Maps lie. Well, they don't exactly lie on purpose, but they're basically a mathematical compromise that messes with your head. If you grew up staring at a standard Mercator projection on a classroom wall, you probably think Greenland is the size of Africa and that the flight path from New York to London is a straight horizontal line across the Atlantic.

It isn't. Not even close.

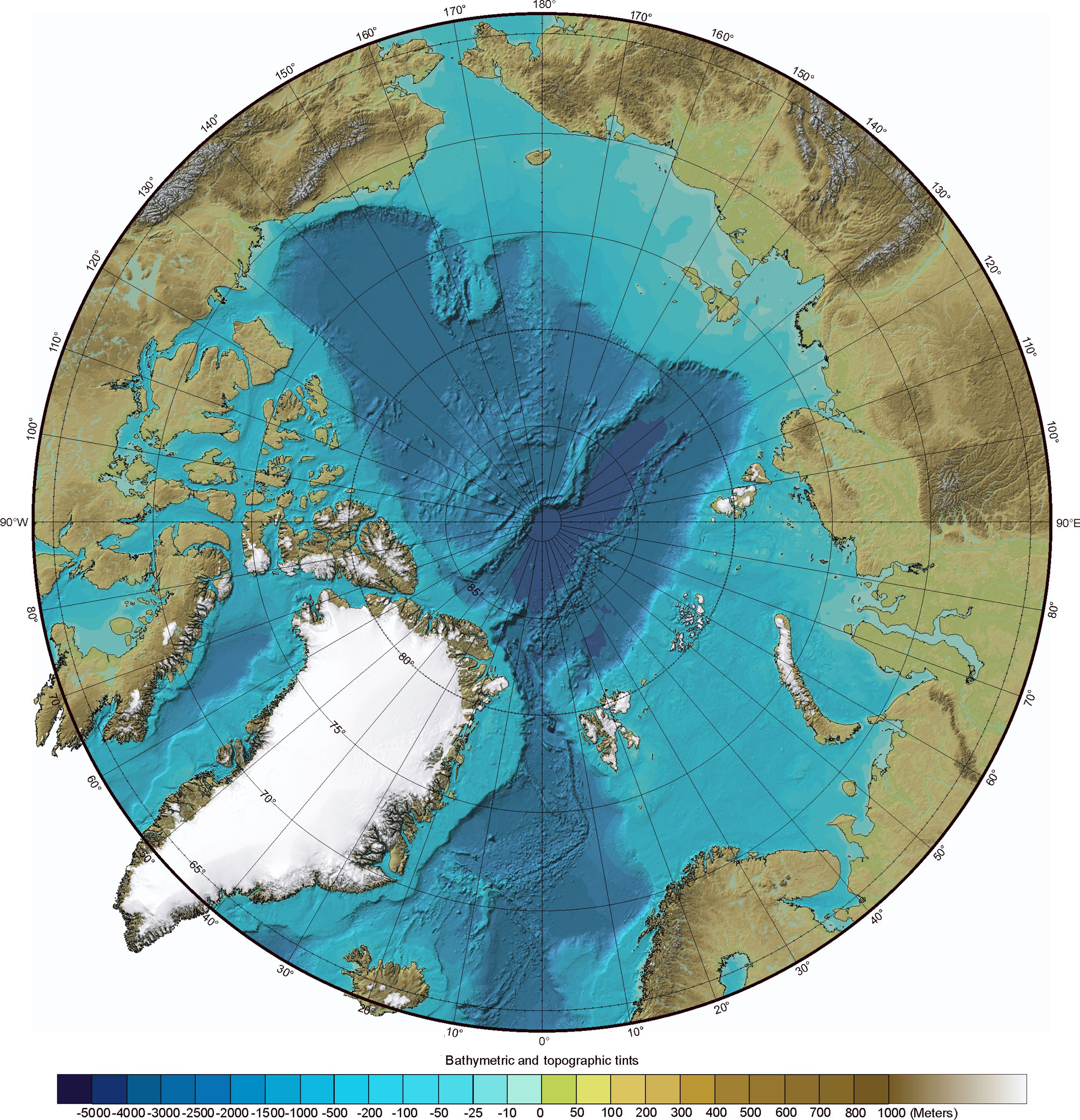

When you look at a world map from North Pole view—technically called a North Polar Azimuthal Equidistant projection—the entire planet suddenly looks like a weird, flat disk with the Arctic sitting right in the center. It’s the perspective used on the United Nations flag, and honestly, it's the only way to understand why the Arctic is becoming the most contested piece of real estate on the planet.

The Mercator Trap and Why Your Brain is Warped

We have to talk about Gerardus Mercator. Back in 1569, he designed a map for sailors. It was brilliant for navigation because a straight line on the map was a constant compass bearing. But to make that work on a flat piece of paper, he had to stretch the areas near the poles to infinity.

📖 Related: Mount Tambora Eruption Pictures: Why Real Photos Don't Exist (and What We Have Instead)

The result? You think South America is smaller than Europe. In reality, South America is nearly double the size.

When you pivot to a world map from North Pole perspective, that distortion gets flipped on its head. Suddenly, the "Top of the World" isn't some frozen wasteland at the edge of the frame. It's the hub. You see how closely Russia, Canada, and the United States actually huddle together. It makes the Cold War feel a lot more claustrophobic. During the 1950s, the DEW Line (Distant Early Warning) wasn't built looking "East" or "West" across the oceans; it was built looking straight up over the curve of the Earth because that's where the bombers would have come from.

It’s All About the Great Circles

Ever been on a flight from San Francisco to Paris and wondered why the little screen shows you flying over Greenland? You might think the pilot is lost. They aren't.

On a standard map, that looks like a massive detour. But on a world map from North Pole, you see the truth: that curved line is actually the shortest distance between two points on a sphere. These are "Great Circle" routes. If you take a string and stretch it across a physical globe, you'll see it.

The North Pole view makes these flight paths look like straight lines radiating from the center. It’s why Anchorage, Alaska, became the "Crossroads of the World" for cargo flights. If you look at the planet from the top down, Alaska is basically the mid-point between New York, Tokyo, and London.

The Geopolitical Mess at the Center of the Map

Climate change is turning the world map from North Pole from a cartographic curiosity into a high-stakes chessboard. Because the ice is melting, we're seeing the opening of the Northern Sea Route and the Northwest Passage.

Russia is obsessed with this. Like, seriously obsessed.

They have the world's largest fleet of nuclear icebreakers. If you look at a North Pole projection, you see why: Russia owns roughly half of the Arctic coastline. From their perspective, the Arctic isn't a barrier; it's a massive highway that could shave weeks off shipping times between Asia and Europe. While the rest of us are looking at the Suez Canal, the Kremlin is looking at the top of the map.

The U.S. has been a bit slower to the party. We only have two aging icebreakers, and only one of them actually works most of the time. But the "High North" is becoming a zone of massive military buildup. It’s not just about fish or oil—though there’s plenty of both—it’s about who controls the "Mediterranean of the North."

Why the UN Chose This Specific Map

Take a look at the United Nations flag. It's a world map from North Pole surrounded by olive branches.

Why? Because it’s the only map that doesn't put a single country at the "center" in a traditional sense. On a standard map, you have to choose which continent goes in the middle—usually Europe or the Americas—which pushes other countries to the "periphery."

By looking down from the North Pole, every continent (except Antarctica, which is relegated to the outer edge or omitted) radiates outward. It was meant to symbolize a world focused on a common center rather than divided by East and West. It’s sort of a "neutral" geography, even if it does make the Southern Hemisphere look like a giant, stretched-out ring.

The Problem With Polar Projections

Is it perfect? No.

Maps are basically a "pick your poison" situation. You can have accurate shapes, accurate areas, or accurate distances, but you can't have all three at once. On a world map from North Pole, the further you get from the center, the more things get distorted.

By the time you reach Australia or South America, the landmasses look like they’ve been put in a taffy puller. They get incredibly wide and flat. If you were trying to use this map to navigate around the Cape of Good Hope, you'd be in for a bad time.

How to Use This Perspective for Better Travel Planning

If you're a travel hacker or just someone who hates long flights, you need to start thinking in "Top Down" terms.

- Stop looking at the Atlantic as a barrier. If you're going from the West Coast of the U.S. to Europe, look for flights that transit through places like Iceland or even Fairbanks. These "over the top" routes are often faster and cheaper because they follow the actual geometry of the Earth.

- Check out Svalbard or Tromsø. When you see how accessible the high Arctic is on a polar map, these destinations feel less like "the end of the earth" and more like a bridge between continents.

- Understand the "Polar Pivot." Airlines like Finnair have built their entire business model on the North Pole view. They use Helsinki as a hub because, on a polar projection, it’s one of the most direct points between Europe and North Asia.

Real World Impact: The Arctic Council

The people who live and breathe this map are the members of the Arctic Council (Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden, and the U.S.). For them, the world map from North Pole isn't just a cool graphic; it's a matter of national security and environmental survival.

They have to deal with things like "black carbon" (soot from shipping) landing on the ice and accelerating the melt. They have to figure out who owns the Lomonosov Ridge—a massive underwater mountain range that Russia, Canada, and Denmark all claim is an extension of their continental shelf.

It’s basically a gold rush, but with more snow and more lawyers.

Your Map-Reading Action Plan

Next time you're looking at a news story about global shipping or international tensions, don't pull up a standard rectangular map. It will give you the wrong impression of distance.

Instead, find a digital globe or a polar projection. Look at the distance between Murmansk and the Bering Strait. Look at how close Greenland actually is to the Canadian Arctic Archipelago.

Once you see the world map from North Pole, you can't un-see it. You'll start to realize that we aren't separated by vast, insurmountable oceans as much as we are connected by a single, shrinking icy crown. The "Far North" isn't far at all. It's actually the center of everything.

Go get a physical globe. Seriously. Trace the path from your hometown to a city on the other side of the world with a piece of string. You'll probably find that the "straight" path goes much further North than you ever imagined. This is the simplest way to deprogram your brain from the distortions of 16th-century cartography.