William "Boss" Tweed once famously barked, "I don't care a straw for your newspaper articles, my constituents don't know how to read, but they can't help seeing them damn pictures!" He was talking about Thomas Nast cartoons Boss Tweed and the devastating impact they were having on his criminal empire. It's wild to think about. In the 1870s, a guy with a pencil basically took down the most powerful political machine in American history.

Tweed wasn't just some local politician. He ran New York City. As the head of Tammany Hall, he controlled the courts, the police, and the treasury. If you wanted a job or a contract, you went through him. But Thomas Nast, a German-born illustrator for Harper’s Weekly, decided he’d had enough. He started drawing Tweed as a bloated, greedy vulture. People loved it.

The Art of Character Assassination

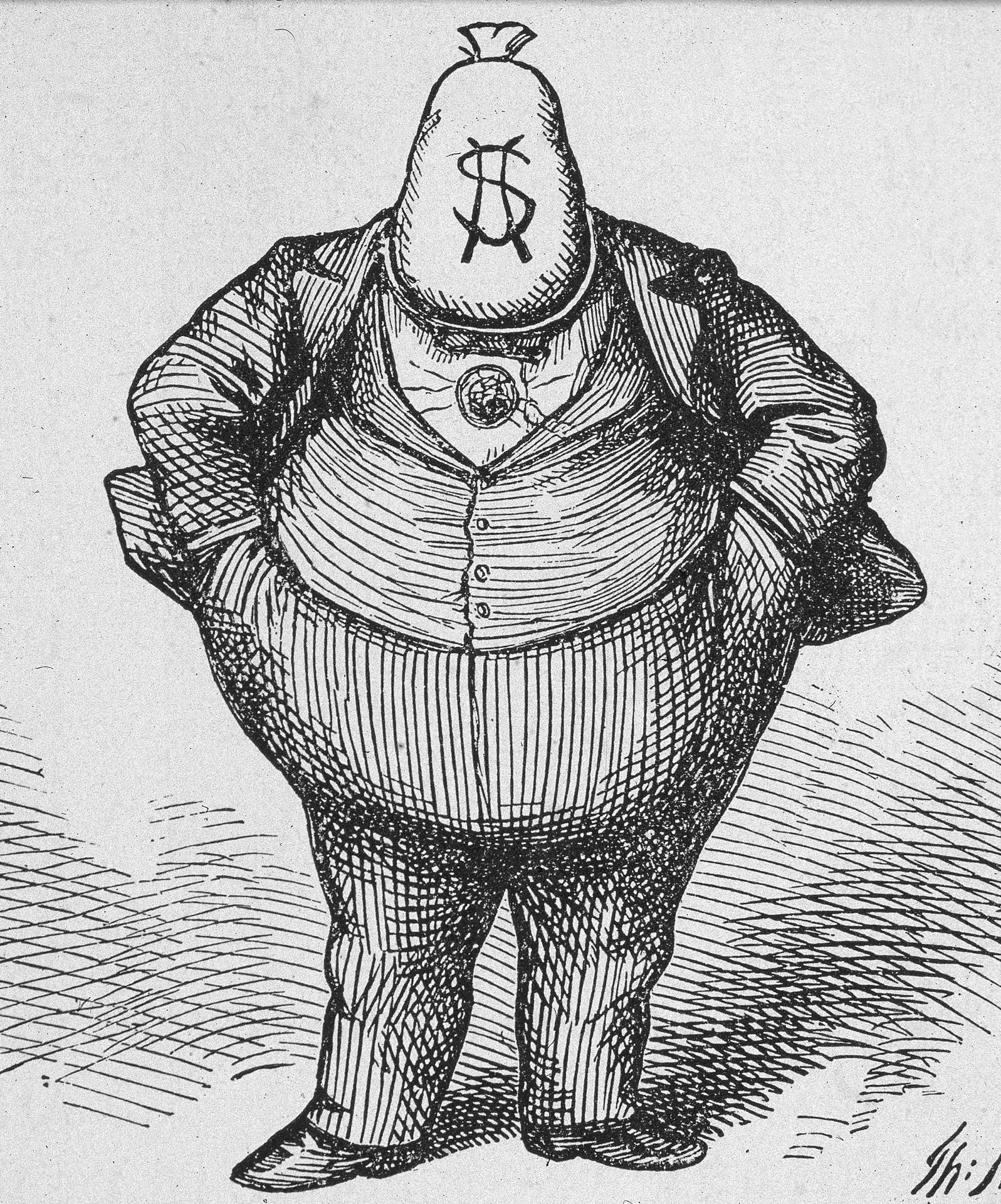

Thomas Nast didn't invent the political cartoon, but he perfected it as a weapon. Before him, cartoons were often wordy and stiff. Nast changed that. He gave Tweed a literal bag of money for a head in some drawings. In others, he showed the "Tammany Tiger" mauling the Republic.

It was brutal.

Honestly, the way Nast used Thomas Nast cartoons Boss Tweed to simplify complex corruption was genius. Most of Tweed’s supporters were poor immigrants. Many couldn't read English well, or at all. But they could see a drawing of Tweed leaning against a ballot box with the caption "Who counted the votes?" and they got the message immediately. Corruption isn't abstract when it's drawn as a man stealing from a child's pocket.

Nast's style was high-contrast and aggressive. He used cross-hatching to create deep shadows, making Tweed look like a villain out of a gothic novel. This wasn't just "satire." It was a targeted campaign to delegitimize a regime that everyone thought was untouchable.

The "Tammany Ring" and the $200 Million Heist

To understand why the cartoons worked, you have to understand the scale of the theft. The "Tammany Ring" consisted of Tweed and his three closest cronies: Peter Sweeny, Richard Connolly, and A. Oakey Hall. Together, they faked bills, overcharged for construction, and pocketed the difference.

Take the New York County Courthouse. They started building it in 1861. By the time they were "done," it had cost over $13 million. For context, the U.S. bought Alaska from Russia for $7.2 million around the same time. One plasterer, Andrew Garvey, was paid $133,000 in a single day for "repairs." Nast drew these men as a literal circle, each pointing to the man next to him with the caption "Twas Him."

✨ Don't miss: Why Every Tornado Warning MN Now Live Alert Demands Your Immediate Attention

Why Boss Tweed Feared a Cartoonist

Tweed tried to buy Nast off. He really did. He sent an emissary to Nast’s house offering him $100,000 to "study art in Europe." When Nast pushed, the offer went up to $500,000. That’s millions in today's money.

Nast’s response?

"I don't think I'll go. I made up my mind not long ago to put some of those fellows behind bars."

That kind of integrity is rare. Tweed knew that as long as Nast kept drawing, the public's perception was shifting. You can't bribe everyone, and you certainly can't bribe a guy who values his ink more than your gold. The cartoons created a visual language for the corruption. They made the "Tweed Ring" a household name for all the wrong reasons.

The Tiger and the Vulture

Nast’s iconography stuck. He gave the Democratic Party the donkey (though it had existed before, he popularized it) and gave the Republicans the elephant. But his most vicious work was reserved for the Tammany Tiger. Originally the symbol of a fire engine company Tweed belonged to, Nast turned it into a symbol of predatory greed.

In one of the most famous Thomas Nast cartoons Boss Tweed ever produced, titled "The Tammany Tiger Loose," the beast is seen in a Roman arena, tearing apart a woman representing the Republic. Tweed sits in the stands, looking on with a smirk. It was visceral. It made people angry.

The Downfall and the Great Escape

The end didn't happen overnight. It was a slow burn fueled by Nast's persistent imagery and some brave reporting by The New York Times. Eventually, the evidence of the "Secret Accounts" became too much to ignore. Tweed was arrested in 1873.

🔗 Read more: Brian Walshe Trial Date: What Really Happened with the Verdict

He didn't stay down, though.

Tweed managed to escape from jail in 1875 and fled to Spain. He probably thought he was safe. Spain didn't have a strong extradition treaty for his specific crimes. But he forgot one thing.

The cartoons.

A Spanish officer recognized Tweed. Not from a photograph—Tweed had never been photographed much—but from a Thomas Nast cartoon. Ironically, the officer thought Tweed was a child kidnapper because of a cartoon Nast had drawn showing Tweed griping a small child (representing the city). Tweed was arrested and sent back to the U.S. He died in jail in 1878.

The very images he hated ended up being the thing that put him back in a cell. Talk about poetic justice.

The Lasting Legacy of Nast’s Work

When we look at political memes today, we're looking at the descendants of Thomas Nast. He proved that an image could bypass the intellect and go straight to the gut.

- He defined the visual identity of American politics.

- He showed that the press could actually hold the powerful accountable.

- He sacrificed personal wealth for the sake of civic duty.

Of course, Nast wasn't perfect. Modern historians point out that his cartoons were often tinged with the prejudices of his time, particularly against Irish Catholics. He was a complex, often biased man. But his war against the Ring remains the gold standard for investigative art.

💡 You might also like: How Old is CHRR? What People Get Wrong About the Ohio State Research Giant

Practical Lessons from the Tweed Era

If you’re looking to understand how public opinion shifts today, look at the Nast vs. Tweed saga. It wasn't just about "the facts." Everyone knew Tweed was probably a crook. It was about making that crookedness feel intolerable.

Simplify the Message. Nast didn't explain the intricacies of municipal bonds. He drew a guy with a money bag for a head. If you're trying to communicate a complex issue, find the "money bag" metaphor.

Persistence Wins. Nast didn't draw one cartoon and quit. He drew hundreds. He hammered the same themes until they became reality in the minds of the public.

Visuals Trump Text. In a world of short attention spans, the "damn pictures" still carry more weight than a 5,000-word white paper. This is as true in 2026 as it was in 1871.

Identify the Core Villainy. Nast focused on Tweed's greed. By centering the corruption on a single, recognizable face, he gave the public a target for their frustration.

To see these works for yourself, you can visit the archives at the Library of Congress or the New York Historical Society. They hold original prints that show the incredible detail Nast put into every line. Seeing the yellowed paper and the sharp ink makes the history feel a lot less like a textbook and a lot more like a fight.

The story of Thomas Nast cartoons Boss Tweed serves as a reminder that power is fragile when people start to laugh at it—or when they finally see it for what it truly is.

How to Research Historical Political Cartoons

If you want to dig deeper into this era or find high-resolution versions of these cartoons for educational use, follow these steps:

- Access the Harper’s Weekly Archives: Many libraries provide digital access to the full run of the magazine from the 19th century. This allows you to see the cartoons in their original context alongside the news of the day.

- Search by Artist: Use the Library of Congress "Prints & Photographs Online Catalog" (PPOC) and search specifically for "Thomas Nast." You can filter by date (1870-1877) to find the Tweed-specific era.

- Analyze the Symbols: When looking at a Nast cartoon, look for the small details—the jewelry Tweed wears, the people in the background, and the labels on the walls. Nast often hid subplots in the corners of his drawings.

- Visit the Museum of the City of New York: They frequently host exhibits on Tammany Hall and have physical artifacts from the Tweed era, including furniture and documents that Nast referenced in his work.