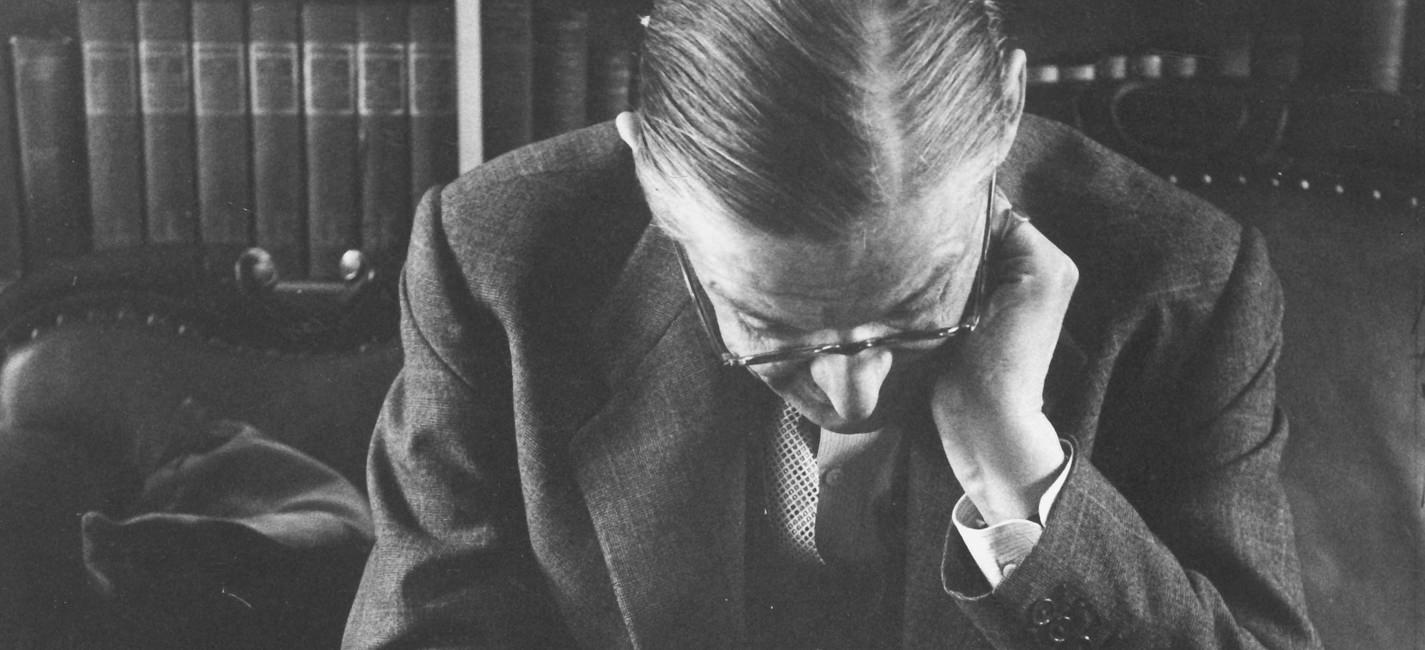

T.S. Eliot was a mess. Well, maybe not a mess in the way we think of it now—he wasn’t posting cryptic stories on Instagram at 3:00 AM—but his internal life during the late 1930s was basically a high-speed collision of spiritual crisis and global dread. He’d already written "The Waste Land," which made him the poster boy for modern disillusionment, but he wasn’t done. He felt like he hadn’t quite finished the thought. That’s how we got the Four Quartets.

It’s a weird piece of work. It’s a poem, sure. But it’s also a philosophical argument, a prayer, and a bit of a historical ghost story. Honestly, if you try to read it like a standard narrative, you’ll probably want to chuck the book across the room within five minutes. It’s dense. It’s repetitive. It loops back on itself like a glitching record. But that’s exactly why people are still obsessed with it.

The Burnt Norton Breakthrough

In 1934, Eliot visited an abandoned manor house in Gloucestershire called Burnt Norton. He wasn't there to write a masterpiece; he was just wandering around. But something about the empty pools and the formal rose garden triggered a massive meditation on "what might have been." We’ve all been there. You think about that one person you didn't date or the job you didn't take. Eliot takes that universal "fomo" and turns it into a metaphysical inquiry.

He starts talking about time. Not clock time, but the weird way that the past and the future are kind of always living inside the present moment.

"Time present and time past / Are both perhaps present in time future"

He’s basically saying that everything we’ve ever done and everything we might do is stacked on top of each other right now. It’s heavy stuff. This first quartet, Burnt Norton, sets the stage for the rest of the cycle. It introduces the "still point of the turning world." Imagine a spinning top. The very center isn't moving, even though the edges are a blur. For Eliot, finding that still point was the only way to survive the chaos of the 20th century.

💡 You might also like: Why the Blue Jordan 13 Retro Still Dominates the Streets

World War II and the London Blitz

By the time he was working on the later poems—East Coker, The Dry Salvages, and Little Gidding—the world was literally on fire. Eliot was a fire warden in London during the Blitz. He spent nights on rooftops watching German bombers drop incendiaries on the city. You can feel that heat in the text.

Little Gidding, the final poem, is haunted by this. He describes a "dark dove with the flickering tongue" descending. That’s not a literal bird; it’s a Spitfire or a Messerschmitt. It’s a terrifying image of destruction that he somehow weaves into a spiritual purification. He’s trying to figure out if all this suffering actually means something or if we’re all just meat in a grinder.

He goes back to his roots, too. East Coker is the name of the village in Somerset where his ancestors lived before moving to America. He’s looking for a beginning to match his end. "In my beginning is my end," he writes. Then he flips it at the very end of the poem: "In my end is my beginning." It’s a bit of a mind-bender, but it's basically his way of saying that life is cyclical, not linear.

Why the "Quartet" Structure Matters

Eliot was a huge fan of Beethoven. Specifically, the late string quartets. He wanted to do with words what Beethoven did with four instruments.

- Five movements per poem.

- A "musical" return of themes.

- Contrasting voices (sometimes he sounds like a dry academic, sometimes like a weeping mystic).

- A focus on harmony emerging from discord.

He wasn't just being a snob. He genuinely believed that poetry could reach a level of "incantation" where the meaning matters less than the feeling it evokes in your gut. It’s like listening to a song in a language you don’t speak but still knowing exactly what it’s about.

📖 Related: Sleeping With Your Neighbor: Why It Is More Complicated Than You Think

The Complexity of Faith

Let’s be real: Eliot’s conversion to Anglo-Catholicism in 1927 annoyed a lot of his cool, secular friends. They thought he’d sold out. They wanted more of the "hollow men" and less of the "kneeling where prayer has been valid."

But the Four Quartets isn't a simple "yay, Jesus" kind of poem. It’s full of doubt. It’s full of "the middle way," which he describes as a path where there is no path. He talks about the "frigid purgatorial fires." It’s a tough, demanding faith. He’s not promising anyone a happy ending. He’s promising a "costing not less than everything."

That’s why even atheists tend to respect this poem. It doesn't ignore the darkness; it stares right into it. It acknowledges that being human is mostly about failing and trying again. "For us, there is only the trying. The rest is not our business." That’s a pretty liberating thought if you really sit with it. You don't have to win. You just have to try.

The Problem with Eliot

We can't talk about the Four Quartets without acknowledging that T.S. Eliot was a complicated, often problematic guy. His earlier work has some pretty gross antisemitic tropes. By the time he wrote the Quartets, he was leaning into a very specific, traditionalist European worldview that can feel exclusionary.

Scholars like Anthony Julius have written extensively about this. You have to decide if you can separate the art from the artist. Most people find that the Quartets transcend Eliot’s personal failings because they deal with such universal themes—time, death, and the hope for some kind of cosmic order.

👉 See also: At Home French Manicure: Why Yours Looks Cheap and How to Fix It

What You Get Wrong About the Ending

The very last lines are some of the most famous in English literature.

"And all shall be well and / All manner of thing shall be well / When the tongues of flame are in-folded / Into the crowned knot of fire / And the fire and the rose are one."

People think this is a fluffy, optimistic ending. It’s not. He’s quoting Julian of Norwich, a 14th-century mystic who saw some horrific things. The "fire" and the "rose" becoming one is a massive, painful synthesis. It’s the idea that the things that hurt us and the things that give us beauty are actually the same thing when viewed from a high enough perspective. It’s a hard-won peace.

How to Actually Read It

Don’t try to understand every reference. You’ll go crazy. Eliot references Dante, the Bhagavad Gita, Heraclitus, and St. John of the Cross. Unless you have a PhD in Comparative Literature, you’re going to miss stuff.

Here is the secret: Read it out loud. Seriously. The rhythm is where the magic is.

- Listen for the pauses. Eliot uses a lot of "caesuras"—those little breaks in the middle of a line.

- Notice the geography. Each poem is tied to a specific place. Look up photos of the chapel at Little Gidding or the rocks called the Dry Salvages off the coast of Massachusetts. It grounds the abstract philosophy in real dirt and salt water.

- Accept the boredom. There are parts where he talks about the "deformation of the soul" that are, frankly, a bit of a slog. Let them wash over you. The "boring" parts make the lyrical explosions feel much more powerful.

Actionable Insights for the Modern Reader

If you’re feeling overwhelmed by the pace of modern life—the constant notifications, the sense that the world is ending every Tuesday—the Four Quartets is actually a weirdly good antidote.

- Practice the "Still Point." Take five minutes today to sit somewhere and just observe the movement around you without participating in it. That’s Eliot’s "still point." It’s a mental reset.

- Audit Your "What Might Have Beens." Identify one regret you’re carrying. Instead of trying to fix it or mourn it, try to see it as part of your "present" self, as Eliot suggests in Burnt Norton. It shaped you. It’s not a ghost; it’s a foundation.

- Read the Sources. If a particular section hits you, look up the source. Reading St. John of the Cross’s Dark Night of the Soul alongside East Coker will give you a much deeper appreciation for what Eliot was trying to do with the "theology of emptiness."

- Visit the Places. If you’re ever in England or New England, go to the sites. There is a specific kind of silence in the chapel at Little Gidding that explains the poem better than any textbook ever could.

The Four Quartets isn't just a book on a shelf. It’s a survival manual for people who think too much. It reminds us that while we’re stuck in time, we’re also part of something that doesn't care about clocks at all. And honestly, that’s a pretty comforting thought.