Walk into any big-box gym, and you'll see it. Usually tucked away in the corner between the leg press and the lower back extension. It’s the seated abdominal crunch machine, that bulky piece of equipment with the padded handles and the weight stack that looks like it’s doing most of the work for you. Most "hardcore" fitness influencers will tell you it's a waste of time. They’ll say you should stick to hanging leg raises or cable crunches because machines are "unnatural."

Honestly? They're kinda wrong.

While I love a good floor-based circuit, the seated crunch has its place. It’s actually one of the most misunderstood tools in the weight room. People either use it with zero control—flinging the weights around like a pendulum—or they avoid it entirely because they think it’ll make their waist "blocky." Let’s get real about what this machine actually does and how you should be using it if you want real results, not just a sore neck.

The Biomechanics of the Seated Abdominal Crunch Machine

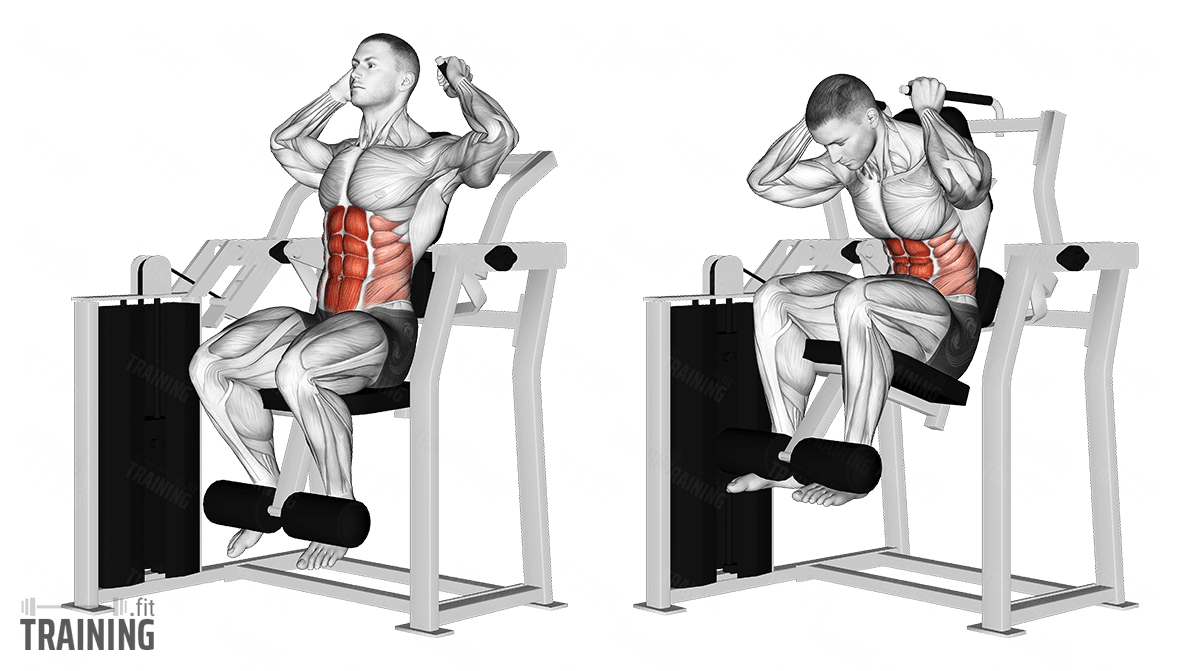

To understand why this machine works, you have to look at the anatomy of the rectus abdominis. That’s your "six-pack" muscle. Its primary job is spinal flexion—bringing your ribcage toward your pelvis. When you’re doing a crunch on the floor, your range of motion is limited by, well, the floor. You hit a flat spot.

The seated abdominal crunch machine changes the game by allowing for a deeper stretch at the top of the movement. Depending on the brand—Life Fitness, Hammer Strength, and Cybex all have slightly different configurations—you can often start in a position of slight spinal extension. This is huge. Muscles grow better when they are challenged through a full range of motion, and that extra bit of stretch at the beginning of the rep is something you just can’t get on a yoga mat.

Think about it this way. You wouldn't do half-reps on a bicep curl and expect huge arms. So why do we settle for limited range on our abs?

Most of these machines use a pivot point that is supposed to align with your spine. This is where most people mess up. If your hips are sliding forward on the seat, you aren't working your abs. You're working your hip flexors. You’ve probably felt that "burn" deep in the front of your hips after a set. That's a sign your psoas is doing the heavy lifting while your abs are just along for the ride. To fix this, you’ve got to glue your lower back to the pad. No daylight. If there's a gap between your lumbar spine and the seat, you're doing it wrong.

Why Load Matters (And Why Your Abs Aren't Different)

There is a weird myth in the fitness world that abs should only be trained with high reps and body weight. People will do 500 crunches a day but wouldn't dream of doing 500 bench presses with just the bar.

📖 Related: Whooping Cough Symptoms: Why It’s Way More Than Just a Bad Cold

Abs are muscles. They respond to mechanical tension. They need progressive overload.

The beauty of the seated abdominal crunch machine is the weight stack. You can actually track your progress. If you did 70 pounds for 12 reps last week and you do 75 pounds today, you got stronger. Period. This is much harder to quantify with floor exercises where "cheating" via momentum is so easy to do without realizing it.

Common Mistakes That Kill Your Gains

Stop pulling with your arms. Seriously.

If you grab those handles and yank with your lats and biceps, your abs are basically on vacation. The handles are there for stability, not for rowing. Try this instead: rest your hands lightly against the pads or hold the handles with a "hook" grip without squeezing. Focus on the distance between your sternum and your belly button. Your goal is to make that distance shorter.

Another big one? Breathing.

Most people hold their breath or take shallow sips of air. If you want a maximal contraction, you have to exhale everything as you crunch down. Think of your lungs like a balloon. If they’re full of air, they’re literally in the way of your abs contracting fully. Empty the tank at the bottom of the rep. It’ll feel twice as hard, but that’s the point.

- The "Hip Flexor" Pull: Using your legs to drive the movement. Keep your feet flat but don't push through them.

- The "Head Nod": Only moving your neck and shoulders while your torso stays upright.

- The "Speed Demon": Moving so fast the weight plates are clanging and jumping.

Slow down. Take two seconds on the way down, hold the squeeze for a full second, and take three seconds to return to the start. The "eccentric" or lowering phase of the movement is where a lot of muscle damage (the good kind) happens. If you’re just letting the weights slam back down, you’re missing half the exercise.

👉 See also: Why Do Women Fake Orgasms? The Uncomfortable Truth Most People Ignore

Is It Better Than a Cable Crunch?

This is the big debate. The cable crunch (the one where you’re on your knees with a rope attachment) is a fantastic exercise. It allows for a lot of freedom of movement. But that freedom is also its weakness. It’s very easy to start using your body weight to "sink" into the rep rather than using your abs to pull.

The seated abdominal crunch machine provides a fixed path of motion. For beginners, or for people who have a hard time "feeling" their abs work, this stability is a godsend. It removes the need to balance or stabilize your entire body, allowing you to put 100% of your focus on the rectus abdominis.

I usually suggest using the machine as a "finisher." After you’ve done your heavy compound lifts or your more difficult stability work like planks or hanging raises, hit the machine. It’s a great way to push the muscle to absolute failure safely.

Real-World Programming

Don't do this every day. Your abs need recovery just like your chest or legs. If you're hitting them with heavy weight on a machine, two to three times a week is plenty.

- For Hypertrophy (Muscle Growth): 3 sets of 10-15 reps. Focus on the "squeeze" at the bottom.

- For Strength/Density: 4 sets of 8-10 reps. Increase the weight every week or two.

- As a Finisher: 2 sets of "as many reps as possible" with a moderate weight, focusing on perfect form until you literally can't crunch another inch.

The Spine Health Question

Some physical therapists aren't fans of seated crunch machines because they put the spine into "loaded flexion." Basically, you're bending your back while under pressure. If you have a history of herniated discs or chronic lower back pain, you should be careful.

However, for a healthy trainee, loaded flexion is not inherently "dangerous." Our spines are meant to bend. The key is to avoid "shear" force. As long as your back is supported by the machine’s padding and you aren't jerking the weight, the risk is minimal. In fact, strengthening the abs in this range can actually help protect the back in the long run by building a stronger "shield" around your midsection.

Always listen to your body. If you feel a sharp pinch or any radiating pain in your legs, stop. Switch to an isometric exercise like a Dead Bug or a Plank. But if it just feels like your abs are being set on fire? You're doing just fine.

✨ Don't miss: That Weird Feeling in Knee No Pain: What Your Body Is Actually Trying to Tell You

Summary of Actionable Steps

If you're ready to actually see progress with the seated abdominal crunch machine, stop treated it like an afterthought. It's a powerhouse if you treat it with respect.

First, take the time to adjust the seat. Most people just sit down and go. You want the pivot point of the machine to be roughly at the level of your lower ribs. If the seat is too high or too low, the arc of the machine won't match the arc of your spine.

Second, check your ego. Just because you can move the whole stack doesn't mean you should. Drop the weight by 30% and focus on the mind-muscle connection. If you can't hold the contraction at the bottom for a full second, it's too heavy.

Lastly, track your sets. Write down the weight and reps. Treat it like a Bench Press. When you see those numbers go up over months, you’ll see the physical changes in your midsection to match.

The machine isn't a "cheat code," and it won't give you abs if your diet is a mess. But as a tool for building thick, visible abdominal blocks? It's hard to beat. Next time you're in the gym, don't walk past it. Sit down, lock your back in, and actually use the thing properly. You'll feel the difference by the third rep.

Next Steps for Your Training:

- Verify your machine's pivot point alignment before your next set.

- Implement a 3-second eccentric (lowering) phase to maximize time under tension.

- Pair this with a "bottom-up" movement like lying leg raises to ensure you're hitting the entire abdominal wall.

- Increase the resistance by the smallest possible increment once you can comfortably complete 15 perfect reps.