Most movies from the late sixties feel like museum pieces. They’re gorgeous, sure, but you can smell the mothballs on the costumes and hear the stagey stiffness in the dialogue. Then there’s Two for the Road 1967. If you haven't seen it lately, or ever, it's a total shock to the system. It doesn’t behave. It refuses to sit still. Stanley Donen, the guy who gave us Singin’ in the Rain, decided to take Audrey Hepburn and Albert Finney, throw them into a white Mercedes-Benz 230SL, and fracture time itself.

It’s a movie about a marriage. Or rather, it’s a movie about the layers of a marriage, stacked on top of each other like a messy pile of photographs. You aren't just watching a story unfold; you’re watching twelve years of resentment, lust, boredom, and genuine friendship collide in real-time.

The Non-Linear Magic of Two for the Road 1967

The structure is what usually trips people up at first, but honestly, it’s the most honest thing about the film. Life doesn't feel like a straight line when you're with someone for a decade. You look at your partner across a dinner table and you don't just see the person they are now. You see the person they were when you met them in a rainy hitchhiking spot in northern France. You see the version of them that screamed at you in a hotel room five years ago.

Frederic Raphael, who wrote the screenplay, understood this perfectly. He didn't write a "beginning, middle, and end" story. He wrote a "then and now" story that jumps across five different road trips taken by Joanna (Hepburn) and Mark (Finney).

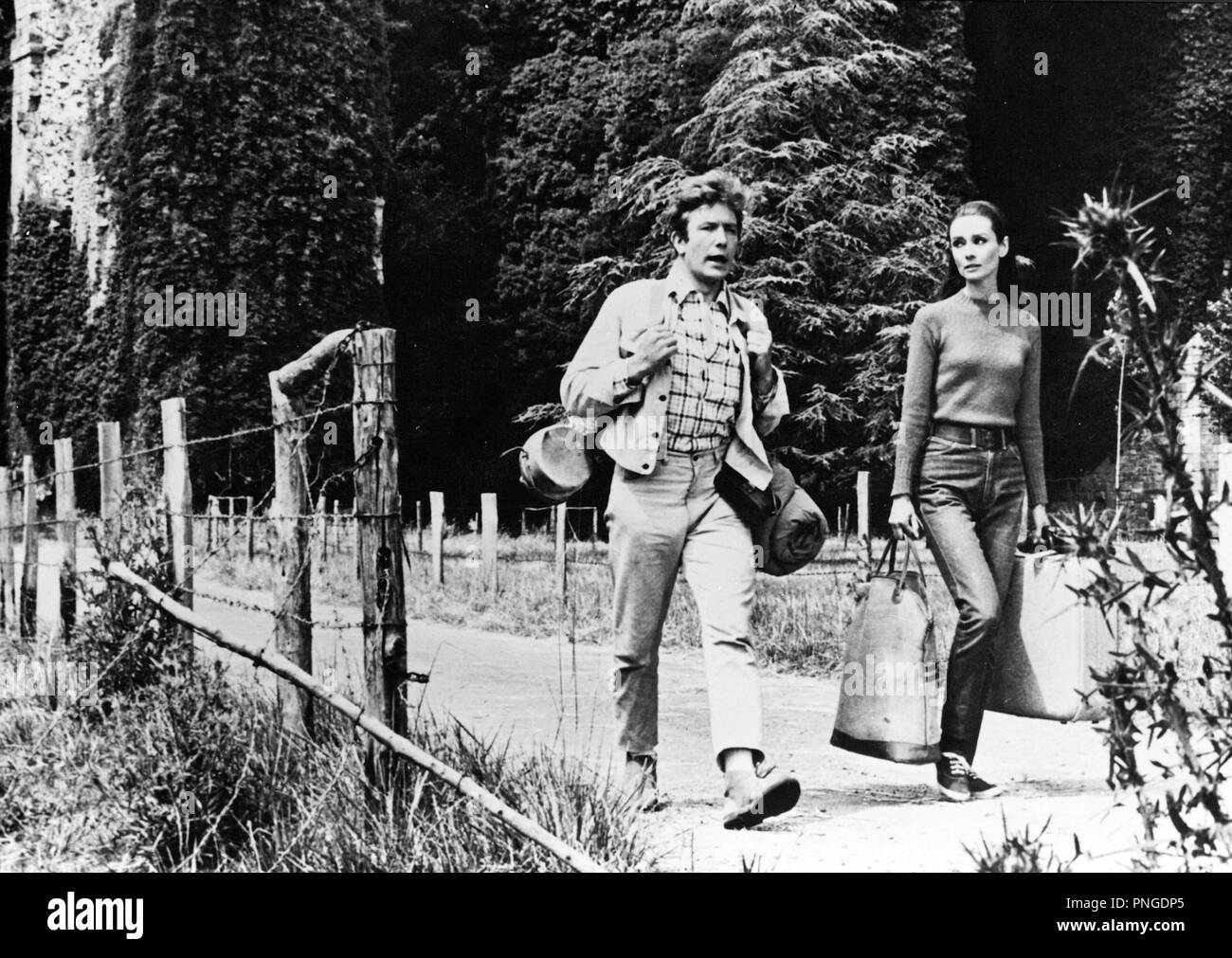

One second they’re broke students hitchhiking with nothing but a bag and a bad attitude. Suddenly, the camera cuts—maybe just by following the movement of a passing car—and they’re wealthy, bitter, and trapped in a luxury vehicle. It’s jarring. It’s meant to be. The transitions are famous among film nerds for a reason. Donen uses "match cuts" that aren't just technical tricks; they’re emotional bridges. A door closes in one year and opens in another. A question asked in 1954 is answered by a sarcastic remark in 1966.

Audrey Hepburn Like You've Never Seen Her

We’re used to Audrey Hepburn being a pixie-cut princess. We think of Roman Holiday or the iconic, slightly sanitized elegance of Breakfast at Tiffany’s. But in Two for the Road 1967, she’s different. She’s sharper. She’s occasionally mean. She’s deeply tired.

This was a pivot for her. Working with Albert Finney—who was the "angry young man" of British cinema at the time—brought out a grit in her performance that hadn't been there before. Finney plays Mark Wallace as a bit of a self-centered jerk, an architect who is more obsessed with his career than his wife’s happiness. Joanna doesn't just take it. She hits back.

📖 Related: Why Grand Funk’s Bad Time is Secretly the Best Pop Song of the 1970s

Their chemistry is legendary, and not just because of the rumors that flew around during production. They look like they’ve actually slept in those cars. They look like they know exactly which buttons to push to make the other person explode. It’s a masterclass in screen acting because it avoids the melodrama of "Old Hollywood." There are no grand speeches. Just the kind of biting, low-level bickering that defines most long-term relationships.

That Incredible 1960s Aesthetic (and the Cars)

You can't talk about this movie without talking about the clothes and the cars. It is a visual feast. But even the fashion serves the story.

In the early years, Joanna is wearing simple sweaters and messy hair. As they get richer, she transitions into high-fashion pieces by Mary Quant, Paco Rabanne, and Ken Scott. She becomes a mannequin for their success, while Mark stays largely the same, just grumpier. The car is the most consistent character. Whether it's a struggling MG TD or that sleek Mercedes, the vehicle acts as a pressure cooker.

Think about it. There’s no escape in a car. You're trapped in a metal box with your choices.

The filming took place across the south of France—the Côte d'Azur, Saint-Tropez, and the rural roads in between. It looks effortless, but the lighting and the way Donen uses the widescreen frame are incredibly deliberate. He’s showing us the vastness of the world outside the car versus the claustrophobia inside their marriage.

Why the Critics Were Split

When it first came out, not everyone "got" it. Some critics found the jumping back and forth confusing. They wanted a traditional romance. They wanted Audrey Hepburn to be a darling, not a woman considering an affair because her husband is a bore.

👉 See also: Why La Mera Mera Radio is Actually Dominating Local Airwaves Right Now

But over time, the film’s reputation has skyrocketed. It’s now seen as a precursor to modern "relationship" movies like Blue Valentine or the Before trilogy. It deals with things that were taboo for a "star vehicle" in 1967:

- The crushing weight of domesticity.

- How children can sometimes drive a wedge between couples rather than bring them together.

- The reality that you can love someone and still not particularly like them on a Tuesday afternoon.

- The way memory distorts the "good old days."

Henry Mancini’s Secret Weapon

The score. If you strip away the visuals, the music by Henry Mancini tells the whole story. Mancini himself often said this was his favorite score he ever wrote.

The main theme is bittersweet. It’s not a triumphal love song. It’s got a wandering, slightly lonely quality to it. It follows the road. When the couple is young and hopeful, the arrangement is light. When they’re older and cynical, the music feels heavier, more melancholic. It’s the glue that holds the frantic editing together. Without Mancini’s strings, the movie might have felt like a chaotic mess. With them, it feels like a poem.

Real Talk: The "Manchester" Scene

There’s a specific sequence involving an American couple, the Meachams, and their incredibly spoiled daughter. It’s one of the few times the movie leans into broad comedy, and some people think it dates the film. Honestly? It’s a necessary break.

The Meachams represent the "worst-case scenario" for Mark and Joanna. They are the warning sign on the side of the road. Watching Mark and Joanna navigate the nightmare of a "perfect" family trip adds a layer of dread to their own future. It’s funny, but it’s also a horror movie for anyone who values their independence.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Ending

People often debate whether Two for the Road 1967 has a happy ending. On the surface, they’re still together. They’re crossing a border. They’re still sniping at each other, but they’re in the same car.

✨ Don't miss: Why Love Island Season 7 Episode 23 Still Feels Like a Fever Dream

Is that a win?

The film suggests that "happily ever after" is a lie. Instead, it offers "still going." In a world where every romance movie ends at the wedding, this movie starts long after the honeymoon and asks: How do you keep driving when you know the road is full of potholes? The ending isn't about a resolution of their problems. Mark is still arrogant. Joanna is still restless. But they have a shared language. They have those twelve years of road maps. In the final scene, they’re still "two for the road," and maybe that’s the best anyone can hope for.

Actionable Takeaways for Film Lovers

If you're going to dive into this classic, or re-watch it, here’s how to get the most out of the experience:

- Watch the Wardrobe: Don’t just look at the clothes because they’re pretty. Notice how Joanna’s outfits get more structured and "armored" as the marriage gets more difficult. The Paco Rabanne "metal" dress is the ultimate symbol of her putting up a barrier.

- Track the Transitions: Pay attention to how Donen moves between eras. Sometimes it’s a sound, sometimes it’s a color, and sometimes it’s a literal turn of the steering wheel. It’s a masterclass in editing.

- Listen to the Silence: Some of the most powerful moments aren't the witty barbs. It's the moments where they have nothing left to say to each other.

- Contextualize the Era: Remember that in 1967, the "Studio System" was dying and the "New Hollywood" was being born. This film is the perfect bridge between the two—it has the gloss of a big-budget production but the soul of an experimental European art film.

Two for the Road 1967 isn't just a movie for people who like old cars or Audrey Hepburn. It's a movie for anyone who has ever been in a long relationship and wondered where the time went. It’s messy, it’s beautiful, and it’s remarkably honest about the fact that love isn't a destination—it's just a very long, very complicated drive through the countryside.

If you want to understand modern cinema, you have to understand how Donen broke the rules here. He took the most famous woman in the world and put her in a story that wasn't afraid to be ugly. That’s why we’re still talking about it sixty years later.

Next Steps for the Cinephile:

Check out the 4K restoration if you can find it; the French landscapes deserve the extra pixels. After that, watch Charade (1963) to see the same director and actress working in a totally different genre, then move on to The Last Five Years to see how modern directors are still trying to figure out the non-linear relationship story that Two for the Road 1967 perfected decades ago.