If you’ve ever driven down Highway 101 through Newport, you’ve seen it. That massive, salt-sprayed hunk of steel and concrete known as the Yaquina Bay Bridge Oregon. It’s not just a way to get from the north side of town to the south side. Honestly, it’s one of those rare pieces of infrastructure that actually makes you feel something when you drive over it. Maybe it’s the way the arches frame the Pacific, or perhaps it’s just the sheer "old world" vibe of the 1930s engineering.

It feels permanent. Solid.

But most people just fly over it at 45 miles per hour without realizing they’re crossing a masterpiece of the Great Depression. This bridge basically saved the Oregon Coast from being a series of disconnected, sleepy fishing villages. Before 1936, if you wanted to get across the bay, you were waiting for a ferry. Sometimes for a long time. Now, it’s the centerpiece of the Newport skyline, and it has a backstory that's way more interesting than just "it's a big bridge."

The Man Behind the Yaquina Bay Bridge Oregon

You can't talk about this bridge without talking about Conde McCullough. The guy was a legend. While most engineers at the time were just trying to get things to stand up, McCullough wanted them to look like art. He was obsessed with the idea that public works should be beautiful because the public had to look at them every day.

He wasn't wrong.

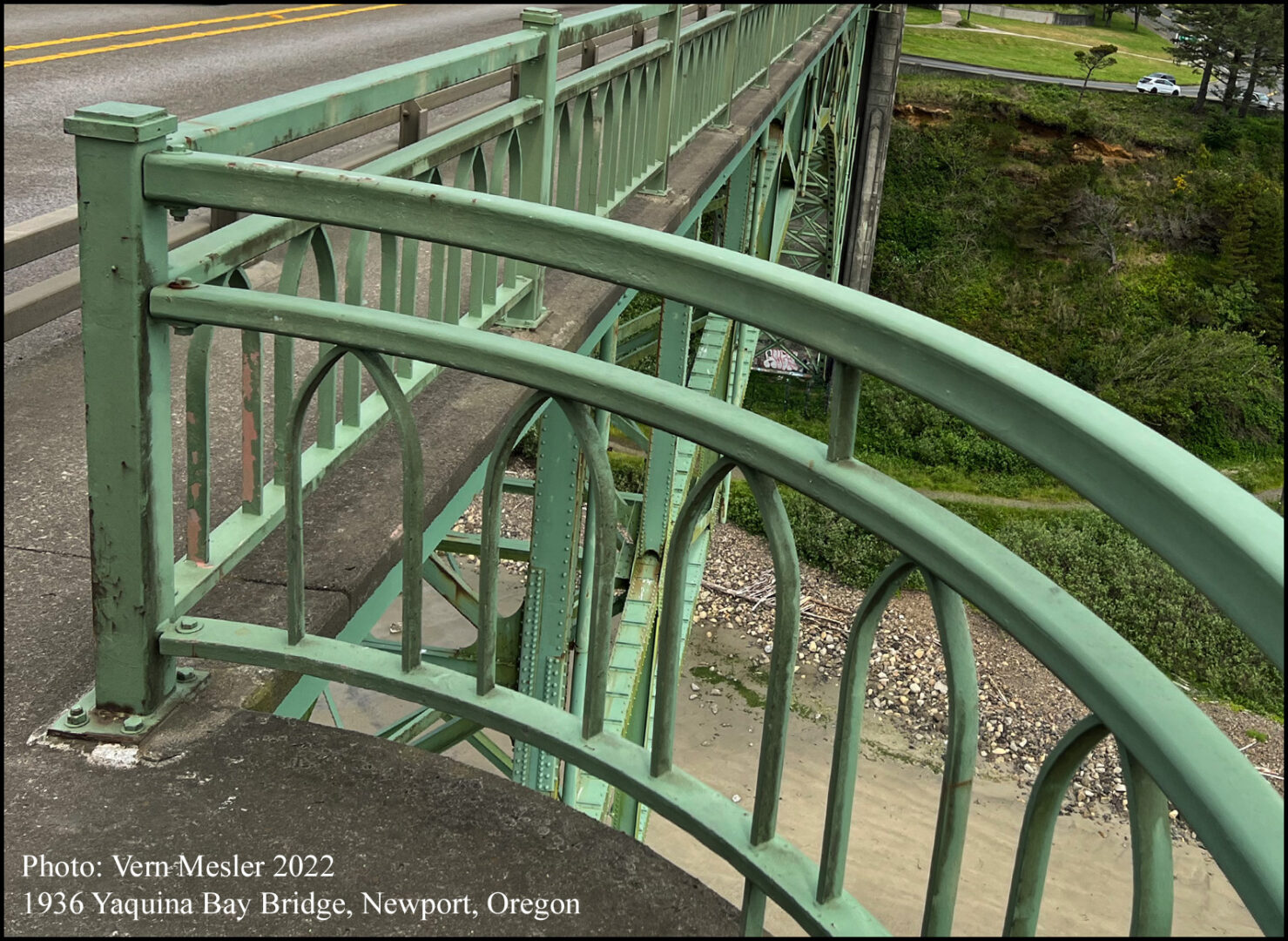

The Yaquina Bay Bridge Oregon is arguably his most famous work, though the one in Coos Bay gives it a run for its money. McCullough loved arches. He loved the way they distributed weight, sure, but he also loved the Gothic and Art Deco flourishes. Look closely at the pedestrian railings or the stairways. Those aren't accidents. They were intentional design choices meant to give the bridge a sense of "place."

Construction started in 1934. Imagine doing that work in the middle of the Depression. It was funded by the Public Works Administration (PWA), which was part of FDR’s New Deal. It put hundreds of local men to work at a time when Newport was struggling. They poured over 30,000 cubic yards of concrete. They used over 3,000 tons of steel. And they did it all in about two years. That’s faster than most modern pothole repairs take nowadays, which is kinda wild when you think about it.

✨ Don't miss: Getting Around the City: How to Actually Read the New York Public Transportation Map Without Losing Your Mind

A Mix of Steel and Concrete

What makes this structure unique is that it isn’t just one type of bridge. It’s a hybrid. You have the main steel arch in the middle—that's the 600-foot span that allows the big ships to pass through to the Port of Newport—and then you have these concrete "bowstring" arches on either side.

It’s a visual transition.

The steel part feels industrial and grand, while the concrete arches feel grounded. It’s also one of the few bridges where the "piers" (the legs in the water) are actually aesthetically pleasing. McCullough even designed the staircases so people could walk down from the bridge deck to the state parks below. He wanted people to interact with the bridge, not just use it.

Why Crossing It Can Be... Intense

Let's be real: driving across the Yaquina Bay Bridge Oregon for the first time is a bit nerve-wracking. The lanes are narrow. They were built for 1930s cars, not modern Ford F-150s or massive RVs heading to the South Beach State Park.

When a log truck passes you going the other way? Yeah, you’ll feel the vibration.

But that’s part of the charm. It’s a tactile experience. You’re 135 feet above the water at the highest point. On a clear day, you can see the Yaquina Bay Lighthouse to the north and the endless stretch of sand to the south. On a foggy day, which is about half the time in Newport, the arches disappear into the gray, and it feels like you're driving into a void. It’s incredibly atmospheric.

🔗 Read more: Garden City Weather SC: What Locals Know That Tourists Usually Miss

The Best Views (That Most Tourists Miss)

Most people just take a photo through their windshield. Don't do that. If you want the real experience, you've got to get out of the car.

- The Fishing Pier: On the south side of the bay, there’s an old section of the original road that leads to a fishing pier. It puts you directly underneath the concrete arches. The scale from down there is dizzying. You can hear the hum of the tires overhead, rhythmic and steady.

- Yaquina Bay State Park: This is on the north end. There are trails that wind through the trees and pop out at overlooks perfectly aligned with the bridge's main arch.

- The Newport Bayfront: If you head down to the historic bayfront (where the sea lions are screaming), look back toward the west. At sunset, the sun drops right through the center of the steel arch. It’s the "money shot" for photographers.

The Constant Battle with the Ocean

The Oregon Coast is a brutal environment for a bridge. You have constant salt spray, high winds, and moisture that never really goes away. The Yaquina Bay Bridge Oregon is essentially a giant piece of metal sitting in a saltwater bath.

Maintenance is a never-ending job.

ODOT (Oregon Department of Transportation) is constantly out there. You’ll often see those white "cocoons" wrapped around sections of the bridge. That’s not just for show; they’re sandblasting the old lead paint and applying new protective coatings. It’s expensive. We’re talking millions of dollars every few years just to keep the rust at bay.

There's also the seismic issue. Oregon is overdue for a "big one" (the Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake). Engineers have been working on seismic retrofitting for years, trying to ensure that this 1930s structure can handle a 21st-century disaster. They’ve added carbon fiber wraps and internal steel reinforcements. It’s a delicate balance of keeping the historical look while making it strong enough to survive a literal "end of the world" scenario.

The Mystery of the "Third" Staircase

There’s a bit of local lore about the secret spots of the bridge. While the main staircases are obvious, there are some maintenance walkways that look like they lead to Narnia.

💡 You might also like: Full Moon San Diego CA: Why You’re Looking at the Wrong Spots

People used to be able to explore more of the bridge’s underbelly, but security and safety concerns have closed off the "cool" parts. Still, if you walk the pedestrian path on the east side, you’ll see the intricate Art Deco light fixtures. Most are replicas now—the originals couldn't handle the salt—but they’re faithful to McCullough's vision. They look like something out of The Great Gatsby, which is a weird contrast to the rugged, fish-smelling docks below.

Practical Tips for Your Visit

If you're planning to stop at the Yaquina Bay Bridge Oregon, timing is everything. Traffic in Newport can be a nightmare during the summer, especially on weekends. Highway 101 narrows down right at the bridge, and it becomes a bottleneck.

- Avoid "Rush Hour": Mid-day on a Saturday in July? Forget it. You'll be crawling. Go early in the morning when the mist is still sitting on the water. It's quieter, and the light is better.

- Parking: Park at the Yaquina Bay State Park on the north side. It’s free, there are restrooms, and it’s a short walk to the bridge’s pedestrian lane.

- Safety: The pedestrian path is narrow. If you’re walking with kids, keep them close. The wind can be surprisingly strong up there, and the railing, while sturdy, feels low when you’re looking 130 feet down.

- Check the Weather: If the wind is gusting over 40 mph (which happens a lot in winter), the bridge can be closed to high-profile vehicles like campers. Check TripCheck.com before you head out.

What Most People Get Wrong

People often think this is the longest bridge on the coast. It’s not. That honor goes to the Astoria-Megler Bridge way up north. Others think it’s a "drawbridge." It definitely isn't. McCullough designed it with that massive 135-foot clearance specifically so ships could pass under without the bridge ever needing to open.

There's also a common misconception that the bridge is "failing."

Every time a chunk of concrete chips off, people panic on social media. The truth is, the bridge is inspected more than almost any other structure in the state. It’s old, sure. It’s "fracture critical" in some spots because of its design. But it’s not going anywhere. The effort to preserve it is massive because it’s not just a road; it’s a National Historic Landmark.

Actionable Insights for Your Trip

To truly appreciate the Yaquina Bay Bridge Oregon, do these three things:

- Walk the Span: Don't just drive. Park at the state park and walk to the center of the arch. Feel the vibration of the cars and look down at the fishing boats heading out to sea. It gives you a sense of scale you can't get from a car.

- Visit the Discovery Center: The Hatfield Marine Science Center is just south of the bridge. They have exhibits about the bay’s ecology, and from their parking lot, you get a great "side-profile" view of the bridge architecture.

- Stay for Sunset: The west side of the bridge faces the open ocean. If the clouds break, the orange light hits the concrete arches and makes them glow. It’s one of the best free shows on the Oregon Coast.

The bridge is more than just a commute. It’s a testament to a time when we built things to be beautiful as well as functional. Whether you’re a history buff, an architecture nerd, or just someone on a road trip looking for a good view, it’s worth pulling over. Just keep your eyes on the road until you find a parking spot—those lanes are narrower than they look.

Next Steps:

- Morning: Park at Yaquina Bay State Park and walk the northern pedestrian path for the best lighting.

- Afternoon: Drive across to the South Beach side and visit the Oregon Coast Aquarium; the bridge serves as a perfect backdrop for the walk between the two.

- Evening: Grab fish and chips at the Newport Bayfront and watch the bridge lights flicker on as the sun sets over the Pacific.