You’re sitting there, maybe scrolling through your phone or drinking a lukewarm coffee, and suddenly it hits you that it’s already the middle of the year. Or maybe you just realized that 2019 was over half a decade ago. It feels wrong. It feels like a heist where someone is stealing your days while you're looking right at them. We’ve all felt that weird, sinking sensation of time flying by so fast, but it turns out your brain isn't actually losing track of the clock. It’s just getting efficient. Too efficient for its own good.

The phenomenon is real. It’s not just "getting older."

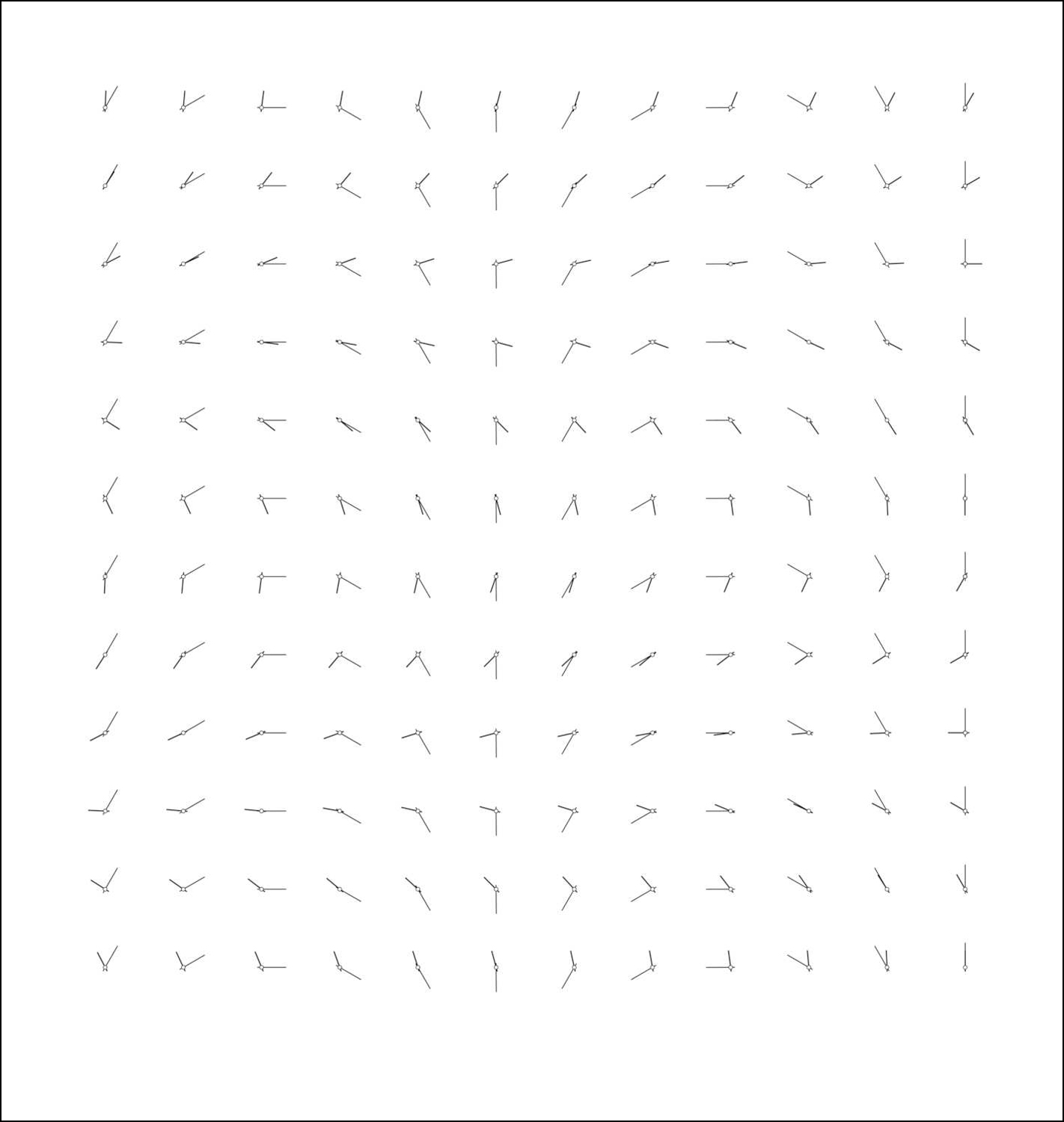

There is a psychological term for this called the "reminiscence bump," but that only explains part of why your thirties feel like a weekend while your childhood felt like an epoch. When you were ten, a single summer felt like a lifetime because everything—the smell of cut grass, the physics of a bicycle, the taste of a specific brand of soda—was brand new data. Your brain was recording in 4K resolution, capturing every frame. Now? Your brain is on autopilot. It sees a commute, a desk, a dinner, and a bed, and it basically says, "I've seen this movie before," and hits the fast-forward button on the recording.

The Neurological Shortcut Making Time Fly

David Eagleman, a neuroscientist at Stanford, has spent a massive chunk of his career studying time perception. He found that the more familiar a stimulus is, the less energy the brain uses to process it. Think about the first time you drove to a new job. The route felt long. You noticed the weirdly shaped tree, the pothole near the intersection, and the specific billboard for personal injury lawyers.

By day 500? You get to work and realize you don't even remember the drive.

This "neural adaptation" is a survival mechanism. Our brains are designed to ignore the mundane to save energy for the unexpected. But the side effect is a total collapse of your internal timeline. When you look back at a week where you did the exact same things in the exact same order, your brain compresses those seven days into a single "event." If your life is a series of identical days, your memory file size is tiny. That’s why you blink and a month is gone.

The Math of Proportionality

There is also a very simple, albeit depressing, mathematical reality to time flying by so fast.

When you are 5 years old, one year is 20% of your entire existence. It’s a massive slice of the pie. When you are 50, that same year is only 2%. Logarithmically, each passing year represents a smaller and smaller fraction of your total experience. Paul Janet, a 19th-century French philosopher, was one of the first to propose this "proportional theory." He suggested that we perceive time relative to the absolute length of our lives. It’s a cruel bit of arithmetic that means the "subjective" middle of your life occurs much earlier than you think—some psychologists suggest it might even be in your early twenties.

Why Your Phone Is a Time Vacuum

It’s not just aging. It’s the glass rectangle in your pocket.

If you want to know why time flying by so fast has become a modern epidemic, look at your Screen Time report. Digital consumption creates a "flat" experience. When you spend three hours scrolling through TikTok or Instagram, you are processing thousands of micro-bits of information, but none of them are anchored to a physical space or a unique sensory experience.

You’re in a flow state, but a hollow one.

In a traditional "flow" state—like painting or playing a sport—you are engaged. In "digital flow," you are passive. Because there are no "temporal landmarks" (like a change in scenery or a physical challenge), the brain doesn't create distinct memory markers. You emerge from a two-hour scroll session feeling like only fifteen minutes passed, yet you feel exhausted. You've essentially deleted that time from your conscious narrative.

The "Holiday Paradox"

Have you ever gone on a busy, one-week vacation and felt like you were gone for a month? That’s the Holiday Paradox.

💡 You might also like: Exactly How Many Teaspoons is 1/4 of a Tablespoon and Why Your Recipes Fail

During the trip, time might feel like it’s moving quickly because you’re having fun and stay busy. However, because you are constantly encountering new sights, sounds, and experiences, your brain is laying down a massive amount of new memory data. When you return home and look back, the "density" of those memories makes the week feel incredibly long.

Contrast that with a week at the office.

While you're sitting at your desk, the day might feel like it's dragging on forever. You’re checking the clock every ten minutes. But when you look back on Friday, the week is a total blur. This is the great irony of human existence: boring time feels slow in the moment but fast in retrospect, while exciting time feels fast in the moment but long in memory.

Breaking the Speed of Life

If you want to stop time flying by so fast, you have to stop being so efficient. You have to introduce "cognitive friction."

This doesn't mean you need to quit your job and go skydiving every Tuesday. It means you need to disrupt the autopilot. Research into "neuroplasticity" suggests that learning a new skill—literally any skill, from Japanese to juggling—forces the brain to step out of its energy-saving mode. When you’re a beginner, you’re forced to pay attention. That attention creates the "thick" memories that stretch out your perception of time.

✨ Don't miss: Why wearing a black dress with a cardigan is the only style hack you actually need

Try changing your environment.

Even something as small as taking a different route to the grocery store or eating dinner in a different room can create a tiny temporal landmark. Our lives are often built around minimizing friction—ordering the same food, watching the same types of shows, talking to the same three people. We are optimizing ourselves into a blur.

The Role of Stress and Cortisol

We also can't ignore the biological impact of chronic stress. When you're constantly "on," your brain is stuck in a state of high-alert processing. While acute fear can make a second feel like an hour (the classic "car crash" effect where everything moves in slow motion), chronic, low-grade stress does the opposite. It makes us focus so intensely on the "next thing" on our to-do list that we never actually inhabit the "current thing."

We are living in the future, which makes the present disappear.

Actionable Steps to Slow Things Down

You can't stop the clock, but you can change how your brain archives the footage. It's about density, not duration.

- The "First Times" Rule: Aim for one "first" every week. It can be a new recipe, a new park, or even just a new genre of music. Newness is the only known antidote to the compression of time.

- Audit Your Transitions: We often lose time in the "gaps"—the 20 minutes between finishing work and starting dinner. Instead of scrolling, sit for five minutes and do nothing. Forcing yourself to experience "boredom" in the moment actually expands your perception of that day.

- Physical Memory Anchors: Print out photos. Our digital libraries are graveyards for memories. Holding a physical photo or writing a three-sentence journal entry at night forces the brain to "index" the day properly.

- Sensory Grounding: When you feel the week slipping away, pick three specific things you can see, smell, and feel right now. This breaks the "future-tripping" cycle and forces a temporal marker into the brain's timeline.

- Monotasking: Multi-tasking is a myth; it’s actually just rapid task-switching. It fragments your attention and prevents the formation of deep memories. Doing one thing at a time makes that thing "exist" in your memory.

The sensation of time flying by so fast is ultimately a signal that you've stopped learning and started repeating. Your brain is a master editor, and it's cutting out all the "boring" parts of your life to save space. To get your time back, you have to give the editor something worth keeping. Change the scenery, break the routine, and stop letting the days blend into one long, gray smudge. If you don't intentionally create landmarks, the road will always look shorter than it really is.