Music moves fast. One minute you're the face of a banjo-led folk revolution, and the next, you’re standing in a studio in Johannesburg wondering if the world will let you change. That’s essentially the backdrop for "There Will Be Time," a collaboration that didn't just happen by accident. It was the result of a 2016 South African tour that could have been a standard "best of" run but turned into something much weirder. And better.

Mumford & Sons were at a crossroads. They had already dropped the acoustic guitars for Wilder Mind, a move that split their fanbase right down the middle. Some loved the electric, stadium-rock sheen; others felt like they’d been betrayed by the guys who made waistcoats and kick-drums cool again. Then came Baaba Maal.

The Johannesburg Connection

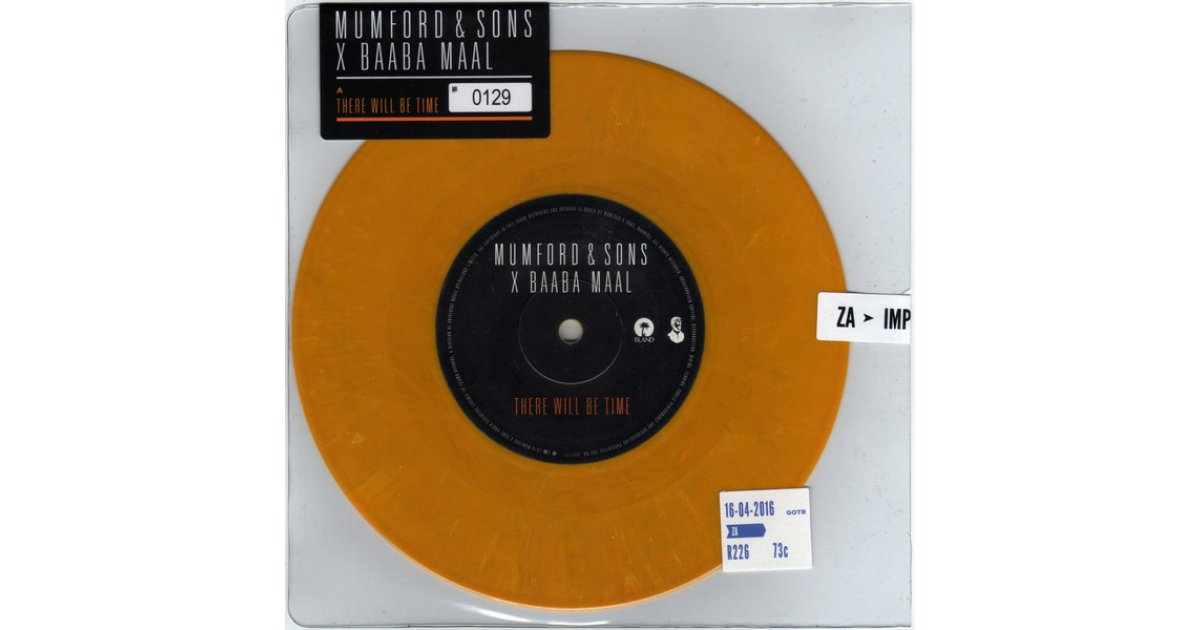

Most people think of "There Will Be Time" as just a single. It’s not. It is the beating heart of the Johannesburg EP.

Working with the legendary Senegalese singer Baaba Maal, alongside The Very Best and Beatenberg, Marcus Mumford and his crew basically threw the rulebook out the window. If you listen closely to the opening bars, you aren't hearing London. You’re hearing a frantic, beautiful collision of cultures. Baaba Maal’s voice enters like a force of nature. It’s high, haunting, and rhythmic in a way that Western folk-rock rarely manages to capture without sounding like a cheap imitation.

They didn't just "feature" these artists. They lived with them.

The recording sessions took place over just two days at the South African Broadcasting Corporation. Think about that for a second. Two days to write and record a track that would eventually hit number one on the Billboard Adult Alternative Songs chart. It shouldn't have worked. Usually, cross-continental collaborations feel forced. They feel like a marketing gimmick designed to tick boxes for "world music" playlists.

This felt like a conversation.

📖 Related: Why American Beauty by the Grateful Dead is Still the Gold Standard of Americana

Breaking Down the Sound of There Will Be Time Mumford and Sons

The song starts with a tease. You get that atmospheric, synth-heavy wash that defined their third album, but then the rhythm kicks in. It’s polyrhythmic. It’s messy. It’s alive.

Marcus Mumford’s vocals have always been criticized for being a bit "one note" in terms of intensity—he starts at a seven and ends at a twelve. But here, he’s forced to weave around Baaba Maal’s phrasing. The lyrics, "But in the cold light of the macrocosm / Without the ghost of a shadow of a doubt," feel massive. They feel like a man trying to find his footing in a universe that is way bigger than a pub in West London.

Honestly? It’s the best thing they’ve ever done because it’s the least "Mumford" thing they’ve ever done.

There’s no banjo. There isn't even a standard 4/4 folk stomp. Instead, you get this soaring, euphoric climax where Maal and Mumford are basically shouting at the heavens. It’s about the scarcity of time. It’s about the urgency of love. It’s the kind of song that makes you want to drive too fast on a highway at 2 AM.

What People Get Wrong About the Collaboration

A common misconception is that this was a pivot back to their "roots" because it used traditional instruments. It wasn't. It was a pivot into the unknown.

The critics were tough. Some said it was "tourist music." That’s a lazy take. If you look at the involvement of Johan Hugo from The Very Best, you see a deep respect for the electronic-meets-African-pop scene that has been thriving for decades. This wasn't Mumford & Sons colonizing a sound; it was them being invited into a space and having the humility to follow Baaba Maal’s lead.

👉 See also: Why October London Make Me Wanna Is the Soul Revival We Actually Needed

- The Lead Vocal: Baaba Maal sings primarily in Pulaar.

- The Recording Location: Studio 2 at SABC in Johannesburg.

- The Chart Success: It wasn't just a niche hit; it proved that mainstream audiences were hungry for something that didn't sound like a radio edit of a Coldplay song.

The Impact on the Band’s Legacy

Before "There Will Be Time," Mumford & Sons were in danger of becoming a parody of themselves. You know the memes. The suspenders, the dusty boots, the shouting about grace and sins. By leaning into the Johannesburg project, they bought themselves artistic license.

It allowed them to transition into Delta with a bit more dignity. It proved they could be a "global" band in the literal sense, not just a band that plays big festivals. The track remains a staple of their live sets for a reason. When those drums hit at the three-minute mark, the energy is undeniable.

The song also highlights a specific era of 2010s music where the lines between genres were finally starting to blur in a meaningful way. We were moving past the "indie folk" bubble and into something more textured.

How to Truly Appreciate the Track

If you’ve only heard the radio edit, you’re missing half the story. You need to hear it in the context of the full EP.

Listen to how "Wona" flows or how "Ngamila" sets the stage. There is a specific warmth to the production that feels like sunlight hitting a brick wall. It’s tactile. You can almost hear the room. That’s a rarity in an era where everything is quantized to death on a laptop.

Practical Insights for the Fan and the Curious

If you are looking to dig deeper into this specific sound or want to understand why this song still lingers on playlists years later, consider these points:

✨ Don't miss: How to Watch The Wolf and the Lion Without Getting Lost in the Wild

Look into Baaba Maal’s solo work. Specifically the album The Traveller. If you liked his contribution to the Mumford track, that album is the logical next step. It was produced by Johan Hugo as well, and it carries that same electric-organic energy.

Analyze the lyrics through a lens of transition. When Marcus sings about "There will be time," he’s talking about more than just a relationship. He’s talking about the lifespan of a band. He’s acknowledging that the frantic pace of fame isn't sustainable.

Watch the "Live from South Africa: Dust and Thunder" film. Seeing the song performed in its birthplace adds a layer of weight that the studio recording can't quite capture. The sweat, the dust, and the genuine look of surprise on the band's faces when the crowd reacts—it’s all there.

The reality is that "There Will Be Time" stands as a monument to what happens when big-name artists stop worrying about their "brand" and start worrying about whether a song feels honest. It’s loud, it’s chaotic, and it’s arguably the most vibrant five minutes of music produced in the last decade of British rock.

To get the most out of this track today, listen to it on a high-quality pair of headphones. Ignore the "folk" label. Ignore the "rock" label. Just listen to the way the two voices—one from Senegal, one from England—clash and then eventually find a way to dance together.

Next Steps for Deep Listening:

- Step 1: Find the Johannesburg EP on a high-fidelity streaming service (avoid low-bitrate versions to hear the percussion layers).

- Step 2: Compare the live version from the Pretoria show to the studio recording; the tempo fluctuates in the live version in a way that adds massive emotional stakes.

- Step 3: Explore the "making of" mini-documentary released by the band, which shows the literal 48-hour deadline they were working under, explaining why the song feels so breathless and urgent.