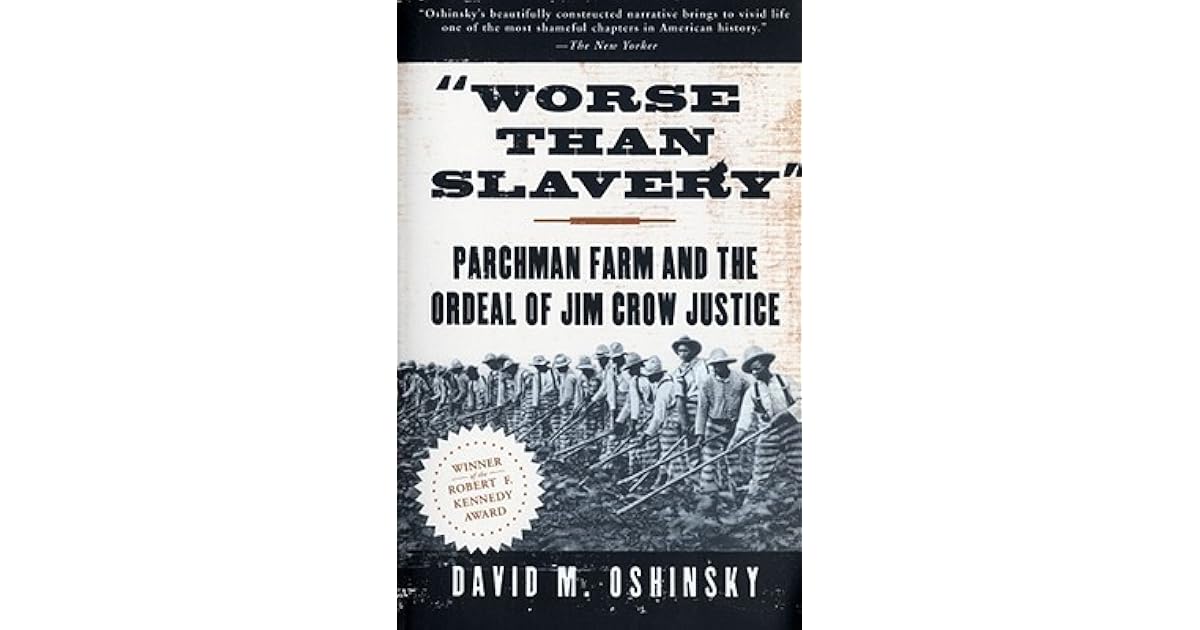

History is messy. It’s usually much worse than what we learned in those dry, state-issued textbooks back in high school. If you've ever picked up David Oshinsky’s Worse Than Slavery: Parchman Farm and the Ordeal of Jim Crow Justice, you know exactly what I mean. It’s a gut-punch. It basically shreds the idea that the Emancipation Proclamation was some magical "end" to the exploitation of Black labor in the American South.

Honestly, the title isn’t hyperbole. Oshinsky, a Pulitzer Prize-winning historian, argues that the post-Civil War system of convict leasing was actually more lethal than chattel slavery ever was. Think about that for a second. Under slavery, a human being was an "investment." Cruel? Absolutely. But there was a sick financial incentive to keep that person alive. Convict leasing? That was different. If a prisoner died from exhaustion or a beating in a coal mine, the state just sent a new one. They were disposable.

The Grim Reality of Parchman Farm

Parchman Farm is the centerpiece of the Worse Than Slavery book, and for good reason. It wasn't just a prison. It was a 20,000-acre plantation in the Mississippi Delta. After the Civil War, Southern states were broke. They had no labor force and a lot of destroyed infrastructure. So, they got creative in the worst way possible. They passed "Black Codes"—laws that made it a crime to be unemployed or to "loiter."

Suddenly, thousands of Black men were arrested for basically existing.

The state of Mississippi realized it could make a fortune by renting these men out to private companies. Railroads, mines, and planters paid the state a fee, and in exchange, they got a workforce they didn't have to pay, house well, or protect. It was a death sentence for many. Oshinsky digs into the records and shows that in some years, the mortality rate for these "convicts" was over 15 percent. That’s higher than almost any other labor system in modern history.

💡 You might also like: Why a Man Hits Girl for Bullying Incidents Go Viral and What They Reveal About Our Breaking Point

Why the Southern Economy Depended on the Chain Gang

You’ve probably seen the old movies with the striped jumpsuits and the sledgehammers. It looks like a cinematic trope. It wasn't. For decades, the entire infrastructure of the South—the roads you drive on, the tracks the trains run on—was built on the backs of men who were legally kidnapped by the state.

Mississippi didn't even have a centralized prison for a long time. Why build a building when you can just ship the prisoners to a farm? Parchman was designed to be the "ideal" prison because it turned a profit. It actually made the state money. Most prisons are a drain on the budget; Parchman was a cash cow.

Oshinsky describes the "trusty" system, which is honestly one of the most chilling parts of the whole story. The prison didn't hire many guards. Instead, they gave guns to certain inmates—the "trusties"—and told them to keep the others in line. It created a culture of paranoia and violence where the oppressed were forced to oppress each other just to survive another day.

What Most People Get Wrong About Jim Crow Justice

A lot of people think Jim Crow was just about separate water fountains and sitting at the back of the bus. It was so much deeper. It was a legal net. The Worse Than Slavery book highlights how the judicial system was weaponized to ensure a steady stream of labor.

📖 Related: Why are US flags at half staff today and who actually makes that call?

If a planter needed hands for the harvest, the local sheriff might just sweep through town and arrest every Black man on the street for "vagrancy." They’d be fined, they couldn't pay the fine, and then—boom—they’re on a chain gang heading to Parchman.

It was a cycle.

- Arrest for a minor or fabricated offense.

- An impossible fine or a long sentence at hard labor.

- Leasing the "criminal" to a private interest or the state farm.

- Using that labor to keep the state's taxes low for white citizens.

It’s a grim realization that the legal system wasn't broken; it was working exactly how it was designed to work. It was an economic engine fueled by injustice.

The Cultural Shadow of the Parchman Era

You can't talk about Mississippi or the Delta without talking about the Blues. And you can't talk about the Blues without talking about Parchman. Songs like "Parchman Farm Blues" by Bukka White aren't just catchy tunes; they are primary historical documents. They capture the despair of a place where "the sun goes down and you're still on your knees."

👉 See also: Elecciones en Honduras 2025: ¿Quién va ganando realmente según los últimos datos?

Oshinsky spends a good deal of time connecting these dots. He shows how the trauma of the convict leasing system leaked into the music, the literature, and the very soul of the South. It created a deep-seated distrust of the law that persists in many communities today. Why wouldn't it? When the law has spent a century acting as a labor broker, "Protect and Serve" sounds like a bad joke.

A Legacy That Refuses to Fade

Even after convict leasing was technically "abolished," the spirit of it remained. Parchman stayed a working farm well into the 20th century. The methods changed, but the goal—control and exploitation—remained remarkably consistent.

Oshinsky’s work is vital because it challenges the narrative of "progress." It forces us to look at how systems of power simply pivot when one method of exploitation becomes socially unacceptable. When the world said "no" to slavery, the South pivoted to convict leasing. When the world said "no" to that, they pivoted to the modern carceral state.

Actionable Insights for the History Buff or Student

If you're looking to actually engage with this history rather than just feeling bad about it, there are a few things you should do. Reading the Worse Than Slavery book is the first step, obviously, but don't stop there.

- Audit your local history: Most Southern states (and many Northern ones) had versions of convict leasing. Look up your state’s historical prison records. You might be surprised to see which local companies were built on leased labor.

- Support the Equal Justice Initiative: Bryan Stevenson’s organization does incredible work documenting these specific histories. Their "Legacy Museum" in Montgomery covers the evolution from slavery to mass incarceration in a way that perfectly complements Oshinsky’s writing.

- Listen to the Field Recordings: Seek out the Alan Lomax recordings from Parchman Farm. Hearing the actual work songs sung by the men in the fields provides a visceral connection that a book simply can't reach.

- Trace the Economics: Look into the history of major American corporations. Several household names today have roots in the industries that heavily utilized convict labor in the late 19th century.

Understanding the "why" behind the violence and the labor is the only way to make sense of the modern American legal landscape. It wasn't an accident. It was a business model.

To fully grasp the weight of this era, read the primary court transcripts from the late 1800s in Mississippi. You will see firsthand how quickly a "vagrancy" charge could strip a man of his freedom for years. This isn't just a "dark chapter" of history; it’s the foundation upon which much of the modern South was built. Start by mapping out the timeline of the 13th Amendment's "punishment clause" and how it was specifically exploited to create the Parchman system. Then, compare the labor output of Parchman during the 1920s to the state's overall GDP to see exactly how much Mississippi "earned" from this system.