David Bowie was bored. It was 1987, and he was standing on a stage surrounded by giant spiders and glass moths, singing "Glass Spider" to stadiums full of people who didn't really seem to care about the new stuff. He was a global superstar, a brand, a corporate entity. He hated it. He needed to disappear, so he did something that absolutely baffled the music industry: he joined a band. Not "David Bowie and the Band," but just Tin Machine.

Most people remember Tin Machine as a punchline. Or they don't remember them at all.

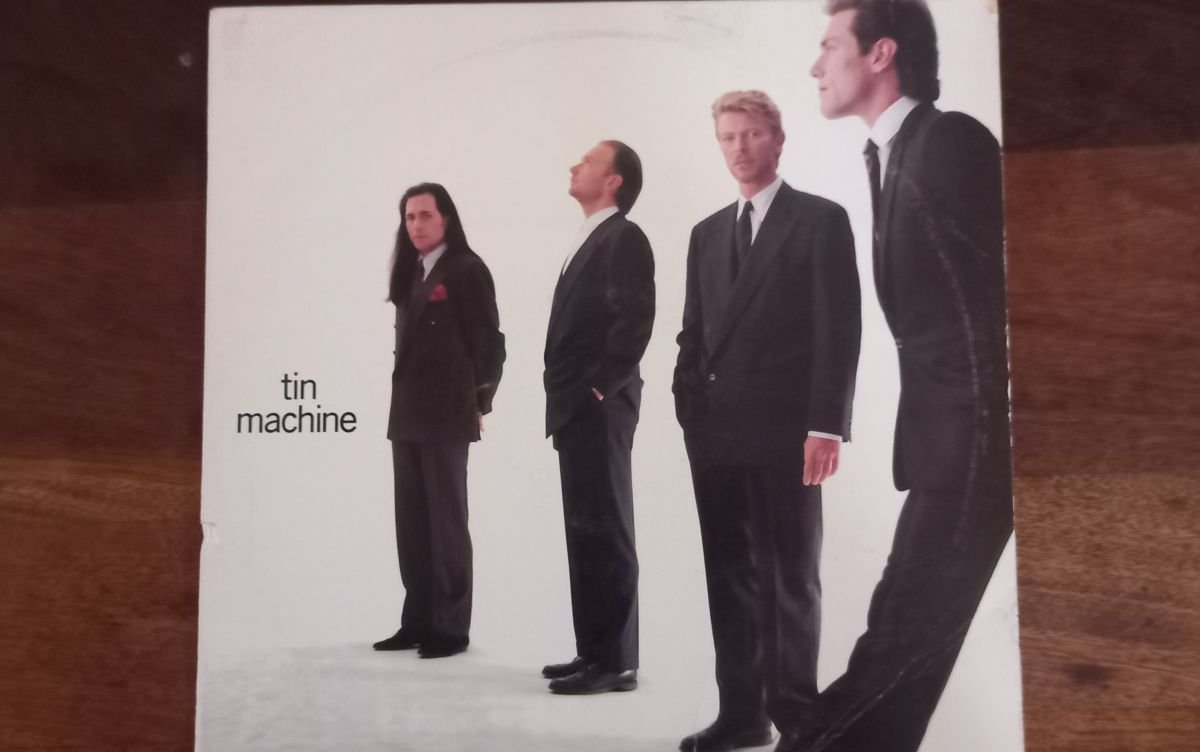

You've probably heard the jokes about the beards. Critics at the time were brutal, calling the project a mid-life crisis caught on tape. But if you actually sit down and listen to that first self-titled record from 1989, it doesn't sound like a crisis. It sounds like a riot. It’s loud. It’s abrasive. It’s honestly kind of a mess, but it’s a deliberate mess. Bowie wasn't the frontman; he was just the rhythm guitarist and singer who split the paycheck four ways with Reeves Gabrels and the Sales brothers, Hunt and Tony.

The Sound of a Legend Self-Destructing

When Tin Machine arrived, the charts were dominated by polished synth-pop and hair metal. Bowie decided to pivot toward a raw, proto-grunge sound that predated Nirvana’s Nevermind by two years. Reeves Gabrels played guitar like he was trying to break the instrument. There was no MIDI. No synthesizers. No "Let's Dance" glitter.

It was just four guys in a room recording mostly live takes.

The lyrics were weirdly literal for Bowie. Instead of the metaphorical alien landscapes of Ziggy Stardust, he was shouting about urban decay, drugs, and neo-Nazis. On the track "Under the God," he tackled racism with a bluntness that made people uncomfortable. It wasn't "artistic" in the way people expected from him. It was sweaty.

Honestly, the chemistry was the point. Hunt Sales played drums like he was hitting a heavy bag. Tony Sales kept the bass locked in a way that felt dangerous. Bowie had worked with them before on Iggy Pop’s Lust for Life, and he wanted that chaotic, impulsive energy back. He was tired of being the "Thin White Duke." He just wanted to be a guy in a suit playing loud rock and roll.

Why the Critics Went for the Throat

People didn't want a band. They wanted a star.

The media couldn't handle the democratic nature of the group. During interviews, Bowie would often sit back and let Reeves or the Sales brothers take the lead. Journalists felt cheated. They came for the legend and got a garage band. The 1991 follow-up, Tin Machine II, didn't help things much with its controversial cover featuring Kouroi statues.

Marketing was a nightmare. The label didn't know how to sell "Bowie-as-equal."

But looking back, you can see how much he needed this. Without Tin Machine, we probably wouldn't have gotten the industrial experimentation of Outside or the drum-and-bass influences of Earthling. This was his palate cleanser. He had to burn down the 80s superstar version of himself to see what was left in the ashes.

🔗 Read more: Kevin Hart and Ice Cube Conan: Why This 2016 Video Still Beats Everything on TikTok

The Legacy of the Noise

If you go back to the 1989 debut, tracks like "I Can't Read" show a vulnerability Bowie hadn't touched in years. It’s a song about feeling incompetent and lost. It’s beautiful and jagged.

Reeves Gabrels ended up staying with Bowie for over a decade. That partnership changed everything. Gabrels pushed Bowie to stop playing it safe, to embrace the dissonant and the difficult. If you like the guitar work on the Hours album, you owe a debt to the loud, clattering experiments of the late 80s.

It's funny. You look at bands like Pixies or Sonic Youth, and they get all the credit for that era's alternative shift. But Tin Machine was right there in the trenches, making a glorious racket that most of Bowie's fanbase was too scared to follow.

What We Get Wrong About the Project

There’s this idea that Tin Machine was a failure because they didn't sell millions of copies or top the Billboard charts. That’s a corporate way of looking at art.

Bowie himself called it "essential" for his sanity.

- It broke his addiction to stadium-filling pop tropes.

- It introduced him to his most important collaborator of the 90s.

- It allowed him to play small clubs again, regaining his edge.

The live shows were legendary for being unpredictable. Sometimes they were brilliant; sometimes they were an absolute train wreck of feedback and shouting. That’s rock and roll, isn't it? It’s supposed to be a little bit falling apart at the seams.

How to Listen to Tin Machine Today

Don't start with the second album. It’s a bit too polished in some spots and too aimless in others.

Go back to the 1989 debut. Turn it up. Don't look for the "Starman." Look for the guy who was trying to find his soul again. Listen to the title track, "Tin Machine," and notice how the drums seem to be chasing the vocals. It’s restless.

If you want to understand the modern appreciation for the band, look at the 2019 box set Spying Through a Keyhole or the various live recordings that have surfaced. You’ll hear a band that was genuinely having fun, even when the world was telling them to stop.

Actionable Steps for the Curious Listener

If you’re ready to dive into this weird corner of music history, don't just stream the hits.

- Watch the "Oy Vey, Baby" live video: It’s chaotic and captures the band’s physical energy better than the studio tracks.

- Listen to the 1989 BBC Sessions: These versions of the songs are often tighter and more aggressive than the album versions.

- Compare "I Can't Read" (Tin Machine version) to the 1997 solo remake: You can hear how the song evolved from a band jam into a haunting electronic piece.

- Ignore the beards: Seriously, that was the biggest hang-up people had in the 80s. It doesn't affect the audio.

Tin Machine wasn't a mistake. It was a bridge. It was the sound of a man reclaiming his right to be loud, messy, and unpopular. In a world of curated personas and perfect social media feeds, there is something deeply refreshing about a superstar who was willing to be just another guy in a band, even if it meant everyone laughed at him for a while.