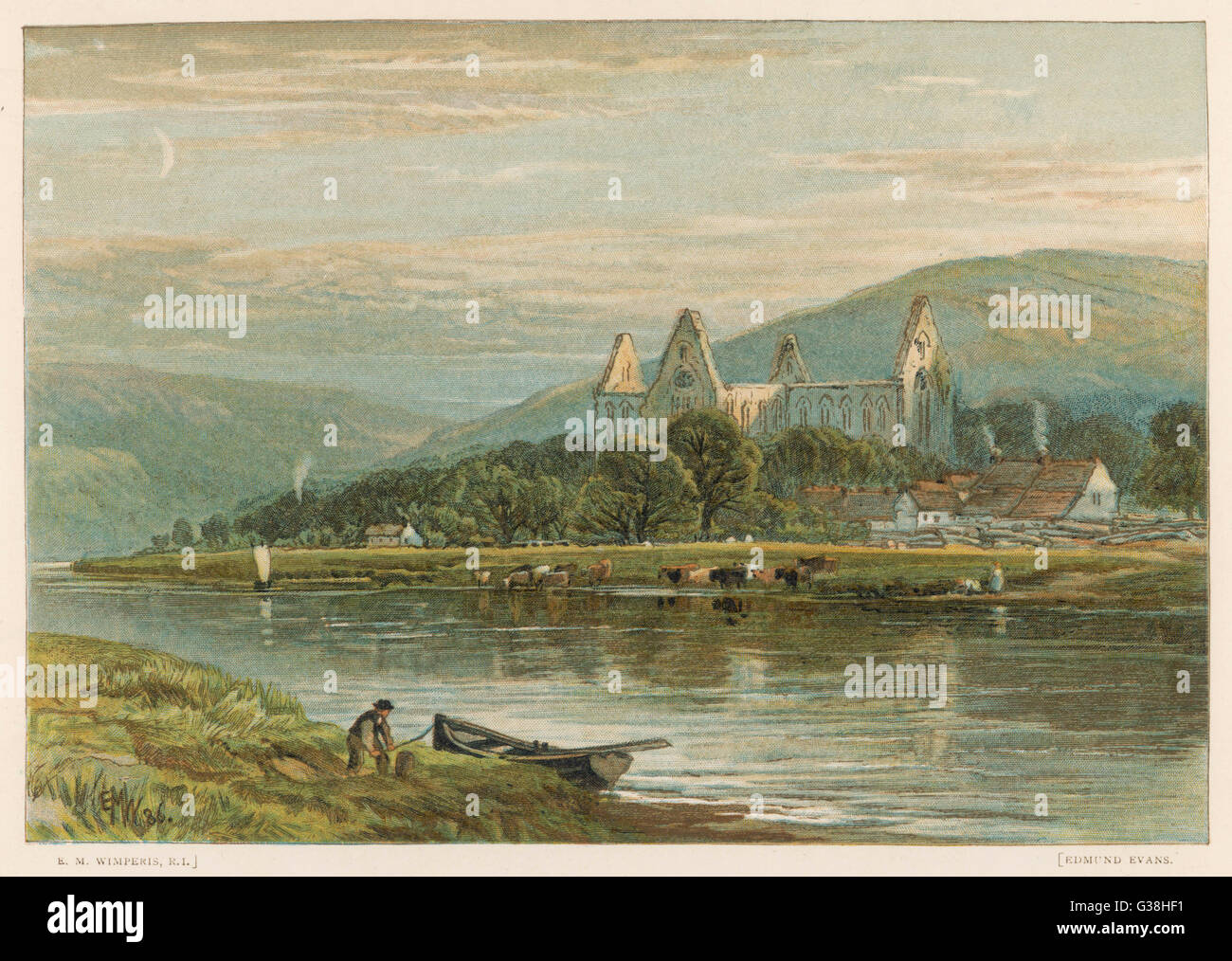

It was July 13, 1798. William Wordsworth was standing on a hill overlooking the Wye Valley. He wasn't some stuffy academic sitting in a library with a quill; he was a guy who had seen the world go sideways and needed a breather. This wasn't his first time here. He'd visited five years earlier, back in 1793, when he was basically a nervous wreck. If you’ve ever gone back to a favorite childhood spot just to see if you still feel the same spark, you’ve already lived the core of Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey. It is a poem about memory, but mostly, it’s about survival.

Most people think "Tintern Abbey" is about a ruin. It isn't. Wordsworth doesn't even describe the abbey. Honestly, he’s looking at the trees, the "plots of cottage-ground," and the "wreaths of smoke" rising from the woods. He is looking at how nature stays the same while he, the observer, has been chewed up and spit out by life. Between his first visit and this one, he’d lived through the French Revolution, fathered a child he couldn't see, and watched his political dreams dissolve into a bloody mess. He was exhausted.

What Lines Composed above Tintern Abbey is actually telling us

The full title is a mouthful: Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey, on Revisiting the Banks of the Wye during a Tour. July 13, 1798. That date matters. It was the eve of the anniversary of the Fall of the Bastille. Wordsworth was processing a massive personal and political hangover.

He talks about "beauteous forms." These aren't just pretty pictures. To him, these memories were a kind of mental medicine. When he was stuck in "lonely rooms" or amid the "din of towns and cities," he’d close his eyes and visualize the Wye Valley. It kept him sane. We call this "nature therapy" or "forest bathing" now, but Wordsworth was trying to figure out the mechanics of it two centuries ago. He realized that the way we see the world at twenty isn't how we see it at twenty-five.

The three stages of the soul

Wordsworth breaks down his life into three distinct phases in the poem. First, there’s the "boyish days." This was pure, unthinking physical reaction. He ran through the woods like he was escaping something. He says he was "more like a man flying from something that he dreads, than one who sought the thing he loved." It was all adrenaline and zero reflection.

Then comes the second stage. This is the 1793 visit. He’s a young man, deeply in love with the colors and sounds of the world. But it’s still mostly sensory. It’s an appetite. He calls it a "feeling and a love, that had no need of a remoter charm." He didn't need a philosophy back then; the sunset was enough.

🔗 Read more: Marie Kondo The Life Changing Magic of Tidying Up: What Most People Get Wrong

Finally, there’s the "now"—the 1798 version of William. This is where it gets heavy. He’s lost that "aching joy." It’s gone. But he isn't mourning it. Instead, he’s found something better: "the still, sad music of humanity." He’s learned to hear the interconnectedness of everything. He uses this famous phrase to describe a "sense sublime of something far more deeply interfused." Basically, he’s arguing that there’s a spirit or an energy that rolls through all things. It’s early Pantheism, and it was pretty radical for a guy who’d eventually become a conservative Poet Laureate.

The Dorothy Factor: Why the ending changes everything

You’re cruising through this deep, philosophical meditation on aging, and then suddenly, Wordsworth turns around and realizes his sister, Dorothy, is standing right there. The poem shifts from a monologue to a conversation.

He looks at Dorothy and sees his "former self." He sees in her eyes the same wild ecstasy he had five years ago. It’s a bittersweet moment. He’s basically saying, "Hey, life is going to beat you down too, and you’re going to lose this raw intensity, but it’s okay." He’s passing the torch. He wants the landscape to do for her what it did for him.

"Therefore let the moon / Shine on thee in thy solitary walk; / And let the misty mountain-winds be free / To blow against thee."

This isn't just sibling affection. It’s a prayer. He’s hoping that when she’s eventually dealing with "evil tongues" and "rash judgments," the memory of this walk will keep her heart soft. It’s arguably one of the most tender moments in all of British literature.

💡 You might also like: Why Transparent Plus Size Models Are Changing How We Actually Shop

Why the "Nature" label is kind of a lie

Scholars like Marjorie Levinson have pointed out something fascinating. Wordsworth leaves a lot out. In 1798, the Wye Valley wasn't some pristine wilderness. It was an industrial hub. There were ironworks. There were charcoal burners. The "wreaths of smoke" he mentions probably didn't come from cozy hermitages; they likely came from industrial furnaces.

By ignoring the industry and the poverty of the area, Wordsworth was performing a "selective seeing." He needed the valley to be a cathedral of nature so he could heal his psyche. He wasn't writing a documentary; he was writing a manifesto for the human spirit. He was choosing to see the "green to the very door" instead of the charcoal soot. Is that dishonest? Maybe. But it’s also how we all survive. We focus on the sunset, not the power lines running across it.

The "Tintern Abbey" legacy in the modern world

We live in a world of "din and confusion" that would make Wordsworth’s 18th-century London look like a library. We are constantly overstimulated. The reason Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey stays on every college syllabus isn't just because the meter is good. It’s because it provides a blueprint for "restorative environments."

Modern environmental psychology actually backs him up. The "Attention Restoration Theory" (ART) suggests that urban environments drain our cognitive resources, while natural environments allow them to replenish. Wordsworth called this "tranquil restoration." He was right.

Common misconceptions about the poem

- It’s about the ruins. Nope. The word "Abbey" never appears in the poem itself. Only the title.

- He’s depressed. He’s actually remarkably optimistic. He’s found a "compensating" strength.

- It’s an ode to God. It’s more an ode to the "Life Force" or the "Mind of Man." It’s very psychological.

Actionable Insights: How to read (and live) like Wordsworth

If you want to actually get what Wordsworth was talking about, don't just read the poem in a fluorescent-lit room.

📖 Related: Weather Forecast Calumet MI: What Most People Get Wrong About Keweenaw Winters

Find your "Wye Valley." Identify a place you visited five or ten years ago. Go back. Don't look at your phone. Observe what has changed in the landscape, but more importantly, observe what has changed in your "internal weather." Are you looking for the same things?

Practice "Double Vision." When you look at a landscape, try to see it as it is and as you remember it. Wordsworth’s power came from the "recognition" of what he had lost versus what he had gained. This creates a sense of continuity in your life.

Use the "Picture of the Mind." Wordsworth explicitly mentions that he carries these visual memories like a "food" for future years. If you’re in a beautiful place, take a mental "long-exposure" shot. Store it. Use it later when you’re stuck in traffic or a soul-crushing meeting.

Listen for the "Music of Humanity." Stop looking for "pure" nature. Accept the smoke and the power lines. Realize that the human struggle is part of the landscape, not separate from it. That’s where the "sublime" actually lives.

The poem concludes with a sense of duty. Wordsworth isn't just enjoying the view; he’s taking responsibility for his own mental health and for the emotional well-being of his sister. He’s teaching us that the "language of the sense" is the anchor of our purest thoughts. It’s a reminder that no matter how much the world changes—or how much we break—the woods are still there, the river is still flowing, and the memory of a green hill can be enough to get you through the night.

To dive deeper, look into the Lyrical Ballads of 1798. This poem was the grand finale of that collection. It was the moment Romanticism stopped being a theory and started being a lived experience. It’s messy, it’s contradictory, and it’s profoundly human.