History is usually written by the people who kept their clothes on, or at least the ones who made sure the cameras were pointed elsewhere when the buttons came undone. But if you look at the skyrocketing prices at auction houses like Sotheby’s or the sudden influx of archival accounts on Instagram, you’ll notice something. Vintage photos of naked men aren't just "NSFW" relics anymore. They are becoming the primary way we understand how masculinity actually functioned before the internet made everything so self-conscious.

It's a weirdly personal market. People aren't just buying these for the sake of the physique; they’re buying them because a grainy black-and-white shot from 1920 feels more honest than a high-def selfie from 2024.

The Myth of the "Accidental" Archive

Most people assume that old-school photography of the male form was either strictly medical or purely "physique" focused, which was the 1950s code word for "don't tell the post office what's in this envelope." That's not entirely true. While the Comstock Laws in the United States made it a literal crime to send "obscene" materials through the mail, photographers were incredibly clever.

They used the excuse of Greek classicism. If you put a man in a laurel wreath and had him hold a fake lyre, suddenly it wasn't a "naked photo"—it was "Artistic Study in the Hellenic Style."

Take Baron Wilhelm von Gloeden. He’s the guy most historians point to when they talk about the birth of this genre. Working in Taormina, Sicily, in the late 19th century, he photographed local youths in various states of undress. He claimed he was just capturing the "purity of the Mediterranean spirit." In reality, he was creating a massive commercial enterprise. By the time he died, his archive was huge. Then the fascists showed up. In 1936, the Italian police destroyed thousands of his glass plates. What survived did so because private collectors literally hid them under floorboards.

Why We Are Obsessed With the Grain

There is a tactile quality to a silver gelatin print that you just can’t replicate. Digital is too perfect. It shows every pore, every hair, every flaw in a way that feels clinical. But a vintage print? It has "tooth." The shadows are deep, almost liquid.

🔗 Read more: At Home French Manicure: Why Yours Looks Cheap and How to Fix It

Authenticity is the keyword here. When you look at a photograph from the Tom of Finland Foundation or the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, you aren't just looking at a body. You're looking at a moment of risk. Before the 1960s, posing for these photos could get you arrested, fired, or worse. The tension of that risk is baked into the film.

I was talking to a collector recently who spent three years tracking down a specific series of 1940s military "smokers"—those unofficial, often underground boxing matches where soldiers would strip down. He told me that the appeal wasn't the nudity. It was the camaraderie. Men used to be much more physically affectionate with each other before the mid-20th-century "lavender scare" made everyone paranoid about being perceived as "soft." These photos prove that history was a lot more fluid than your high school textbook suggested.

The Business of the Male Physique

Let's talk money because the market for vintage photos of naked men has shifted from the back of the shop to the front of the gallery.

In the mid-20th century, magazines like Physique Pictorial (founded by Bob Mizer in 1945) were the gold standard. Mizer was a pioneer. He started the Athletic Model Guild (AMG) in Los Angeles. He didn't just take pictures; he built an empire. He lived in a house with a rotating cast of models, many of whom were just guys looking for a quick buck or a place to stay.

Today, an original Mizer print or a vintage Physique Pictorial issue can fetch hundreds, sometimes thousands, of dollars. Collectors look for:

💡 You might also like: Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen Menu: Why You’re Probably Ordering Wrong

- The AMG Stamp: Authentic Athletic Model Guild stamps on the back of the photo.

- The Paper Stock: Double-weight fiber paper is the "holy grail" for collectors because it survives the decades better.

- The Context: Candid shots from the 1920s-1940s are often worth more than the professional "physique" shots of the 50s because they are rarer.

It’s not just about the big names like George Platt Lynes or Herbert List either. There is a massive "vernacular" market. Vernacular photography is just a fancy way of saying "snapshots taken by regular people." These are the photos found in flea markets, tucked inside old books, or discovered in estate sales of bachelor uncles. These are the ones that really tell the story of how men saw themselves when they thought no one was looking.

What People Get Wrong About the "Good Old Days"

There’s this idea that everyone back then was repressed. Honestly? It's the opposite.

If you look at YMCA photography from the early 1900s, naked swimming was the standard. It wasn't sexualized; it was just... what men did. The "sexualization" of the male body actually led to more clothes being worn in public spaces, not fewer. When we look at vintage photos of naked men from that era, we’re often seeing a level of comfort with the male form that we’ve actually lost in the modern age.

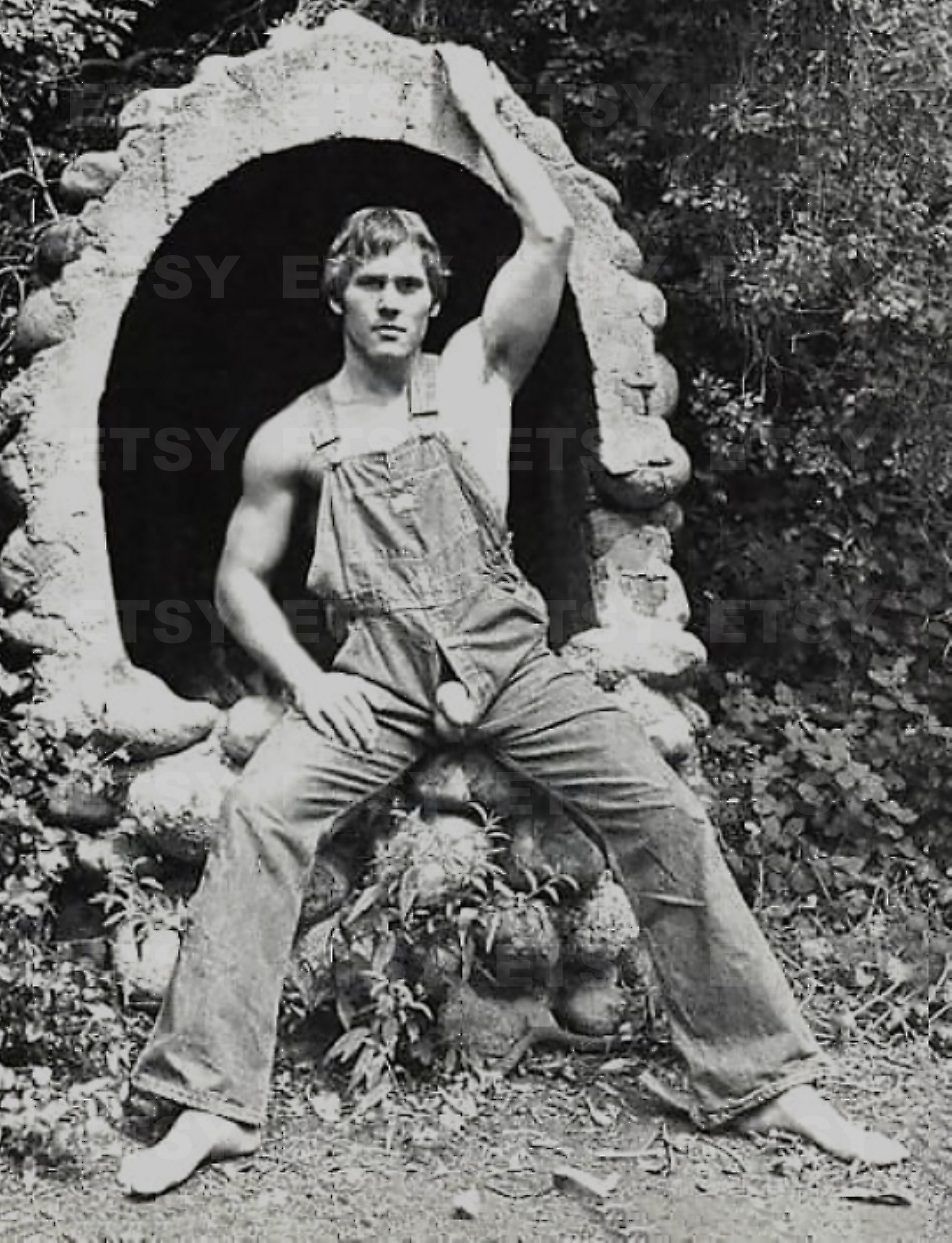

We’ve traded casual nudity for hyper-manicured, gym-rat perfection. The men in vintage photos usually don't have six-packs. They have "dad bods" before that was a term. They have hair. They have scars. They look like people, not statues. That’s why these images are so popular on social media right now—they offer an escape from the "filter" culture that makes everyone feel inadequate.

How to Start Your Own Collection (The Right Way)

If you’re looking to get into this, don't just go to eBay and search for "old naked guy." You’ll get a lot of modern reprints that are worth exactly zero dollars.

📖 Related: 100 Biggest Cities in the US: Why the Map You Know is Wrong

First, learn the difference between a "vintage print" and a "modern print." A vintage print was made around the same time the photo was taken. A modern print (or "later print") was made years later from the original negative. The vintage one is where the value lies.

Second, check the edges. Silver mirroring—that shiny, metallic sheen that appears in the dark areas of an old photo—is actually a good sign. It happens as the silver in the print oxidizes over 50 or 60 years. It’s the "patina" of photography.

Third, focus on a niche. Some people only collect 19th-century tintypes. Others want 1970s Polaroids because of that specific, dreamy color palette. The 1970s was a huge turning point because of the 1969 Stonewall riots; the photography became bolder, more defiant, and much more "out."

A Note on Ethics and Preservation

We have to acknowledge the dark side. Not everyone in these old photos wanted to be there, and many were exploited. When you’re dealing with historical archives, it’s important to treat the subjects with some level of dignity. These aren't just "assets." They are people.

If you find a cache of old photos, don't just post them all online immediately. Research the context. If you have physical prints, keep them out of direct sunlight. UV rays are the enemy. Acid-free sleeves are your best friend.

Ultimately, the surge in interest in vintage photos of naked men says more about us than it does about them. We are hungry for a version of masculinity that feels unscripted. We want to see the men who lived through the wars, the depressions, and the quiet decades, and realize they weren't so different from us. They were just as vain, just as proud, and just as human.

To build a meaningful collection or archive, start by visiting the digital collections of the Kinsey Institute or the New York Public Library’s digital archives. Compare what you see there to what is being sold in "lot" auctions on sites like LiveAuctioneers. Identifying the paper type and the specific lighting styles of the 1930s versus the 1950s is the first step in moving from a casual observer to a serious historian of the form. Use archival-grade storage boxes immediately—never use "magnetic" photo albums from the 90s, as the adhesive will destroy the emulsion within a few years. Record any provenance information you find on the back of the prints using a soft 6B pencil, never a ballpoint pen. Preservation is the only way these stories survive another century.