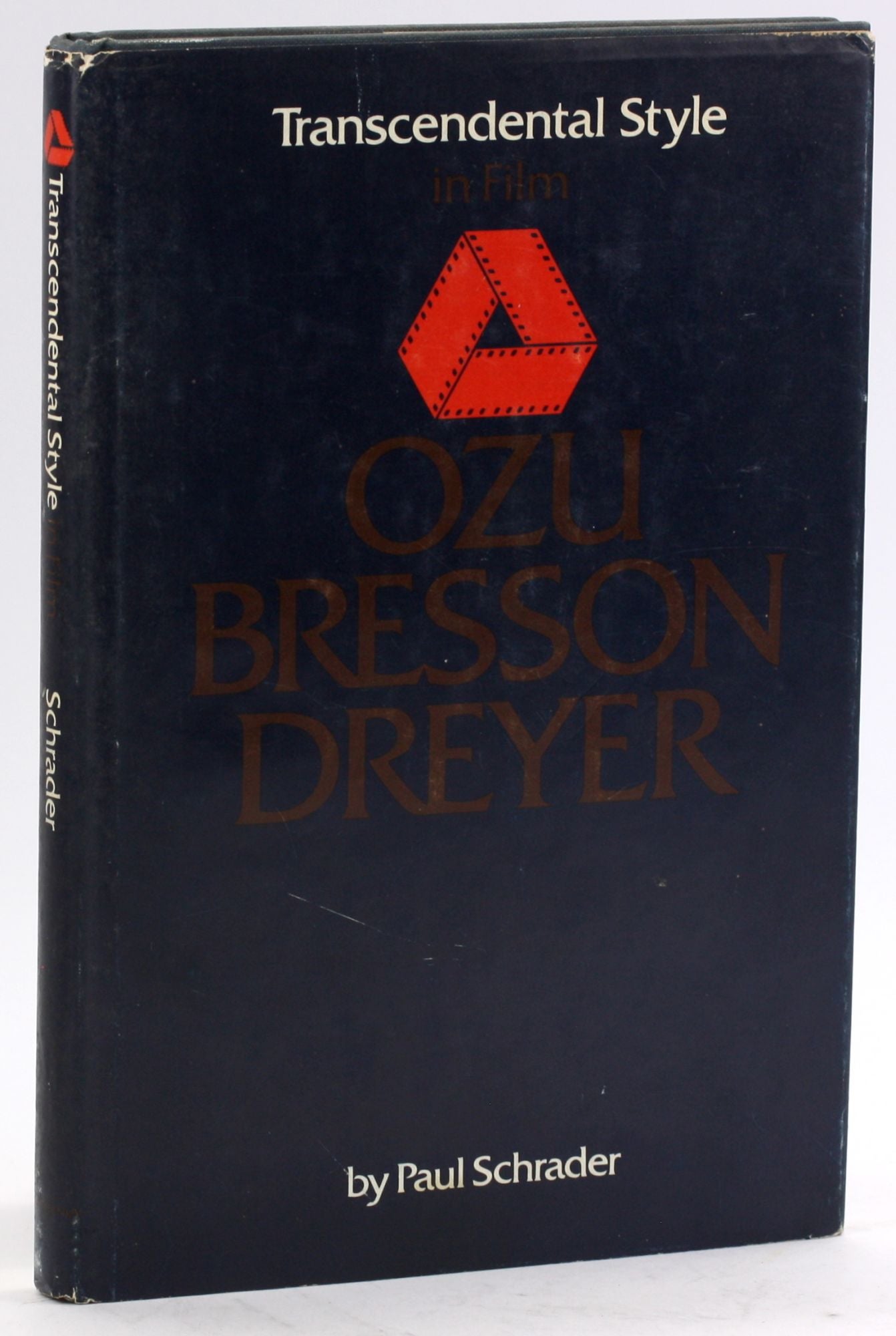

You’ve probably seen a movie that felt more like a prayer than a piece of entertainment. No explosions. No witty banter. Just a long, unblinking shot of a tea kettle or a man staring at a stone wall. Most people turn these off after ten minutes because they're "boring." But for a specific subset of film nerds, these moments are the peak of the medium. We're talking about transcendental style in film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer. It’s a term coined by Paul Schrader back in 1972, long before he wrote Taxi Driver or directed First Reformed. He wanted to figure out how movies could capture the "holy" without relying on cheap special effects or glowing halos.

It's not about religion, exactly. It's about a specific way of looking at the world that forces the viewer to slow down until they see something beyond the surface.

The Man Who Defined the Void: Paul Schrader

Schrader was raised in a strict Calvinist household where movies were basically forbidden fruit. When he finally started watching them, he didn't look for escapism. He looked for the spirit. In his seminal book, Transcendental Style in Film, he argued that Yasujirō Ozu, Robert Bresson, and Carl Theodor Dreyer were all doing the same thing, despite coming from totally different cultures.

They weren't trying to entertain you. Honestly, they were trying to exhaust you. By using "stasis" and "withholding," they strip away the distractions of plot until you're forced to confront the silence. It’s a "limit-set" of cinema.

Yasujirō Ozu and the Art of the Tea Kettle

If you watch Tokyo Story or Late Spring, you'll notice something weird. The camera never moves. It sits about three feet off the floor—the height of a person sitting on a tatami mat. This is the "tatami shot." Ozu didn't care about Hollywood's 180-degree rule. He’d jump across the line of action whenever he felt like it because he wasn't interested in making a seamless "reality." He wanted a formal, geometric space.

💡 You might also like: Ebonie Smith Movies and TV Shows: The Child Star Who Actually Made It Out Okay

Then there are the "pillow shots." These are random cutaways to a landscape, a train station, or just a vase in a room. They don't move the story forward. They are moments of Zen. You’re watching a daughter talk to her father about marriage, and suddenly—BAM—here’s a shot of a mountain for ten seconds. It forces a pause. It acknowledges that the world exists outside of the characters' tiny dramas.

Ozu uses "the everyday" to reach the "sacred." By focusing on the mundane chores of a Japanese family, he hits on something universal. You realize that the repetitive nature of life—the drinking of tea, the folding of clothes—is where the real weight of existence lives. It’s quiet. It’s devastating.

Robert Bresson: The Director Who Hated "Actors"

Bresson is the hardest one for modern audiences to swallow. He famously refused to use professional actors. He called them "models." He would make his models repeat a single line of dialogue fifty times until all the emotion was sucked out of it. He didn't want "performance." He wanted the pure essence of a human being.

In Pickpocket or A Man Escaped, the characters have stone-cold faces. They don't cry when they're sad. They don't scream when they're in pain. This is what Bresson called "the path of the ear to the heart." By removing the obvious emotion, he makes you do the work. If a character is crying, you just watch them cry. If a character is expressionless, you have to project your own soul into that void.

📖 Related: Eazy-E: The Business Genius and Street Legend Most People Get Wrong

Bresson was obsessed with hands. Close-ups of hands opening doors, counting money, or touching bars. To him, the physical world was a prison, and the "transcendental" was the moment of grace that breaks through that prison. It’s spiritual minimalism. He uses sound—the clinking of spoons, the shuffling of feet—to ground you in a harsh reality before he finally lets the "light" in during the final frame.

Carl Theodor Dreyer and the Face of God

Dreyer is the bridge. While Ozu is about the environment and Bresson is about the action, Dreyer is about the face. The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928) is basically 80 minutes of extreme close-ups. You see every pore, every tear, every twitch of Renée Jeanne Falconetti’s skin.

It’s suffocating.

But that’s the point. Dreyer used the camera like a microscope to find the soul. In his later film, Ordet, he takes a slow, methodical approach to a story about a family on a farm. The pacing is glacial. Characters speak with long pauses between every sentence. Then, at the very end, something "impossible" happens—a miracle. Because the rest of the movie was so grounded and "boring," that miracle feels earned. It feels real.

👉 See also: Drunk on You Lyrics: What Luke Bryan Fans Still Get Wrong

Why Do We Still Care?

You might think this is all just dusty film school stuff. It’s not. Look at modern cinema. You can see Ozu’s DNA in the films of Hirokazu Kore-eda (Shoplifters). You can see Bresson’s DNA in the works of the Dardenne brothers or even Wes Anderson (though Wes uses it for comedy). Paul Schrader himself updated his theories in 2018, looking at "Slow Cinema" directors like Apichatpong Weerasethakul or Béla Tarr.

The world is loud now. Our phones ping every six seconds. Our movies are edited so fast they give you a headache. Transcendental style in film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer offers an alternative. It’s a way to reclaim your attention. It’s a way to realize that silence isn't "nothing."

There's a common misconception that these films are "sad." Actually, they're often quite peaceful. They accept that life is full of loss and that the "absolute" is something we can only glimpse in the cracks of the everyday.

Actionable Steps for the Aspiring Cinephile

If you want to actually "get" these movies instead of just reading about them, you have to change how you watch.

- Put the phone in another room. This isn't a "second screen" experience. If you look away for ten seconds, you lose the rhythm.

- Start with Ozu's Good Morning. It's actually a comedy about kids who go on a silence strike because they want a TV. It’s a "gateway drug" to his more serious stuff like Tokyo Story.

- Watch Bresson's Au Hasard Balthazar. It’s about a donkey. Yes, a donkey. It follows the donkey through different owners, and by the end, you will likely be weeping. It’s the best example of how Bresson uses a "model" (in this case, an animal that can't "act") to reflect human cruelty and grace.

- Don't fight the boredom. When you feel yourself getting restless, ask why. Usually, it’s because the movie is refusing to give you what you want (drama, resolution, speed). Lean into that frustration. That’s where the "transcendental" starts.

- Look for the "Disparity." Schrader says these films have three parts: the Everyday (the boring stuff), the Disparity (a growing sense that something is wrong or missing), and the Stasis (the final frozen image that resolves the tension). Try to identify these stages as you watch.

Transcendental style isn't a genre. It's a strategy. It's a way of using a camera to do something that cameras aren't supposed to do: capture the invisible. Whether you're a believer or an atheist, there is something undeniably powerful about a filmmaker who trusts you enough to stay quiet.

Go watch Ordet. Watch the final ten minutes. Don't look away. You’ll see what everyone is talking about.