allen Ginsberg’s "Howl" is basically a 20th-century remix of "Song of Myself." You hear it in the lyrics of Bob Dylan and Kendrick Lamar. You see it in every artist who refuses to fit into a neat little box.

🔗 Read more: Who is Really in the Enola Holmes 2 Cast? A Look at the Faces Behind the Mystery

Whitman's work changed the definition of what poetry could be. He broke the line. He got rid of the meter. He made the language of the common person "literary."

Actionable Steps for Deepening Your Understanding

If you want to move beyond just reading the words and actually feel what Whitman was getting at, here is how you can engage with the text more deeply.

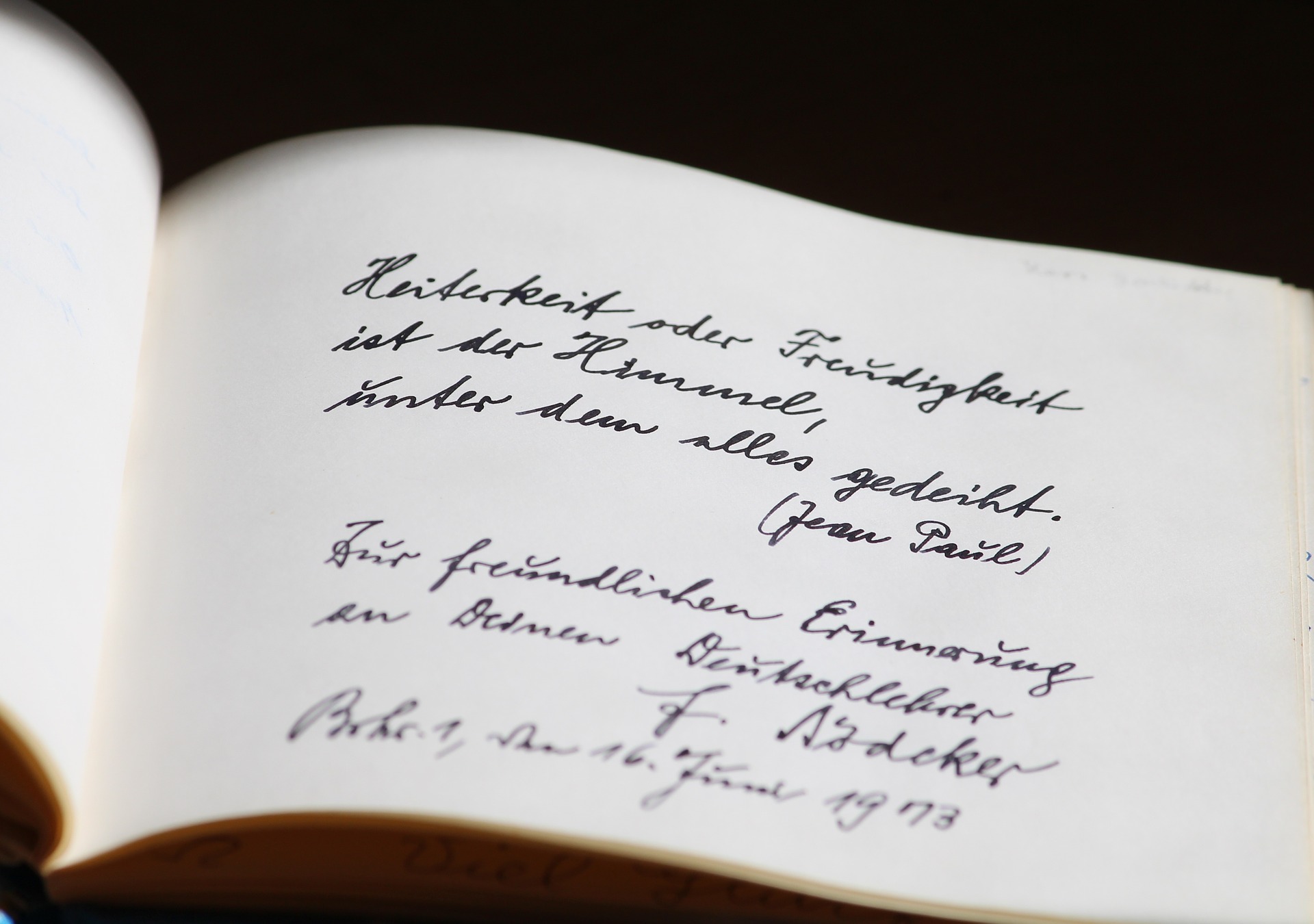

Visit the Whitman House or the Archive: If you're near Camden, New Jersey, go to his final home. If not, the Walt Whitman Archive online is a goldmine. You can see his actual messy handwriting and the different versions of the poem as it evolved over decades. Seeing the physical corrections makes the "Song of Myself" feel much more real and less like a static monument.

Write Your Own "Catalog": One of Whitman’s main techniques is the "catalog"—a long list of observations. Try writing your own for 10 minutes. Don't filter. List what you see out your window, what you're feeling, the noises in the street. It’s a meditative exercise that helps you see the world through his "democratic" lens.

Compare the 1855 vs. 1892 Versions: Pick a specific section, like Section 11 (the "twenty-eight young men" bathing), and see how it changed. The earlier versions are often rawer and more urgent, while the later ones are more polished. Deciding which you prefer will help you find your own "voice" as a reader.

Listen to a Professional Reading: Find a recording of the actor Orson Welles or Galways Kinnell reading the poem. Hearing a powerful voice handle the "barbaric yawp" can unlock the rhythm in a way that reading off a screen or paper simply cannot.

Ultimately, the Walt Whitman poem Song of Myself is a challenge. It’s a challenge to stop being small. It’s a challenge to stop being afraid of your own body and your own contradictions. It’s an invitation to join the "long brown path" and realize that you, whoever you are, are "much ampler than you thought."