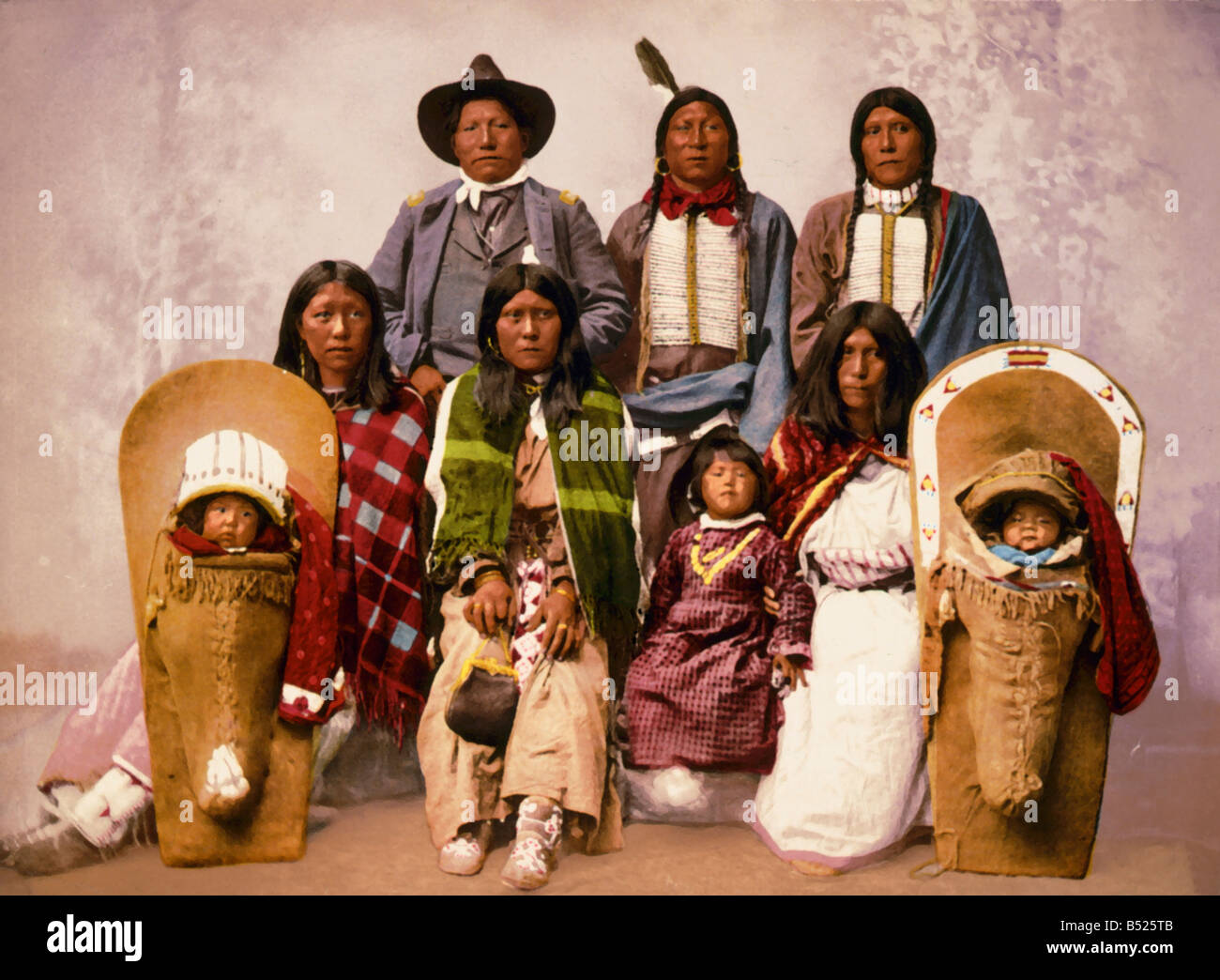

Honestly, looking at vintage photos of Native Americans can be a bit of a trip. You see these stoic faces, the intricate beadwork, and the heavy feathered headdresses, and it feels like you're peering directly into a lost world. But there's a catch. A lot of what we see in these grainy sepia prints wasn't exactly a "candid" moment. It was a production.

If you've ever spent time browsing the archives of the Library of Congress or scrolling through museum digital collections, you've definitely seen the work of Edward S. Curtis. He’s the big name. The giant. Between 1907 and 1930, Curtis took over 40,000 photos for his massive project, The North American Indian. It was funded by J.P. Morgan and backed by Theodore Roosevelt. It was supposed to be the definitive record of a "vanishing race."

But here’s the thing.

The people weren't vanishing. Their cultures were being systematically suppressed, sure, but the "doomed" narrative was something white audiences in the early 20th century were obsessed with. To make the photos fit that narrative, Curtis sometimes carried a box of "authentic" props—wigs, clothes, even baskets—to ensure the subjects looked the way he thought they should look. If a Piegan man showed up in a modern (for 1900) jacket or wearing a clock on his wall, Curtis would often edit it out or ask him to remove it. He wanted a version of the past that was already gone.

The Problem with the "Noble Savage" Lens

When we talk about vintage photos of Native Americans, we have to talk about the power dynamic behind the lens. Most of these photographers weren't Indigenous. They were outsiders coming in with a specific artistic or scientific agenda. This created a bit of a distorted mirror.

Take the "stoic Indian" trope. You know the look—unblinking eyes, no smile, looking off into the distance. People used to think Native Americans just didn't have a sense of humor or were naturally "stony." Total nonsense. In reality, early photography required long exposure times. You couldn't just snap a shot on an iPhone; you had to sit perfectly still for seconds, sometimes longer. If you moved, the photo was ruined. Try holding a grin for thirty seconds without looking like a creep. It’s hard. Plus, many of these individuals were being photographed by representatives of the very government that was actively displacing them. Why would they be smiling?

💡 You might also like: Cooper City FL Zip Codes: What Moving Here Is Actually Like

There’s also the issue of "ethnographic taxidermy." This is a term some scholars use to describe how photographers like Joseph K. Dixon or Gertrude Käsebier tried to "freeze" Indigenous people in time.

Why the context of the 1890s matters

The late 19th century was a brutal time. The Wounded Knee Massacre happened in 1890. The boarding school system was in full swing, forcibly removing children from their homes to "kill the Indian, save the man." So, while the government was trying to erase the culture in real life, photographers were rushing to capture it in photos. It’s a weird, painful irony. You have these beautiful, high-contrast images of a culture being celebrated as "art" at the exact same moment it was being persecuted as "primitive" by the law.

Identifying Real History vs. Staged Art

If you want to get good at reading these images, you have to look at the details. Look at the clothing. Sometimes you’ll see a photo labeled as "Apache Warrior," but the guy is wearing a Crow-style headdress because the photographer thought it looked "more Indian." It happened all the time.

Genuine vintage photos of Native Americans—the ones that weren't strictly for a "fine art" book—often show a much more complex reality. Look for the photos taken by people actually living in the communities or the rare Indigenous photographers of the era.

- Jennie Ross Cobb (Cherokee): She started taking photos in the late 1800s. Her pictures are totally different. They show Cherokee women in fashionable Victorian dresses, hanging out on porches, living their actual lives. No staged feathers. No fake gloom.

- Horace Poolaw (Kiowa): Though his work comes a bit later (starting in the 1920s), his photos are a masterclass in reality. He captured Kiowa people in traditional regalia and Kiowa people in military uniforms or playing baseball.

These images break the "museum exhibit" vibe. They show people who were navigating two worlds simultaneously. It’s way more interesting than the staged stuff, honestly.

📖 Related: Why People That Died on Their Birthday Are More Common Than You Think

The Technical Side: Tintypes, Cyanotypes, and Glass Plates

Early photography was a messy, chemical-heavy business. Most of the vintage photos of Native Americans you see from the mid-1800s are daguerreotypes or tintypes.

Daguerreotypes were the first commercially successful photographic process. They’re basically images on highly polished silver-plated copper. They have a mirror-like quality. If you hold one, you have to tilt it just right to see the person. They feel intimate. Because they were expensive, the people in them—whether they were tribal leaders visiting Washington D.C. on treaty business or wealthy mixed-blood families—usually dressed in their absolute best.

Later came the wet plate collodion process. This is where we get those famous glass plate negatives. The photographer had to coat a glass sheet in chemicals, rush it into the camera while it was still wet, take the photo, and develop it immediately in a darkroom tent. It was an athletic feat. This is why many photos of the Old West feel so static—the equipment weighed a ton and the process was incredibly delicate.

Why the colors look "off"

Ever wonder why red looks almost black in old photos? Early photographic emulsions were "orthochromatic." They were super sensitive to blue light but almost blind to red. This means a bright red trade cloth blanket would look dark and moody in a 19th-century photo. It changes how we perceive the vibrancy of the actual clothing. The past wasn't black and white, and it certainly wasn't just shades of brown. It was neon-bright with beads, dyes, and ribbons.

How to Collect and Archive Responsibly

If you’re interested in collecting or even just researching these images, there’s an ethical layer you can’t ignore. These aren't just "cool old pictures." They are ancestors. Many Indigenous communities today are working to reclaim these images through "visual sovereignty."

👉 See also: Marie Kondo The Life Changing Magic of Tidying Up: What Most People Get Wrong

- Check the provenance. Where did the photo come from? If it’s from a reputable archive like the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI), they usually have extensive notes on the tribal affiliation and, if known, the name of the person.

- Respect the sacred. Some vintage photos depict ceremonies or objects that were never meant to be seen by outsiders. Many tribes have requested that photos of certain dances or "medicine" items be removed from public viewing.

- Support Indigenous-led archives. Organizations like the First Nations Development Institute or local tribal museums often have the best context for these images. They can tell you who the person was, not just what they were wearing.

The Modern Impact of Old Images

Why do we still care? Because these photos still shape how people see Native Americans today. If the only images you see are the "tragic" ones from 1900, it’s easy to forget that these nations are vibrant, modern, and very much still here.

There’s a movement now where Indigenous artists "remix" these vintage photos. They take the old, staged images and add color, or they use them to create new art that talks back to the original photographer. It’s a way of taking the power back. They’re saying, "You tried to freeze us in 1904, but we’re still moving."

Actionable Steps for Researching Vintage Photos

If you want to find the real stories behind these images, don't just use Google Images. Go deeper.

- Start with the NMAI Digital Collection. It’s one of the most comprehensive and ethically managed databases in the world. You can search by tribe, which is way more accurate than just searching "Native American."

- Look for the names. Whenever possible, try to find the name of the individual in the photo. Moving from "An Indian Chief" to "Chief Wolf Robe (Cheyenne)" changes the image from a stereotype to a biography.

- Compare photographers. Look at a Curtis photo alongside a Poolaw or a Cobb photo. Notice the differences in how the subjects are posed. Notice what’s in the background. The background often tells the truth that the foreground is trying to hide.

- Verify tribal affiliations. Nineteenth-century photographers were notorious for mislabeling tribes. If a photo says "Sioux" but the beadwork is clearly "Ojibwe," the beadwork is usually right and the photographer was wrong.

- Read the journals. Many photographers kept diaries. Curtis’s assistants often wrote about the "staging" they had to do, which provides a massive amount of context for the final, polished images.

The history of vintage photos of Native Americans is a mix of beautiful artistry and complicated propaganda. By looking at them with a critical eye, you aren't "disrespecting" the art—you're actually respecting the people in the photos more by trying to see who they really were, rather than who the photographer wanted them to be.

Next time you see a "stoic" portrait, look for the small things. A ring on a finger. A slight blur from a breath. A hidden smile in the eyes. That’s where the real history lives. It’s in the details that the photographer forgot to edit out. It's in the humanity that couldn't be contained by a glass plate or a staged backdrop.

Find a specific archive, like the New York Public Library’s Digital Collections, and search for a specific tribe name rather than a general term. Focus on the 1870–1910 period to see the transition from early plates to film. This allows for a more nuanced understanding of how technology and federal policy intersected during the most photographed era of Indigenous history.