Go to any Mexican wedding. Wait for the tequila to hit that middle-of-the-bottle mark. You’ll hear it. That piercing, operatic trumpet intro that feels like a lightning bolt to the chest. Then, the voice. It’s gravel and velvet all at once. It’s Chente. For many, Vicente Fernández canciones viejitas aren't just tracks on a playlist; they are the literal soundtrack to grief, celebration, and masculine identity across three generations.

He wasn’t just a singer. He was El Rey.

But why do these specific "viejitas"—the oldies from the 70s and 80s—hold more weight than the polished hits of the 2000s? It’s about the raw production. Back then, CBS Records (which became Sony) recorded these with a wall of sound that felt massive. You could hear the fingers sliding on the guitar strings. You could hear him take a breath. It was human.

The Raw Power of the Early Years

Honestly, if you haven’t screamed the lyrics to "Tu Camino y el Mío" while clutching a lime, have you even lived? This track, released in the late 60s, set the template. It wasn't just about singing; it was about the grito. That iconic Mexican yell that signals a release of soul.

Chente’s early work was different from the romantic crooning of Javier Solís or the playful wit of Jorge Negrete. Fernández brought a working-class grit to the genre. He was the "Hijo del Pueblo." When he sang about betrayal in "Que Te Vaya Bonito," written by the legendary José Alfredo Jiménez, he wasn't just performing a song. He was exorcising a demon.

People often forget that Vicente didn't become a superstar overnight. He struggled in Mexico City, singing for tips in Plaza Garibaldi. That struggle is baked into the DNA of Vicente Fernández canciones viejitas. You can hear the hunger. By the time he released "El Rey" in 1973, he wasn't just a singer anymore. He was a cultural titan.

The lyrics are simple, yet they hit like a ton of bricks. "Yo sé bien que estoy afuera / pero el día que yo me muera / sé que tendrás que llorar." It’s pure bravado. It’s the anthem of the underdog who knows his worth even when he has nothing. That’s the magic.

📖 Related: Who is Really in the Enola Holmes 2 Cast? A Look at the Faces Behind the Mystery

Why "Volver Volver" Changed Everything

If there is a "Big Bang" moment for ranchera music, it’s 1972. The song was "Volver Volver."

Before this, ranchera was popular, sure. But "Volver Volver" turned it into a global phenomenon. It’s a song about regret, plain and simple. We’ve all been there—wanting to go back to a love we messed up. But Chente’s delivery? It’s agonizing. He stretches those notes until they bleed.

The interesting thing about "Volver Volver" is that it actually broke the "macho" mold. It allowed men to cry. In a culture where "los hombres no lloran," Vicente gave men permission to sob into their beer. It was revolutionary.

The Songs That Defined the Golden Era

- "La Ley del Monte": This is basically a three-minute movie. Two lovers carving their names into a maguey plant. It’s nostalgic, rural, and incredibly vivid. It captures a Mexico that was already disappearing when it was recorded.

- "De Qué Manera Te Olvido": Written by Federico Méndez. This is perhaps his most "perfect" vocal performance. It’s controlled. It’s elegant. It’s the song you play when the party is winding down and everyone is feeling sentimental.

- "Cruz de Olvido": The metaphor of the "cross of oblivion" is heavy. It’s about leaving someone you love because you know you’re bad for them. Heavy stuff for a Sunday afternoon BBQ, right? But that’s the appeal.

The "Viejitas" vs. The New Stuff

Don’t get me wrong. "Estos Celos" from 2007 is a banger. Joan Sebastian wrote a masterpiece there. But there is a specific texture to the Vicente Fernández canciones viejitas from the analog era that digital recording just can't mimic.

In the 70s, the mariachi arrangements were deeper. The violins had a certain "scratch" to them. The trumpets weren't perfectly tuned in a computer; they were played by guys who had been standing in the sun all day. This imperfection is what makes the old songs feel "real."

Also, look at the songwriting. Vicente leaned heavily on the works of José Alfredo Jiménez and Juan Gabriel. These guys were poets of the gutter. They wrote about the reality of the Mexican experience—poverty, honor, unrequited love, and the dignity of the laborer.

👉 See also: Priyanka Chopra Latest Movies: Why Her 2026 Slate Is Riskier Than You Think

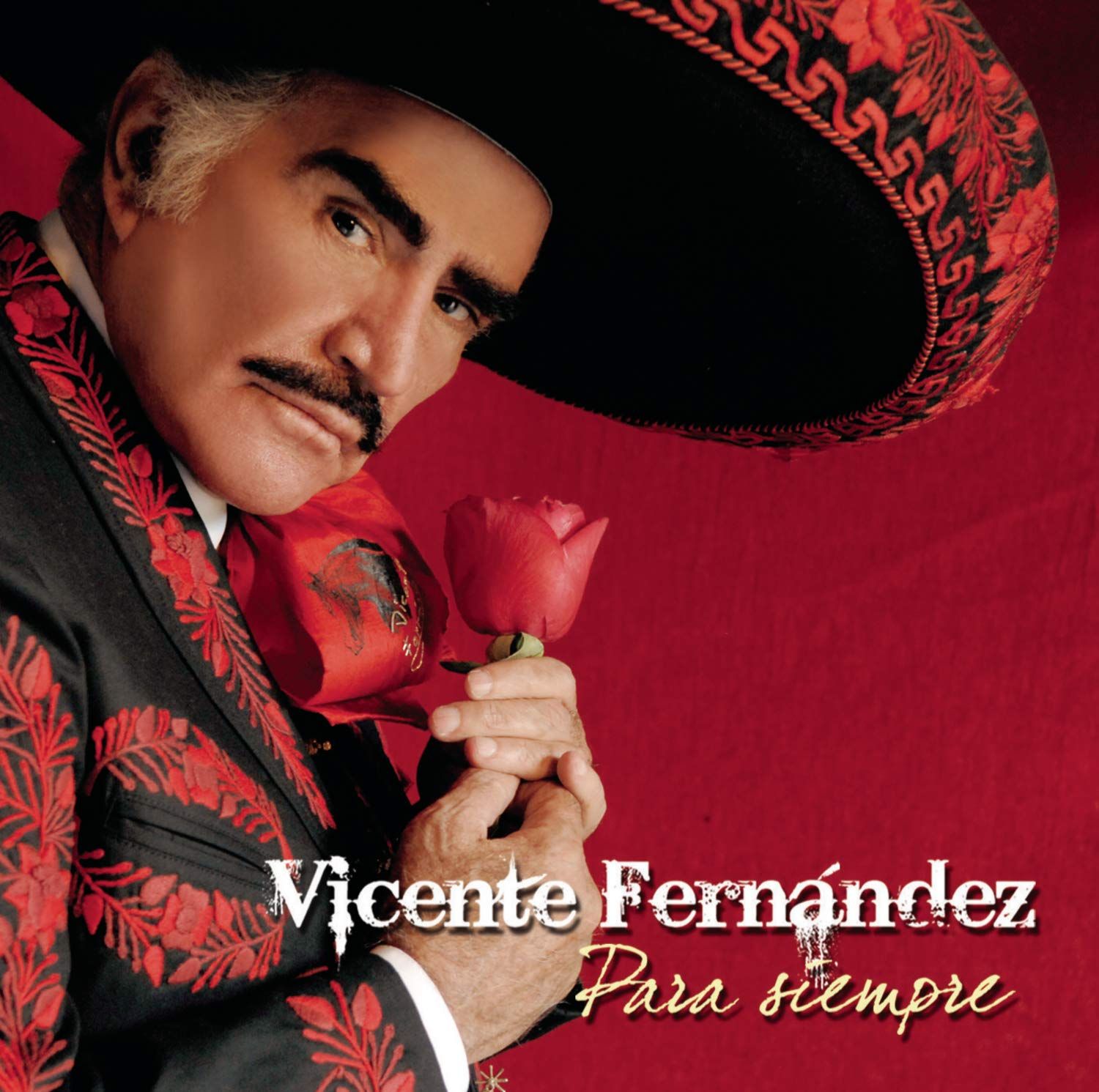

The Myth of the Charro

Vicente Fernández wasn't just a voice; he was a costume. The traje de charro. The oversized sombrero. The pistol on the hip. When you listen to his old songs, you’re looking at a symbol of Mexicanidad.

He famously said, "Mientras ustedes no dejen de aplaudir, su Chente no deja de cantar." (As long as you don't stop clapping, your Chente won't stop singing.) This wasn't a marketing slogan. He would literally perform for four hours straight.

His "viejitas" represent that stamina. They are long, winding narratives. Songs like "Por Tu Maldito Amor" (technically a late 80s hit, but often grouped with the classics) show his ability to build tension. He starts almost in a whisper and ends in a full-throated roar.

The Sound of Nostalgia in 2026

It’s weirdly fascinating how these songs have migrated to TikTok and Instagram. You see 20-year-olds in Los Angeles or Mexico City using "Hermoso Cariño" for their "Get Ready With Me" videos.

Why? Because the emotion is undeniable. In an era of synthesized beats and AI-generated melodies, a man screaming about his heart breaking over a 12-piece brass band feels authentic. It’s an anchor.

How to Properly Appreciate the Classics

To truly "get" these songs, you have to understand the context of the Palenque. These were cockfighting rings where Vicente performed in the round, surrounded by thousands of people, inches away from the crowd.

✨ Don't miss: Why This Is How We Roll FGL Is Still The Song That Defines Modern Country

There was no lip-syncing. No Auto-Tune. If his voice cracked, the whole world heard it. That’s why the old recordings have so much life. They were often captured in few takes to preserve the energy.

If you're building a playlist, don't just go for the hits. Look for the "B-sides" like "Las Llaves de mi Alma" or "Que Te Vaya Bonito." These songs carry the same weight but haven't been overplayed to death on the radio. They still feel like a secret you're sharing with your grandfather.

The Enduring Legacy

Vicente Fernández passed away in 2021, but the "viejitas" are arguably more popular now than they were ten years ago. They have become a cultural shorthand for "home." For the millions of Mexicans living outside of Mexico, these songs are a bridge.

When you hear "México Lindo y Querido," it’s not just a song; it’s a prayer.

The sheer volume of his discography is intimidating—over 80 albums. But the core remains those tracks from the mid-70s. That’s where the soul of the Charro lives. It’s where the trumpets sound the brightest and the heartbreak feels the most permanent.

Actionable Ways to Experience Chente Today

- Listen to the "En Vivo" albums: Specifically the recordings from the 80s. The crowd interaction adds a layer of energy that studio albums lack.

- Watch the movies: Many of his most famous "viejitas" were title tracks for his films. Watching him perform "La Ley del Monte" in the context of the movie gives the lyrics a whole new meaning.

- Check the Songwriters: If you love a specific old song, look up who wrote it. Usually, it’s José Alfredo Jiménez or Martín Urieta. Following the songwriter will lead you to more gems in the same vein.

- Focus on the Mono/Early Stereo Mixes: If you can find original vinyl or high-quality analog transfers, the "viejitas" sound much warmer. The modern "remasters" sometimes compress the audio too much, killing the dynamics of his voice.

The music of Vicente Fernández isn't meant to be "background noise." It demands your attention. It demands a reaction. Whether it's a tear, a shout, or just a second pour of tequila, these songs are designed to make you feel something profoundly human. That is why they will never grow old, even if we call them "viejitas."