It’s happening right now. Inside your body, trillions of times a second, a tiny molecular machine is reading a code and spitting out the physical "stuff" of you. We call it translation in biology steps, but honestly, it’s more like a high-speed 3D printing factory run by enzymes. If this process stopped for even a minute, you’d essentially dissolve.

Most people remember a blurry diagram from 10th-grade biology with some blobs labeled "ribosome." But the reality is way more chaotic and beautiful. It's the moment where the abstract information stored in your DNA becomes a physical reality—like a muscle fiber, an enzyme to digest your lunch, or the collagen keeping your skin from sagging.

The Messenger: Why DNA Doesn't Do the Work

DNA is the boss. And like most bosses, it doesn't actually get its hands dirty. It stays tucked away in the nucleus, safe and sound. To get anything done, it sends a memo. That memo is mRNA (messenger RNA).

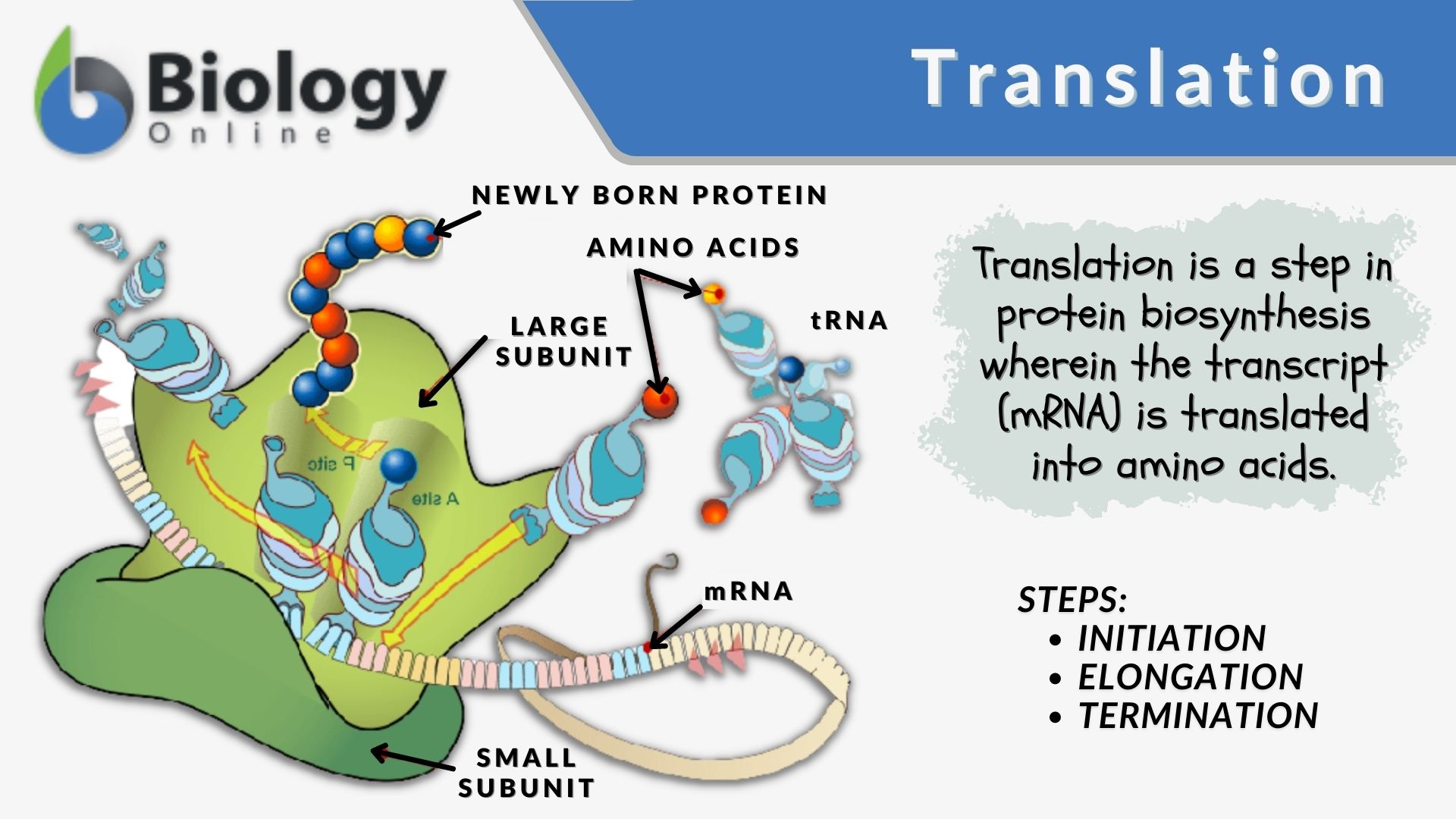

This is where the translation in biology steps truly begin. The mRNA travels out of the nucleus and into the cytoplasm, looking for a ribosome. Think of the ribosome as a giant, two-part construction site. It’s made of rRNA and proteins, and its only job is to translate the language of nucleic acids into the language of proteins.

It’s a language barrier problem. Nucleic acids speak in "nucleotides" (A, U, C, G), while proteins speak in "amino acids." You can't just stick a nucleotide onto a protein. You need a translator. That’s where tRNA comes in.

Step One: Initiation and the Search for "AUG"

Nothing starts until the ribosome finds the green light. In the world of genetics, that green light is a specific sequence: AUG.

This is the "Start Codon."

🔗 Read more: Exercises to Get Big Boobs: What Actually Works and the Anatomy Most People Ignore

The small subunit of the ribosome latches onto the mRNA and slides along it like a bead on a string. It’s searching. When it hits AUG, everything clicks into place. A special tRNA molecule, carrying an amino acid called Methionine, arrives. This is the first piece of every protein ever made in your body.

Why the "Start" Matters

If the ribosome misses the start, the whole message becomes gibberish. Imagine trying to read a sentence but skipping the first letter of every word. "The cat ran" becomes "hec atr an." In biology, we call this a "frameshift," and it's usually catastrophic. This is how some genetic diseases, like certain forms of Tay-Sachs, do their damage. They mess with the starting line or the "reading frame."

The Heavy Lifting: Elongation

Once the "Start" is established, the large ribosomal subunit clamps down on top. Now the factory is open for business.

The ribosome has three slots. Scientists, being slightly unimaginative, named them A, P, and E.

- The A Site: The "Arrival" or Aminoacyl site. This is where a new tRNA enters, carrying a fresh amino acid.

- The P Site: The "Peptidyl" site. This is where the growing protein chain sits.

- The E Site: The "Exit" site. Once a tRNA has given up its amino acid, it’s kicked out here to go find another one in the cytoplasm.

The ribosome moves along the mRNA one "codon" (a three-letter word) at a time. It’s a rhythmic, mechanical process. The tRNA acts as the bridge. On one end, it has an "anticodon" that matches the mRNA. On the other end, it carries the specific amino acid that matches that code.

It’s precise.

💡 You might also like: Products With Red 40: What Most People Get Wrong

If the mRNA says "GGU," the tRNA carrying Glycine will show up. If it says "UUA," Leucine arrives. The ribosome facilitates a peptide bond between the old amino acid and the new one. This chain gets longer and longer, poking out of the top of the ribosome like a growing tail.

The Final Act: Termination and the "Stop" Codon

How does the ribosome know when the protein is finished? It hits a wall.

There are three specific sequences—UAA, UAG, and UGA—that don't code for any amino acid. They are "Stop Codons." When the ribosome hits one of these, no tRNA can bind to it. Instead, a "release factor" protein wanders in. It basically tells the ribosome, "We’re done here."

The whole complex falls apart. The ribosome subunits separate, the mRNA is released (and often recycled), and the brand-new protein chain floats away.

It’s Not a Protein Yet

Here is a common misconception: people think the chain that leaves the ribosome is a finished protein. It’s not. It’s just a polypeptide—a long string of "beads." To become a functional protein, it has to fold.

It twists. It turns. It curls into helices or flattens into sheets. Sometimes it needs "chaperone" proteins to help it find the right shape. If it folds wrong, it’s useless—or worse, toxic. Think of Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s; these are essentially "misfolding" crises where the translation in biology steps worked fine, but the post-game cleanup failed.

📖 Related: Why Sometimes You Just Need a Hug: The Real Science of Physical Touch

The Speed and Scale of Life

You might think this sounds slow. It’s actually terrifyingly fast. In bacteria like E. coli, ribosomes can add about 20 amino acids per second. In humans, it’s a bit slower but still incredible.

Multiple ribosomes usually read the same mRNA at the same time. This creates a "polyribosome." It looks like a string of pearls, with each pearl being a ribosome pumping out a copy of the same protein. This allows your cells to flood the system with a specific enzyme the moment it’s needed.

The "Mistakes" We Actually Need

Biology isn't perfect, and that’s a good thing. Sometimes, the ribosome makes a mistake. This is one source of "translational noise." While most mistakes are bad, some are actually regulated.

Take "Stop Codon Readthrough." Sometimes a cell wants the ribosome to ignore the stop sign and keep going to create a longer, different version of a protein. This is common in viruses and even some of our own neural tissues. It’s a way of getting two different tools out of the same blueprint.

Actionable Insights for Biology Students and Enthusiasts

Understanding the translation in biology steps isn't just about passing a test; it's about understanding how life builds itself. If you're trying to master this for a course or just personal knowledge, don't just memorize the names. Map the logic.

- Visualize the "A-P-E" sites as a conveyor belt. Use the mnemonic: Arrival, Processing, Exit. It simplifies the movement of tRNA significantly.

- Focus on the "Reading Frame." Understand that the most dangerous mutations aren't just "wrong letters," but "extra or missing letters" that shift the entire sequence.

- Connect it to medicine. Many antibiotics, like Tetracycline or Erythromycin, work by specifically gumming up bacterial ribosomes while leaving human ones alone. When you take an antibiotic, you are literally pausing translation in the "bad guys."

- Check the folding. Remember that a protein's function is determined by its 3D shape, which is the direct result of the sequence created during translation.

To truly see this in action, look for real-time molecular animations of "Kinesin" or "Ribosome translocation." Seeing the mechanical "walking" of these molecules makes the chemistry feel much more like the engineering feat it truly is.