The lake, it is said, never gives up her dead when the gales of November come early. That’s not just a lyric. It’s a cold, hard fact of life for anyone living near Lake Superior. On November 10, 1975, the SS Edmund Fitzgerald, a massive iron ore freighter, simply vanished from radar near Whitefish Point. No distress call. No screaming over the radio. Just a 729-foot ship and 29 men swallowed by twenty-five-foot waves. For decades, the public only had their imaginations to fill in the blanks. Then came the cameras. When people look for Edmund Fitzgerald wreckage photos, they aren't just looking for rust and twisted steel; they are looking for answers to a mystery that has stayed stubbornly unsolved for over fifty years.

Superior is different. It’s cold. Really cold. At the depths where the "Fitz" rests—about 530 feet down—the water stays a constant, bone-chilling temperature just above freezing. This creates a natural refrigerator. While ships in salt water decay or get covered in coral, the Fitzgerald looks eerily preserved. It’s haunting. Honestly, looking at the images captured by ROVs (Remotely Operated Vehicles) and manned submersibles over the years feels like peering into a fresh grave. You can see the "Fitzgerald" nameplate clearly. You can see the pilot house windows blown out. You can see the massive structural failure that snapped the ship in two.

The story behind the first Edmund Fitzgerald wreckage photos

The search didn't take long, but finding the ship and seeing the ship are two very different things. A U.S. Navy Lockheed P-3 Orion aircraft found the wreck site using magnetic anomaly detection just days after the sinking. But we didn't get eyes on it until 1976. That’s when the CURV III, an underwater recovery vehicle, went down.

The photos were grainy. Black and white. Terrifying.

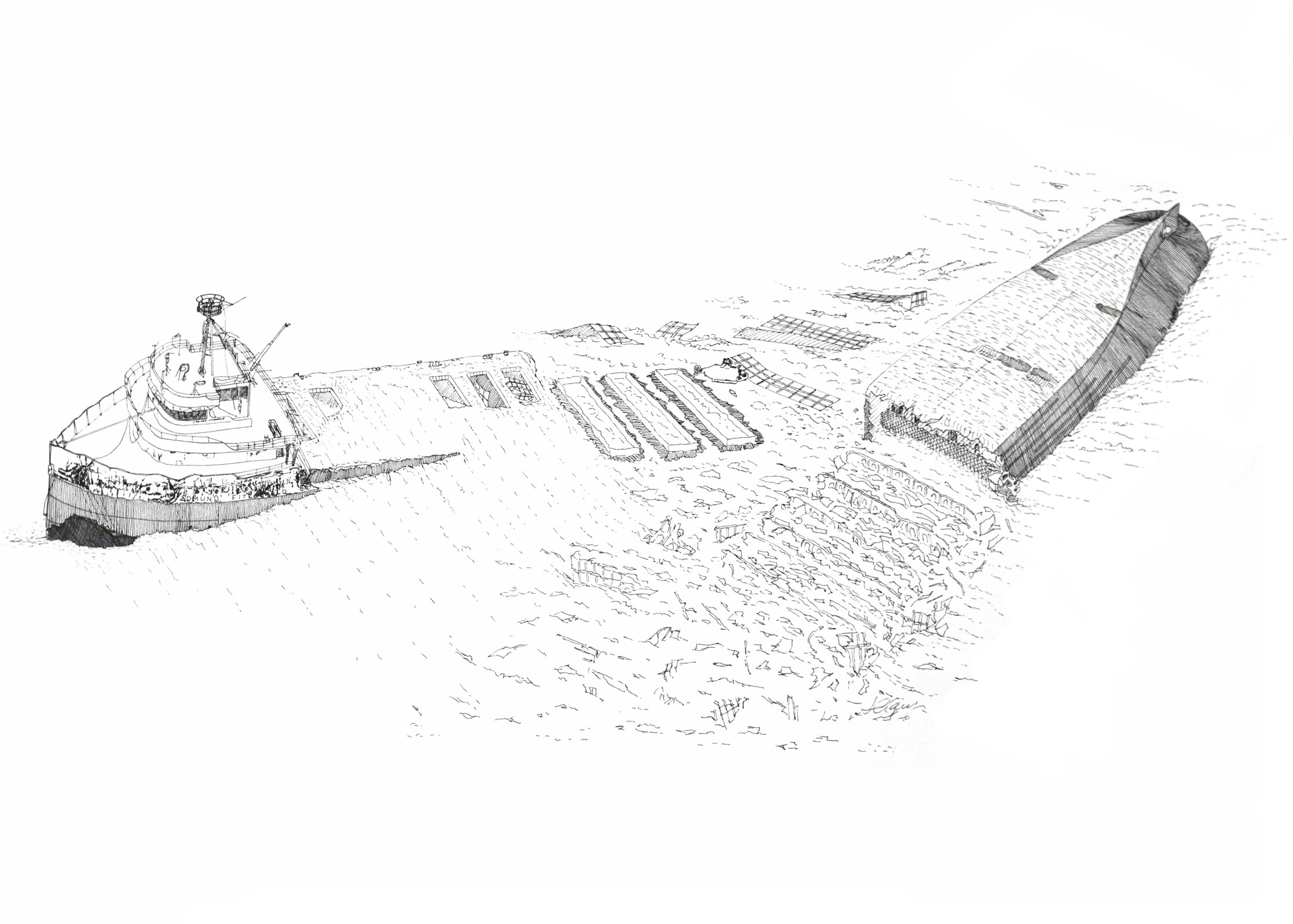

They showed the bow sitting upright, looking almost proud despite the devastation. The stern, however, was a different story. It was flipped upside down, sitting about 170 feet away from the front half. The middle of the ship? Total chaos. It was pulverized. These initial Edmund Fitzgerald wreckage photos proved the ship didn't just sink; it broke apart with a violence that’s hard to wrap your head around. Imagine a 700-foot steel skyscraper being snapped like a toothpick. That’s what the camera saw.

Why the 1994 and 1995 expeditions changed everything

Technology caught up with the mystery in the mid-90s. This is where the most famous, high-definition images come from. MacInnis, a Canadian explorer, and the crew of the Shannon used a Newtsuit—basically a one-man submarine that looks like a spacesuit—to get close. This was the expedition that really localized the human element of the tragedy.

They weren't just looking at rivets anymore.

💡 You might also like: JD Vance River Raised Controversy: What Really Happened in Ohio

They found the ship's bell.

They found personal effects.

Then came the controversy. In 1994, a diving team led by Fred Shannon captured footage that allegedly showed the remains of a crew member near the stern. This changed the conversation about Edmund Fitzgerald wreckage photos forever. It stopped being a maritime puzzle and became a cemetery. The families of the 29 men lost were, understandably, devastated. They didn't want their loved ones' final resting place turned into a tourist attraction or a morbid gallery for the internet to gawk at.

What the photos actually tell us about how she sank

There are three main theories. People argue about this in Duluth bars and maritime museums to this day.

- The Shoaling Theory: The ship hit the Caribou Island reef, scraped its bottom, and took on water slowly until it lost buoyancy.

- The Hatch Cover Theory: The crew didn't secure the hatches properly, and massive waves swept over the deck, filling the hold.

- The Rogue Wave Theory: Three massive waves—often called the "Three Sisters"—hit the ship in quick succession, driving the bow underwater where it hit the bottom while the engines were still pushing forward.

The Edmund Fitzgerald wreckage photos support the "nose-dive" idea more than anything else. When you look at the bow, it’s buried deep in the mud. The mud is shoved up into the crevices of the steel. This suggests the ship was moving with incredible force when it hit the floor of Lake Superior. It didn't just drift down. It flew down.

The legal battle over the images

Because of the 1994 discovery of human remains, the families pushed for a ban on diving. They succeeded. The Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society and the Canadian government stepped in. Today, the wreck is a protected site. You can't just go down there with a GoPro.

📖 Related: Who's the Next Pope: Why Most Predictions Are Basically Guesswork

Actually, it's basically illegal to dive on the site without a very specific, hard-to-get permit from the Ontario Ministry of Citizenship, Culture and Recreation. This is why you don't see "new" Edmund Fitzgerald wreckage photos popping up on Instagram. The images we have are historical artifacts. They are a finite set of windows into 1975.

The psychological weight of the "Fitz"

Why are we so obsessed with this one ship? There are over 6,000 wrecks in the Great Lakes. Many had higher death tolls. But the Fitzgerald was the flagship. It was the biggest. It was the "Pride of the American Side."

The photos capture the death of an era. The 1970s were a time when we thought we had conquered nature with big steel and loud engines. Superior proved us wrong. When you look at the photo of the bent crane on the deck, or the tattered remains of the lifeboats (which were found empty, by the way), you're looking at a reminder of human fragility.

It's also about the song. Gordon Lightfoot’s ballad gave the ship a soul. When you see the photo of the bell—the one they eventually recovered in 1995 and replaced with a replica engraved with the names of the 29—you can almost hear the tolling. That bell is now at the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum. It’s the only part of the ship most of us will ever see in person.

Misconceptions about the wreckage photos

A lot of people think there are photos of the entire ship sitting on the bottom. There aren't. Visibility in Lake Superior is decent, but not that decent. Most photos are "mosaics" or close-ups. You see a winch. You see the railing. You see the mud.

Another big misconception? That the ship is "rotting away."

👉 See also: Recent Obituaries in Charlottesville VA: What Most People Get Wrong

Nope.

Because Lake Superior is so cold and lacks the wood-eating organisms found in the ocean, the Fitzgerald is in remarkably good shape. If it weren't for the silt and the sheer force of the impact, she'd look like she could sail again. The paint is still visible in some shots. That’s the creepiest part. It doesn't look like a 50-year-old wreck. It looks like it happened last week.

Insights for the curious

If you are looking for the most authentic Edmund Fitzgerald wreckage photos, stick to the archives of the Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society or the footage from the National Geographic specials. Avoid the "creepy-pasta" side of the internet that uses AI-generated images or photos from different shipwrecks to bait clicks.

Realize that these images are essentially crime scene photos. They represent the moment 29 lives ended.

Next Steps for Deep Research:

- Visit the Museum: If you’re ever in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, go to Whitefish Point. Seeing the actual bell changes your perspective on the photos. It’s heavy. It’s real.

- Study the Marine Board of Investigation Report: Match the photos to the 1977 Coast Guard report. It’s a dry read, but it explains why the steel is twisted in specific directions.

- Respect the Boundary: Understand that the wreck is a gravesite. The lack of new photos isn't a conspiracy or a cover-up; it's a rare example of human decency winning out over the desire for content.

- Check the Weather: To understand the photos, look at the weather maps from Nov 10, 1975. Seeing the pressure drop on a map helps explain why the ship in those photos is in two pieces.