Harper Lee didn't want pictures. When To Kill a Mockingbird first hit shelves in 1960, the cover was a simple, evocative design by Shirley Smith featuring a gnarled tree and a single amber leaf. It was moody. It was sparse. But as the book transformed from a surprise bestseller into a global cultural juggernaut, the world started demanding a way to see Maycomb. We wanted to see the knot in the oak tree. We wanted to see the porch where Boo Radley sat. This hunger for To Kill a Mockingbird drawings isn’t just about fan art; it’s about how we visualize justice, childhood, and the ghosts of the American South.

Honestly, it’s a bit of a battleground. Some purists argue that any sketch of Atticus Finch ruins the version living in your head. Others can't separate the characters from Gregory Peck’s face in the 1962 film. Yet, the history of illustrations for this novel is surprisingly rich, stretching from the early editorial sketches to the massive 2018 graphic novel adaptation by Fred Fordham.

👉 See also: The Apothecary Diaries Season 2 Episode 11: What You Probably Missed in the High Stakes Drama

The Evolution of the Maycomb Aesthetic

Visualizing a masterpiece is risky business. For decades, most people’s "drawings" of the book were actually just mental projections of the movie's set design. You know the one—the dusty streets, the high-collared dresses, the shadows on the Radley house. But early book club editions and international versions started experimenting with interior art long before the digital age.

Back in the day, illustrators had to capture the heat. You can almost feel the humidity in some of the scratchboard illustrations from the late 20th-century educational editions. These weren't always "pretty." They were jagged. They used heavy blacks and stark whites to mimic the moral binary Scout was trying to navigate. If you look at the work of illustrators like Edward Ardizzone, who worked on other mid-century classics, you see a specific kind of pen-and-ink tradition that influenced how schools commissioned To Kill a Mockingbird drawings for study guides.

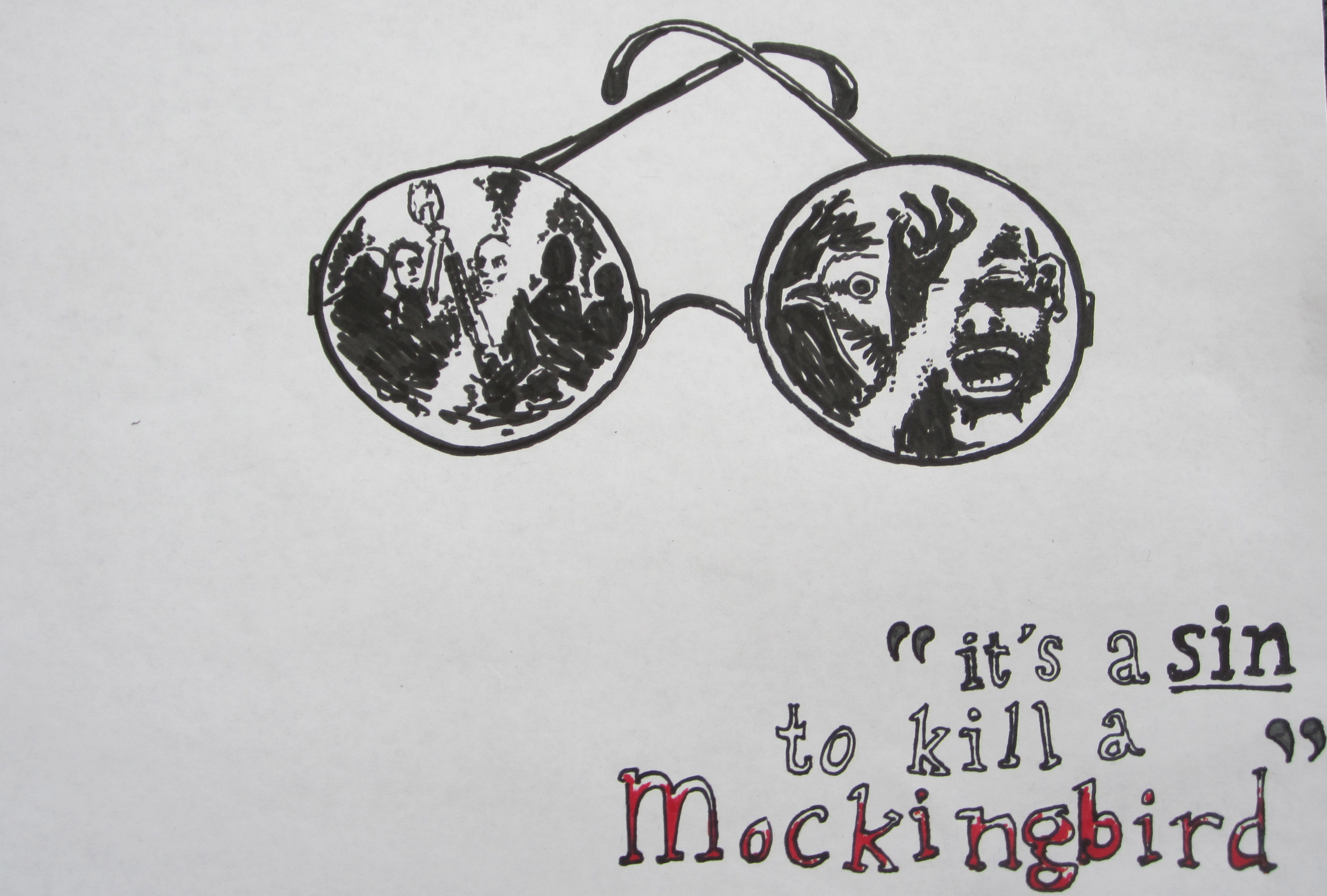

It’s about the "felt" experience. A sketch of a broken ham costume isn't just a costume; it's a symbol of surviving a murder attempt. A drawing of a mockingbird isn't just a bird; it’s a lesson in innocence. Artists have to balance the whimsical nature of Scout’s childhood with the crushing weight of the Tom Robinson trial. It's a hard line to walk.

The Fred Fordham Revolution

In 2018, the estate of Harper Lee did something people thought would never happen. They authorized a full-length graphic novel. This wasn't just a few doodles in the margins. It was a massive undertaking. Fred Fordham, the artist behind it, had a monumental task: how do you draw a book that everyone already "sees" in their mind?

Fordham spent a massive amount of time researching 1930s Alabama. He didn't just guess what the courthouse looked like. He looked at historical archives. His To Kill a Mockingbird drawings in the graphic novel use a muted, cinematic palette. The colors feel sun-bleached. It’s like looking at an old photograph that’s been brought to life with watercolor.

What’s interesting is how he handles Atticus. He avoids making him look exactly like Gregory Peck, which is a bold move. Instead, he focuses on the posture—the slightly slumped shoulders of a man carrying the weight of a town's sins. The drawings of Scout are equally intentional. She’s messy. She’s a tomboy. She doesn't look like a polished child actor; she looks like a kid who spends her time in the dirt.

Why We Keep Sketching the Radley House

There is one specific image that dominates the world of To Kill a Mockingbird drawings: the Radley house.

Why? Because it’s the ultimate mystery. In the first half of the book, the house is a monster. It’s a "malevolent phantom." Artists usually depict it with shuttered windows that look like closed eyes. It’s the architectural embodiment of fear.

But look at how the drawings change by the end of the narrative.

As Scout matures, the sketches of the house in various editions often become softer. The shadows aren't as long. The porch seems reachable. This visual shift mirrors the internal growth of the characters. If you’re looking at fan art on sites like DeviantArt or Instagram today, you’ll see a massive divide. Younger artists often lean into the "Southern Gothic" vibe—lots of moss, dark ink washes, and eerie silhouettes. Older, more traditional illustrators tend to focus on the courthouse scenes, emphasizing the rigidity of the law through straight lines and formal compositions.

The Symbolism of the Knot-Hole Sketches

If you’re looking for the heart of the book’s visual identity, look at the gifts in the tree. The grey twine. The two soap dolls. The tarnished medal. The pocket watch.

These objects are the most frequently drawn items in the fandom. Why? Because they are tactile. They are small pieces of humanity left by a "monster." When artists create To Kill a Mockingbird drawings focusing on these objects, they are participating in the same act of communication that Boo Radley was.

- The Soap Dolls: These are particularly haunting. In drawings, they usually have a slightly rough, hand-carved texture. They represent Boo’s perception of the children—fragile and carved from his own silent observation.

- The Mockingbird: Often drawn in a minimalist, literal style, it serves as the "logo" of the book’s themes. You’ll see it on everything from first-edition tattoos to classroom posters.

- The Courthouse: Usually depicted from a low angle to make it look imposing, representing an inaccessible justice.

The Problem With "Official" Art

There’s a tension here. Harper Lee was famously private. She didn't want her work commercialized in a way that felt cheap. For a long time, this meant that the only "official" art was the cover. This lack of visual saturation is actually what allowed the To Kill a Mockingbird drawings created by fans and students to flourish.

Every year, thousands of students are tasked with drawing a scene from the book. These aren't professional masterpieces. They are raw. They are drawings of a red-faced Bob Ewell or a terrified Mayella. This "folk art" of the novel is arguably more important than any professional gallery. It shows how the book’s themes of empathy and "walking in someone else's shoes" are being processed by new generations.

When you draw a character, you have to look at them. You have to decide what their eyes look like when they’re lying. You have to decide how Atticus holds his pen. That act of drawing is an act of deep reading.

Critical Perspectives on Visual Representation

Some critics, like those who analyze the racial dynamics of the South, point out that historical To Kill a Mockingbird drawings often centered the Finch family while leaving Tom Robinson and the Black community of Maycomb in the background or in silhouette.

Modern illustrators are changing that.

Contemporary artists are now focusing more on the dignity of Tom Robinson. They are drawing the "First Purchase" church with more detail and vibrancy, moving away from the "white savior" visual narrative and toward a more holistic view of the community. This shift in To Kill a Mockingbird drawings reflects our changing cultural conversation about the book itself. We aren't just looking at Scout’s porch anymore; we’re looking at the whole town, including the parts that were hidden in the shadows of the original 1960s perspective.

Technical Elements: How to Illustrate the 1930s South

If you’re an artist looking to tackle this subject, you can't just draw a generic "old" town. You need specificity.

- Texture is everything. The 1930s South was dusty. Your drawings should feel "gritty." Think about using charcoal or stippling to get that sense of heat and earth.

- Clothing speaks volumes. Scout’s overalls aren't just fashion; they are a rebellion against Aunt Alexandra’s tea parties. The way the fabric hangs tells the story of her character.

- Light and Shadow. The book is built on the "unseen." Use heavy chiaroscuro—the contrast between light and dark—to represent the secrets of the Radley house versus the blinding light of the courtroom.

The most successful To Kill a Mockingbird drawings aren't the ones that look like a photograph. They are the ones that capture the feeling of a long, hot summer where everything changed. They capture the moment Scout realizes that the world isn't as fair as she thought.

Moving Beyond the Page

We see the influence of these visuals in unexpected places. From stage play posters on Broadway to mural art in Monroeville, Alabama (Lee's hometown), the imagery of the mockingbird and the oak tree has become a shorthand for American morality.

Interestingly, the 2018 Broadway play by Aaron Sorkin opted for a very minimalist set design. It didn't try to "draw" Maycomb with literal buildings. It used pieces of a courtroom and a porch that moved in and out of the dark. This mimics the way a sketch works—giving you just enough lines to let your imagination fill in the rest.

Whether it's a professional graphic novel or a sketch in a high schooler's notebook, To Kill a Mockingbird drawings continue to serve as a bridge. They bridge the gap between Harper Lee's words and our own visual reality. They help us process the "ghoul" that becomes a hero and the "hero" who is just a man trying to do his best.

Actionable Steps for Artists and Readers

If you want to explore the visual world of Maycomb further, don't just stick to the movie posters.

- Study the Fred Fordham Graphic Novel: It’s a masterclass in pacing and historical research. Pay attention to how he uses panel borders to create a sense of claustrophobia during the trial.

- Look at WPA-era Photography: To understand the "real" drawings of the era, look at the work of Dorothea Lange or Walker Evans. These photos are the visual DNA of the book's setting.

- Create Your Own "Knot-Hole" Inventory: Try sketching the items found in the tree. Focusing on small objects can often reveal more about a character than trying to draw a full portrait.

- Analyze International Covers: Search for how To Kill a Mockingbird is illustrated in other countries. The Russian, Italian, and Japanese covers often use wildly different symbols—like cages or scales of justice—that provide a fresh perspective on the story.

The visual legacy of this novel is still being written. Every time someone picks up a pencil to sketch a mockingbird, they are engaging with a tradition that started in a small town in Alabama and ended up changing the way the world sees justice.