Pixels are exhausting. If you’ve ever tried to scrub through a 4K security feed looking for a specific face, or wondered how a self-driving car distinguishes a blowing plastic bag from a toddler, you’ve felt the weight of raw data. This is where the video convolutional neural network (VCNN) steps in. It isn't just a regular image-recognition tool on a treadmill. It’s a specialized architecture designed to understand that time is just as important as space.

Most people get AI vision wrong. They think the computer sees a movie the way we do—as a fluid story. In reality, a standard computer sees a video as a stack of disconnected photos. That's why traditional CNNs, which revolutionized image tagging for Google Photos or Instagram, often fail miserably when things start moving. A VCNN changes the game by treating "time" as a third dimension. It’s the difference between looking at a flipbook one page at a time and seeing the whole stack of paper at once.

The Spatiotemporal Nightmare: Why 2D Just Doesn't Cut It

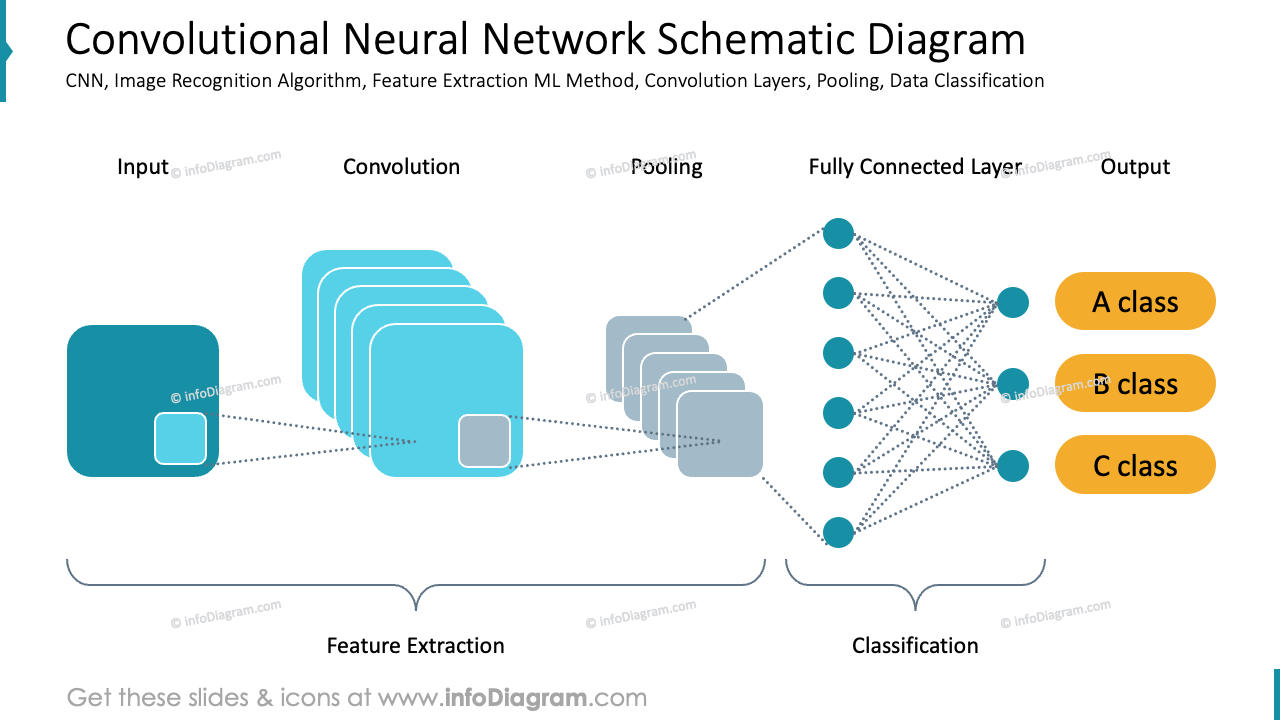

A standard 2D CNN looks at height and width. You feed it a picture of a cat, it finds the ears, the whiskers, and the tail, and boom—it’s a cat. But try asking that same model to identify "running" versus "tripping." Both involve a body in mid-air with limbs flailing. To a 2D network, these two very different events look nearly identical in a single frame.

This is the core problem of temporal coherence. Video convolutional neural networks solve this by using 3D kernels. Instead of a little square sliding across a flat image, you have a cube sliding through a block of video frames. This cube captures spatial features (like the shape of an object) and temporal features (how that shape changes over five or ten frames) simultaneously. It’s heavy. It’s computationally expensive. Honestly, it’s a bit of a hardware nightmare, but it’s the only way to get true "action recognition."

Think about the C3D model (Convolutional 3D) developed by researchers at Facebook AI Research (FAIR) and Dartmouth. When it debuted, it was a revelation because it proved that simple 3D convolutions could outperform complex hand-crafted features. It wasn't perfect, though. The sheer number of parameters in a 3D network is staggering. While a 2D network might have millions of parameters, a 3D version can easily balloon into the hundreds of millions, requiring massive amounts of VRAM.

The Breakdown of Motion

You can't talk about these networks without mentioning "Optical Flow." Some researchers, like those behind the Two-Stream Fusion networks (Simonyan and Zisserman), decided that one network wasn't enough. They built one stream to look at the raw frames (the "what") and a second stream to look at the motion displacement between frames (the "how"). They then fused these two together. It’s basically teaching a computer to see the world like a hunter—one eye for the colors and shapes, and another eye that only detects movement in the brush.

Real-World Chaos and Where These Models Actually Live

It’s not all academic papers and benchmarks like Kinetics-400 or UCF101. These models are actually out there doing grunt work. Take medical imaging. Doctors are using video convolutional neural networks to analyze ultrasound videos. A single still of a heart might look fine, but a VCNN can detect a slight hiccup in the rhythmic wall motion that suggests a future stroke. It’s analyzing the "beat," not just the "image."

Then there's the world of autonomous sports broadcasting. Companies like Pixellot use these architectures to track a soccer ball in real-time. The AI has to predict where the ball is going based on its current trajectory and the body language of the players. If the network only looked at individual frames, the camera would be jerky and laggy. Because it understands the temporal flow, the camera movement is smooth—almost human.

The Efficiency Wall

We have to be real here: these things are slow. If you tried to run a full-scale 3D VCNN on your smartphone, the battery would probably melt through the casing. This has led to some clever engineering workarounds like (2+1)D convolutions. Instead of a full 3D filter, researchers split it into a 2D spatial convolution followed by a 1D temporal convolution. It's basically a "cheat code" that gives you most of the accuracy of 3D with a fraction of the processing power.

🔗 Read more: Why The Little Book of Deep Learning is the Only AI Text You’ll Actually Finish

You've also got the "SlowFast" network approach from FAIR. It's brilliant in its simplicity. One pathway (the Slow one) operates at a low frame rate to capture high-resolution spatial detail. The other pathway (the Fast one) operates at a high frame rate but with very low resolution to capture fast-moving motion. It mimics the human visual system's parvocellular and magnocellular cells. Nature already solved this problem; we’re just finally catching up with silicon.

The Problem With "Memory" and Long Videos

A huge misconception is that a video convolutional neural network can "watch" a movie. It can’t. Most of these models have a memory span of about 2 to 5 seconds. If a guy enters a room in minute one and leaves in minute ten, a standard VCNN has no idea it’s the same guy. It has "short-term memory" but lacks "narrative understanding."

To fix this, engineers are starting to marry VCNNs with Transformers. While the CNN part handles the heavy lifting of identifying pixels and textures, the Transformer part handles the long-range dependencies. This is the cutting edge. This is what allows an AI to understand a complex recipe video where "adding salt" at the end only makes sense if it saw "boiling water" at the beginning.

Why Researchers are Moving Away from "Pure" Convolutions

There’s a bit of drama in the AI world right now. The "Vision Transformer" (ViT) is threatening to dethrone the CNN entirely. Some argue that convolutions are too rigid—that the "sliding window" approach is too localized. They want models that can look at the whole frame at once using "Self-Attention."

However, VCNNs aren't dying. They are evolving. Convolutions are incredibly efficient at finding edges and textures—things Transformers struggle with unless they have massive amounts of training data. Most modern systems are actually hybrids. They use a VCNN as a "front-end" to process the raw pixels and then hand those features off to a Transformer to figure out the "story" of the video.

Actionable Insights for Implementing Video AI

If you’re looking to actually use a video convolutional neural network for a project or business, you shouldn't start from scratch. That's a recipe for burning through your cloud budget in forty-eight hours.

- Leverage Pre-trained Models: Start with models pre-trained on the Kinetics-700 dataset. These networks already "know" what 700 human actions look like. You just need to fine-tune the last layer for your specific task.

- Prioritize (2+1)D Architectures: Unless you have a cluster of H100 GPUs, avoid pure 3D convolutions. The performance-to-cost ratio of (2+1)D is significantly better for most commercial applications.

- Optimize Your Data Pipeline: Video is heavy. Use libraries like PyVideoFrames or NVIDIA's DALI to decode video directly on the GPU. If you're decoding on the CPU and then moving data to the GPU, your model will be sitting idle 90% of the time.

- Think About Temporal Scale: Does your AI need to recognize a "sneeze" (0.5 seconds) or a "store robbery" (5 minutes)? Match your frame-sampling rate to the action. Don't process 60 frames per second if the action you're looking for takes 10 seconds to unfold.

The reality is that video convolutional neural networks are the workhorses of the modern visual web. They are the reason YouTube can flag copyrighted content almost instantly and the reason your "Smart Home" camera doesn't ping you every time a shadow moves. We are moving toward a world where "blind" machines are a thing of the past. It’s no longer about just seeing; it’s about understanding the sequence of life.

To get started with your own implementation, explore the PyTorch Video library (PyTorchVideo). It contains standardized implementations of the architectures mentioned here, like SlowFast and I3D, which allow you to experiment with temporal modeling without needing a PhD in linear algebra. Testing these models on a small, labeled subset of your own data is the only way to truly understand the trade-offs between speed and spatial accuracy.