It’s late. You’re walking back to your dorm at West Virginia University, maybe scrolling through your phone or thinking about that mid-term you definitely didn't study enough for. Then you see it. A shadow moves near the trash cans by the Mountainlair or slips through the trees near the Evansdale residential complex. It’s not a stray dog. It’s a black bear.

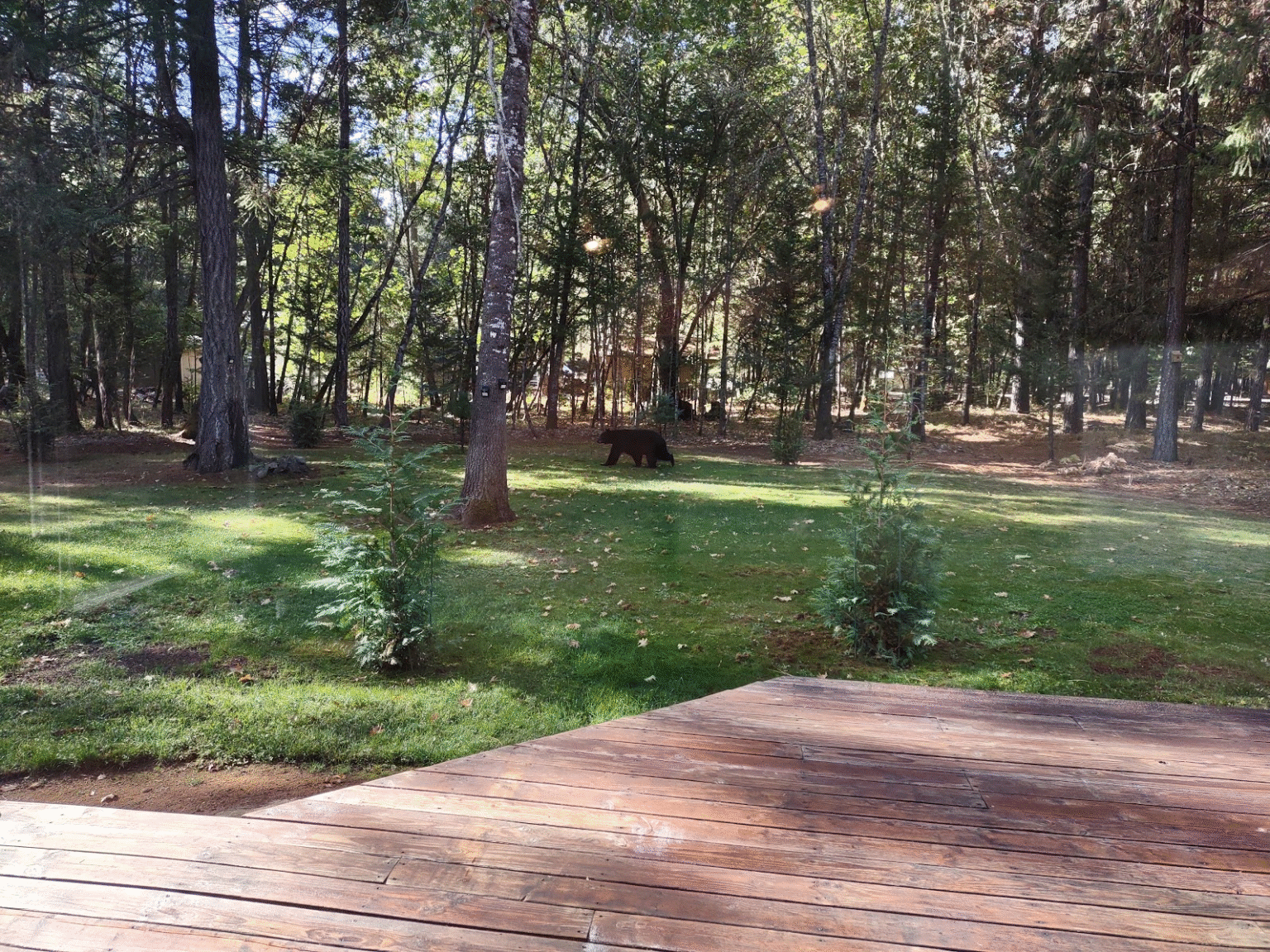

The WVU campus bear sighting is basically a rite of passage in Morgantown. Honestly, if you spend four years here and don't at least hear a story about a bear wandering near the Health Sciences center, did you even go to WVU? But lately, these encounters feel a bit different. They aren't just campfire stories; they are recorded on iPhones and blasted across TikTok within seconds. It's wild. People freak out, campus police send out alerts, and everyone starts wondering if the woods are taking back the university.

What’s actually going on with the WVU campus bear sighting?

West Virginia is bear country. That sounds like a cliché, but the biology backs it up. The West Virginia Division of Natural Resources (WVDNR) has been tracking a steady climb in black bear populations for years. Morgantown isn't some isolated concrete jungle; it's a city built into the side of hills, surrounded by deep hollows and dense hardwood forests.

When a WVU campus bear sighting hits the news, it’s usually because a young male bear is looking for a home. These "teenagers" get kicked out by their mothers in the late spring and early summer. They’re confused. They’re hungry. And honestly, they’re not very smart yet. They follow their noses, and in a college town, those noses lead straight to one thing: dumpster pizza.

It's weirdly fascinating. You have these animals that can weigh 300 pounds just chilling near a parking garage. Usually, they want nothing to do with us. They are terrified of people, or at least they should be. The problem starts when they realize that humans mean easy calories. A bear that finds a half-eaten pepperoni roll in a bin near High Street is a bear that’s going to come back tomorrow.

The geography of Morgantown makes it a bear highway

Look at a map of the campus. It’s not a contiguous block of buildings. You’ve got the Monongahela River on one side and steep, wooded ridges cutting right through the middle of the downtown and Evansdale campuses. The Arboretum is essentially a 91-acre buffet for a black bear.

Biologists like those at the WVDNR often point out that these wooded corridors act like highways. A bear can travel from the outskirts of Cheat Lake right into the heart of the university without ever having to cross too many open roads. They stay in the shadows. They move at night. Most of the time, we don't even know they're there. But every once in a while, a bear gets turned around or stuck in a spot where it can't hide, and that’s when the "bear on campus" tweets start flying.

The 2024 and 2025 incidents: A pattern emerges

In recent months, the frequency of these sightings has ticked up. We saw a particularly bold bear near the Canady Creative Arts Center not too long ago. Students were filming it from their balconies. It looked calm, almost bored, which is actually a bad sign. When a bear loses its fear of humans—a process called habituation—it becomes a "nuisance bear."

The University Police Department (UPD) usually handles these with a standard protocol: monitor the bear, keep students back, and wait for it to move on. They don't want to tranquilize it unless they absolutely have to. Why? Because drugging a bear is risky. A darted bear might run toward a busy road like University Avenue before the meds kick in, creating a massive safety hazard for drivers.

Misconceptions about black bear aggression

Everyone thinks a black bear is a grizzly. It’s not. Not even close. If you see a WVU campus bear sighting report, don't imagine a monster standing on its hind legs ready to roar. Most black bears in West Virginia are about the size of a large dog, and their first instinct is to bolt.

- They aren't looking to hunt humans.

- They are opportunistic scavengers.

- The most dangerous bear is a sow (mother) with cubs, but those are rarely the ones wandering through the middle of a campus.

- Most sightings involve solitary males looking for territory.

If you see one, the worst thing you can do is run. Running triggers a predatory chase instinct. It's better to just stand your ground, make yourself look big, and yell. Tell the bear to go away. Most of the time, it’ll be happy to oblige because you're loud and annoying.

The role of student behavior in bear encounters

Let's be real: college students aren't always great at waste management. Tailgating season is basically Christmas for a bear. Think about all that food left in trash cans after a home game at Milan Puskar Stadium. It’s a high-calorie goldmine.

The university has tried to mitigate this. You’ll notice more "bear-resistant" trash cans popping up around the outskirts of campus, especially near the residential halls on the hill. But these only work if people actually use them correctly. Leaving a bag of trash next to a full bin is just an invitation for a bear to come hang out.

There's also the "Disney effect." Some people see a bear and think it's cute. They want a selfie. They want to throw it a piece of food to see what happens. This is incredibly dangerous—not just for the person, but for the bear. A bear that gets fed is a bear that eventually gets euthanized because it becomes a threat to public safety. As the saying goes, "a fed bear is a dead bear."

What the experts say

The WVDNR spends a lot of time educating the public on this. They emphasize that West Virginia’s bear population is healthy—maybe too healthy for some urban areas. When we build more apartments and expand the university footprint, we are moving into their living rooms. We shouldn't be surprised when they show up in ours.

Wildlife biologists suggest that the "urban bear" phenomenon is here to stay. These bears are becoming incredibly savvy. They know the garbage pickup schedules. They know which neighborhoods have bird feeders. Bird feeders are a huge issue in the residential areas around WVU. A single bird feeder full of sunflower seeds has about the same caloric value as a massive steak dinner for a bear. It's easy math for them.

Practical steps if you encounter a bear on campus

If you find yourself face-to-face with a bear while walking to a late-night study session, don't panic. Panic leads to bad decisions.

First, give the bear space. Always leave it an escape route. If you corner a bear, it will feel threatened and might "bluff charge"—running at you and stopping short to scare you off. It’s terrifying, but usually, it’s just a warning. Back away slowly. Keep your eyes on the bear but don't stare it down in a way that feels like a challenge.

🔗 Read more: New York's 3rd Congressional District Explained: Why This Slice of Suburbia Defines American Politics

Report the sighting to UPD. They track these movements to see if a specific bear is becoming too comfortable around people. If a bear stays in one high-traffic area for too long, they might call in the DNR to relocate it to a more remote area like the Monongahela National Forest.

Protecting yourself and the wildlife

- Keep your distance. At least 50 yards is the rule of thumb, but more is better.

- Secure your trash. If you live off-campus in Sunnyside or near Evansdale, don't put your trash out until the morning of pickup.

- Don't leave pet food outside. Your dog’s kibble is a five-star meal for a black bear.

- Carry noise-makers. If you’re hiking in the nearby Arboretum, talk to your friends or play music. Bears don't like surprises.

The reality of the WVU campus bear sighting is that it’s a sign of a functioning ecosystem. It’s a reminder that even in a bustling university town, we are still guests in the natural world of the Appalachian Mountains.

Move your bird feeders inside if you've heard reports of bears in your neighborhood. Clean your outdoor grills after use, as the smell of grease can linger for days and attract wildlife from miles away. Most importantly, stay informed through the WVU Alert system. If there is a bear in a high-traffic area, the university is usually very quick to send out a text or email notification to keep everyone safe while the animal is moved along.