Ray Wylie Hubbard didn't mean to write an anthem. He was just freezing his tail off in a New Mexico winter, hiding out in a cabin, and thinking about a guy he’d seen in a bar. That’s how Up Against the Wall Redneck Mother started. It wasn't a corporate product. It wasn't a "planned" hit. It was a joke that accidentally became the definitive middle finger of the 1970s Progressive Country movement. If you've ever been to a Texas dive bar on a Saturday night, you've heard it. You've probably yelled the spelling bee part at the top of your lungs.

It's a weird song. It’s mean, it’s funny, and it’s deeply observational. But more than that, it’s a time capsule of a specific moment in Austin, Texas, when the hippies and the cowboys stopped punching each other and started sharing the same jug of whiskey.

The Night in Red River That Changed Everything

Hubbard was playing music in Red River, New Mexico, around 1973. It was a ski town, but it was also a rough-and-tumble spot for folks who didn't fit in elsewhere. He saw this guy. A real piece of work. This guy was wearing a "macho" belt buckle, probably a bit too much denim, and was generally making life miserable for everyone in the room. Hubbard started wondering what kind of mother would produce a person like that. He sat down and wrote the lyrics as a satire.

He thought it was a throwaway. Honestly, he didn't even record it first.

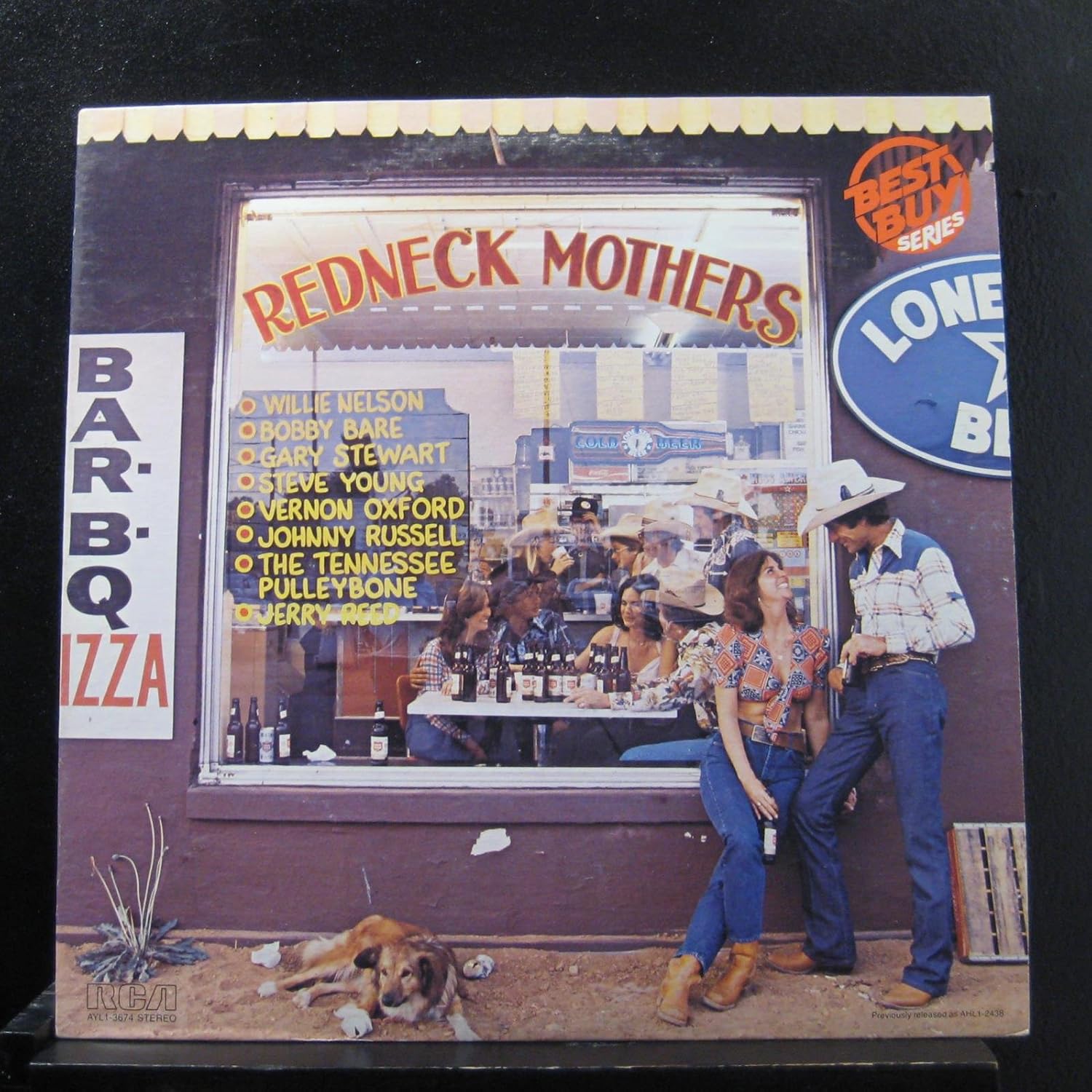

That honor went to Jerry Jeff Walker. Jerry Jeff was the wild man of the scene, the guy who recorded Viva Terlingua in a lost-to-time dancehall in Luckenbach. When Jerry Jeff put Up Against the Wall Redneck Mother on that 1973 live-feeling album, the song exploded. It became the "Born to Be Wild" for people who drove beat-up trucks and liked their beer room temperature.

Why the Satire Was Often Missed

The irony is that a lot of people the song was making fun of ended up loving it the most. Hubbard’s lyrics describe a protagonist who is "thirty-four and drinking in a honky-tonk," someone whose mother "taught him how to cuss" and "raised him up a rebel." It was a caricature of the reactionary, hyper-masculine "redneck" archetype that was prevalent during the Vietnam War era.

But here’s the thing about Texas music: if the beat is right and the chorus is catchy, people will adopt it as their own. The song became a badge of honor. It wasn't just a parody anymore. It was a lifestyle. It’s sort of like how "Born in the U.S.A." gets played at political rallies by people who don't realize it's a song about a struggling veteran. Hubbard watched his biting satire turn into a frat-house singalong. He’s been pretty vocal about the weirdness of that transition over the years. He’s a songwriter’s songwriter—the kind of guy who cites Dante and uses words like "hypnagogic"—so seeing a song about a "macho" redneck become his most famous work is a bit of a cosmic joke.

👉 See also: Is Heroes and Villains Legit? What You Need to Know Before Buying

The Anatomy of an Outlaw Classic

What makes it stick? It’s the structure. The song doesn't follow the slick Nashville formula of the early 70s. It’s loose. It’s ragged.

The famous "spelling" section is the hook that won’t quit.

- R is for "Redneck"

- E is for "Ethyl" (the gas he used to drink?)

- D is for "Don't give a damn"

It’s ridiculous. It’s pure vaudeville. But in the context of the 1970s "Cosmic Cowboy" scene, it was revolutionary. At the time, Nashville was producing "Countrypolitan" music—lots of strings, very polished, very safe. Then you had these guys in Austin like Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, and Hubbard who were playing loud, distorted guitars and singing about things that weren't exactly radio-friendly.

Up Against the Wall Redneck Mother gave that movement a voice. It was the antithesis of the Grand Ole Opry. It was messy.

The Hubbard vs. Walker Dynamic

While Jerry Jeff Walker made the song famous, Ray Wylie Hubbard is the one who had to live with it. For years, Hubbard struggled with the "Redneck Mother" legacy. He wanted to be taken seriously as a bluesman and a poet. If you listen to his later stuff, like "Snake Farm" or "Tell the Devil I’m Gettin’ There as Fast as I Can," you hear a guy who is deeply into the grit and the grease of American roots music.

But he couldn't escape the mother.

✨ Don't miss: Jack Blocker American Idol Journey: What Most People Get Wrong

Eventually, he leaned into it. He realized that the song provided him with a "pension," so to speak. It gave him the freedom to eventually make the records he actually wanted to make. It’s a classic artist’s dilemma: do you hate the hit that pays your rent but traps you in a box? Hubbard eventually found peace with it, often introducing it with a wry smile and a story that changes slightly every time he tells it.

Impact on the Texas Music Identity

You can't talk about modern Texas Country or Americana without acknowledging this track. It paved the way for the "irreverent" side of the genre. Without this song, do we get Robert Earl Keen’s "The Road Goes on Forever"? Maybe not. Do we get the humorous, self-deprecating lyrics of Todd Snider? Unlikely.

It broke the "reverence" of country music.

Before this, country songs about mothers were usually sentimental. Think about Merle Haggard’s "Mama Tried." It’s a song about a mother who tried her best but her son went to prison anyway. It’s respectful. It’s sad. Then Hubbard comes along and writes about a mother who "taught him how to cuss" and is basically responsible for him being a hell-raiser. It flipped the "Mama" trope on its head.

The Armadillo World Headquarters Era

To understand the song, you have to understand the venue. The Armadillo World Headquarters in Austin was the ground zero for this sound. You’d have a long-haired hippie with a joint in one hand and a guy with a cowboy hat and a Pearl beer in the other. They were united by their hatred of the "establishment" and their love of music that felt real.

Up Against the Wall Redneck Mother was the anthem of the Armadillo. It was the bridge. It was loud enough for the rockers and "country" enough for the traditionalists. It was a social experiment set to three chords.

🔗 Read more: Why American Beauty by the Grateful Dead is Still the Gold Standard of Americana

Myths and Misconceptions

People often think the song is a celebration of the "redneck" lifestyle. If you actually read the lyrics, it’s a pretty scathing look at a guy who is stuck in a cycle of ignorance and barroom brawls.

- Misconception 1: It was written by Jerry Jeff Walker. (Nope, Ray Wylie Hubbard wrote it.)

- Misconception 2: It’s a pro-Redneck song. (It’s a satire of a specific type of belligerent character.)

- Misconception 3: It was a radio hit. (It was an underground hit that spread through live shows and word of mouth.)

The song’s longevity is actually a bit of a miracle. It doesn't have a traditional chorus-verse-chorus structure that radio programmers love. It’s conversational. It feels like someone telling you a story over a drink. That’s the "human" element that AI can’t really replicate—that specific, jagged edge of 1970s Texas grit.

What You Should Do Next

If you want to actually understand why this matters, don't just read about it. You need to hear the evolution.

- Listen to the Jerry Jeff Walker version from Viva Terlingua. Notice the crowd noise. Notice how the room seems to lift off the ground when the chorus hits. That's the energy of a moment in time that won't happen again.

- Find a live version by Ray Wylie Hubbard from the last ten years. He plays it with a greasy, bluesy shuffle now. It’s slower, meaner, and way cooler. It shows how a songwriter can reclaim their work after forty years.

- Check out the lyrics to "Snake Farm" afterward. It’ll give you a better idea of who Hubbard is today—a master of the "grit n' groove" who is way more complex than his most famous song suggests.

- Dig into the "Cosmic Cowboy" history. Read about the Armadillo World Headquarters. Understanding the geography of Austin in 1973 helps explain why a song like this was even possible.

The song isn't just a relic. It’s a reminder that sometimes the most enduring art is the stuff we create when we aren't trying to be "important." Hubbard was just trying to make his friends laugh in a cold cabin. Instead, he wrote a song that will probably be played in Texas icehouses long after we're all gone. It’s loud, it’s obnoxious, and it’s perfectly human.

Actionable Insight: When exploring Outlaw Country, always look for the songwriter behind the performer. The "Austin Sound" was built on the backs of writers like Hubbard, Guy Clark, and Townes Van Zandt, whose stories often got overshadowed by the larger-than-life personas of the people who covered them. To truly appreciate the genre, start with the pens, not just the hats.