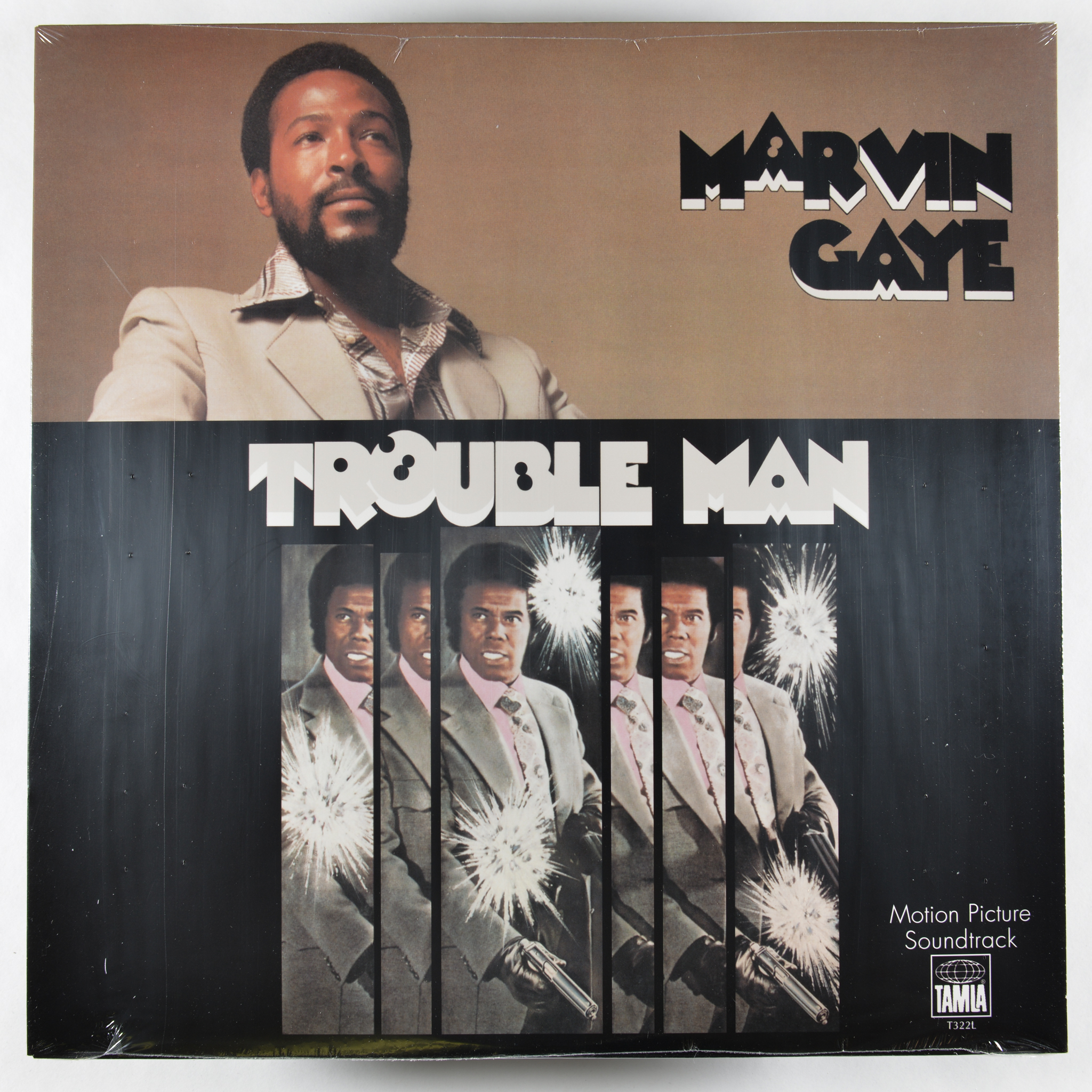

Marvin Gaye was terrified. Honestly, he was. By 1972, he had just finished What’s Going On, an album that basically redefined what a "pop" star could say about the world. He was the prince of Motown, but he was also a man who felt like he was drowning in his own success. Then came the offer to score a movie. Not just any movie, but a gritty, street-level Blaxploitation flick called Trouble Man. Most people today hear the title track and think, "Oh, that’s a cool vibe," but they don't realize that Trouble Man by Marvin Gaye was actually a desperate, brilliant attempt by an artist to prove he wasn't just a singer. He wanted to be a composer. He wanted to be Duke Ellington.

He did it.

It's weird. When you talk about the great Blaxploitation soundtracks, people always scream about Isaac Hayes and Shaft or Curtis Mayfield and Superfly. Those are incredible. No doubt. But Marvin’s approach was different. It wasn't just about "the funk." It was about the atmosphere. It was about the loneliness of a character named Mr. T. It was a jazz record disguised as a soul soundtrack.

The Risky Pivot After What’s Going On

Imagine you just released one of the greatest albums of all time. Your label, Motown, finally trusts you. You have the world at your feet. Most artists would have just made What’s Going On Pt. 2. Instead, Marvin went into a dark room and started playing the piano and the Moog synthesizer.

The movie itself? Trouble Man isn't exactly a cinematic titan. It stars Robert Hooks as a "fixer" in the inner city. It’s fine. It’s a standard 70s crime drama. But the music Gaye wrote for it is lightyears ahead of the film. He didn't just write songs; he wrote a score. He did the arrangements. He conducted. He spent hours obsessing over the way a saxophone could mirror the sound of a police siren.

He was obsessed with the idea of the "Trouble Man." He saw himself in that character. A guy who moves through the shadows, trying to do the right thing but getting his hands dirty along the way. You can hear that tension in the music. It’s jittery. It’s smooth. It’s contradictory.

Why the title track is a technical marvel

The song "Trouble Man" is the only track on the album with a full vocal performance, and it’s a masterclass in vocal layering. Marvin was a pioneer of this. He didn't just record a lead vocal; he recorded layers of himself. He’s his own backup choir.

Listen closely to the lyrics. "I come up hard / But that’s okay / ‘Cause Trouble Man / Don’t get in my way."

✨ Don't miss: Chase From Paw Patrol: Why This German Shepherd Is Actually a Big Deal

It’s a brag, sure. But his voice sounds thin and haunted at the edges. He’s singing about survival, but he sounds like he’s looking over his shoulder. The song peaks with this soaring, almost screeching saxophone that cuts through the groove. That wasn't just for show. It was meant to represent the urban chaos of Los Angeles in the early 70s.

Composition over Commercialism

If you buy the vinyl today, you'll notice something immediately: most of it is instrumental. For a superstar singer at the height of his powers, that was a huge gamble. Motown's Berry Gordy was famously skeptical of Marvin’s experimental side. He wanted hits. He wanted "I Heard It Through the Grapevine" style earners.

Instead, Marvin gave him "T Stands for Trouble."

It’s a menacing, rolling piece of music. It uses odd time signatures and jazz-fusion elements that feel more like Miles Davis than Smokey Robinson. The use of the Moog synthesizer was particularly groundbreaking. In 1972, the Moog was still a bit of a mystery to R&B producers. Marvin used it to create these low, pulsing basslines that felt like a heartbeat. It gave the album a cinematic "weight" that other soundtracks lacked.

You’ve got to remember the context. This was a time when "Black Cinema" was being pigeonholed. It was either "pimp" movies or "cop" movies. By bringing a high-art, symphonic sensibility to Trouble Man by Marvin Gaye, he was making a statement. He was saying that the Black experience in the city deserved the same complexity as a Bernard Herrmann score for a Hitchcock film.

The Recording Sessions: Perfectionism and Pain

Marvin didn't work like other people. He was a night owl. He’d roll into the studio at 2 AM with a suitcase full of ideas and stay until the sun came up. The musicians who played on these sessions—including members of the legendary Funk Brothers—have spoken about how exacting he was.

He wasn't just humming tunes. He was dictating specific horn lines. He was playing the keys himself.

🔗 Read more: Charlize Theron Sweet November: Why This Panned Rom-Com Became a Cult Favorite

There’s a specific story about the track "“T” Plays It Cool." Marvin wanted a very specific "vibe" that felt like walking down a street where you know you’re being watched. He kept making the drummer, Gene Pello, redo the snare hits because they weren't "dry" enough. He wanted it to sound like footsteps on concrete. That level of detail is why the album still sounds modern today. You can sample it—and everyone from Biggie Smalls to Kendrick Lamar has—and it doesn't sound dated. It just sounds like "cool."

Why the Critics (Initially) Didn't Get It

When the album dropped in December 1972, the reviews were mixed. Some people felt cheated. They bought a Marvin Gaye record and only got one "real" song with singing. They called it "background music."

They were wrong.

It took years for people to realize that the instrumentals were the point. Tracks like "Deep-in-it" or "Life is a Gamble" aren't fillers. They are mood pieces. They’re the precursors to what we now call "Lo-fi beats" or ambient soul. Marvin was building a world. He was using the studio as an instrument.

Honestly, if you listen to Trouble Man back-to-back with his next big record, Let’s Get It On, you can see the bridge. Trouble Man was where he mastered the art of the "groove." He learned how to let a beat breathe. He learned how to use silence.

The influence on Hip-Hop and Modern R&B

You can't talk about this album without talking about its legacy. Producers love this record. Why? Because it’s "thick." The textures are dense.

- Sample Goldmine: The drums on this record have been chopped up thousands of times.

- The "Vibe" Blueprint: Modern artists like Frank Ocean or Solange owe a massive debt to the atmospheric, non-linear structure of this soundtrack.

- Cinematic Soul: It proved that R&B artists could handle a full film score, paving the way for people like Terence Blanchard or even Quincy Jones’ later work.

What Most People Get Wrong

People think this was a "contractual obligation" album. They think Marvin did it for a paycheck while he was preparing his next masterpiece.

💡 You might also like: Charlie Charlie Are You Here: Why the Viral Demon Myth Still Creeps Us Out

That’s a myth.

Marvin Gaye actually loved this album more than What’s Going On. He kept a copy of the score in his house until the day he died. To him, this was his "serious" work. It was the proof that he was a musician, not just a "voice." When you listen to it with that in mind—knowing the artist was fighting for respect—the music takes on a whole new layer of meaning. It’s the sound of a man demanding to be taken seriously.

How to Truly Experience Trouble Man

Don't just put it on shuffle. Don't play it while you're doing the dishes. This isn't a "background" record, despite what the 1972 critics said.

- Get the right gear: If you have a pair of decent headphones, use them. The panning on the percussion is incredible.

- Watch the movie (once): It’s worth seeing the visuals just to understand how the music fits the movement on screen. It makes the "chase" themes make way more sense.

- Listen for the Moog: Pay attention to those weird, low-frequency hums. It was 1972. That was the future.

- Compare it to the 1972 "Big Three": Listen to Shaft, Superfly, and Trouble Man in a row. You'll notice that Marvin's is the most "lonely" of the three. It’s the one that feels the most personal.

The reality of Trouble Man by Marvin Gaye is that it’s a transitional fossil. It’s the missing link between the social consciousness of his early 70s work and the pure, unadulterated sensuality of his late 70s work. It’s the sound of a genius figuring out his next move. It isn't just a soundtrack. It’s a self-portrait.

If you want to understand the full scope of Marvin Gaye’s talent, you have to go beyond the hits. You have to go into the shadows of this record. It’s dark, it’s moody, and it’s arguably the most honest thing he ever recorded. It doesn't ask for your love; it just exists, cool and detached, like the man himself.

Next Steps for the Listener:

To fully appreciate the technical complexity of the album, find the Trouble Man: 40th Anniversary Expanded Edition. This release contains the original film score versions, which are often different from the album takes. Notice how Gaye stripped back the arrangements for the vinyl release to make it more "listenable," while the film cues are much more experimental and dissonant. Comparing the "Main Theme" from the film to the "Trouble Man" single reveals exactly how Gaye balanced his commercial instincts with his avant-garde ambitions.